Introduction to Intervals

4 Intervals Through Key Relationships

How to Listen

Taken out of context, intervals can seem as if they trick your ear: for example, a minor interval may “sound major,” and vice versa. This can usually be explained by music you have heard previously and absorbed unconsciously, so as an ear training student, it is important to understand the various contexts in which each interval can function. While your instincts may often be correct, you will still need to develop a method to double-check your first guess.

Seconds

While seconds are usually easy to identify when heard along, they can be confused for one another if heard after an interval that strongly implies a related key. Check your answer by building a scale around the interval. Major seconds will sound like the beginning of a scale (major or minor), but minor seconds will feel as if they “want to resolve.” The strongest resolving points for minor seconds are from fa to mi and ti to do in major keys, and le to sol in minor keys.

Sevenths

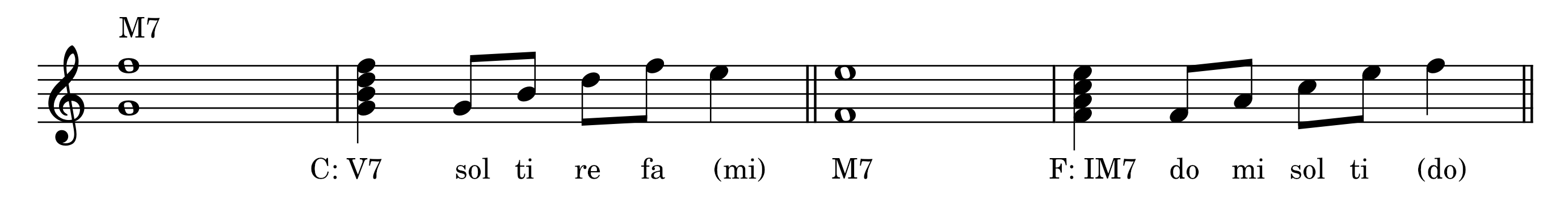

Sevenths only function as part of seventh chords. Check your interval by filling in the interval with a major triad that you build from the lowest pitch. If the top note sounds as if it should resolve downwards by a half-step (making a dominant chord), you have a minor seventh. If the top note resolves upwards by a half-step (creating a major seven chord), you have a major seventh.

Thirds

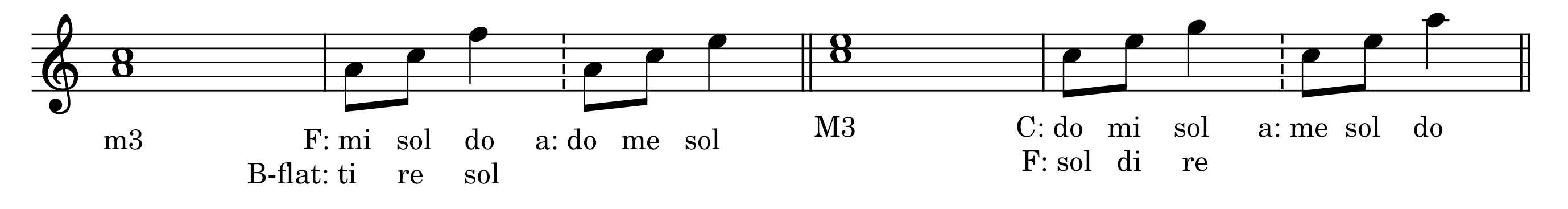

Thirds are one of the easiest interval classes to confuse. Thirds are the basis for both major and minor triads, so you may hear the top third from the opposite triad. For example, if you think you are hearing a minor “sound,” it can actually be the top third (mi to sol) of a major triad. The examples below demonstrate all the possibilities.

Sixths

Because sixths are inversions of thirds, they can cause confusion in many of the same ways. But due to the larger space between the two notes, there are even more ways in which you may hear this interval class. Always check your answer by completing the pattern; with sixths, it is possible to resolve the pattern upwards as well as downwards.

Perfect Fourths and Fifths

Perfect Fourths and Fifths should sound obviously different from all the other interval classes. However, learners easily confuse one with the other. The easiest way to check for a perfect fifth is to “fill in” the interval with a third to create a triad. For perfect fourths, check to see if the two notes sound like sol resolving upwards to do. However, follow do with a ti, and if the ti sounds as if it moves the tonality, it is probably fi. In this case, try your check for a perfect fifth interval.

Tritones

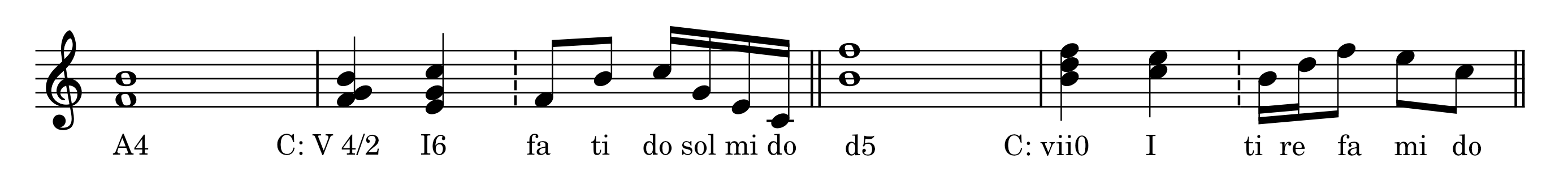

Tritones may end up being the easiest class for you to identify, even if they seem tricky at first. They have the same “crunchy” dissonance as seconds and sevenths, but they sit squarely between them. Most importantly, they should sound as if they “want to resolve.” You may hear them as resolving either inward or outward, but the result is the same. However, if you learn the tonal implications of the direction of the resolution (as illustrated below), you can improve your dominant identifications on harmonic dictation exercises (e.g. V7 vs. vii0).