Artistic Liberties

a) Deviations from standard fingering

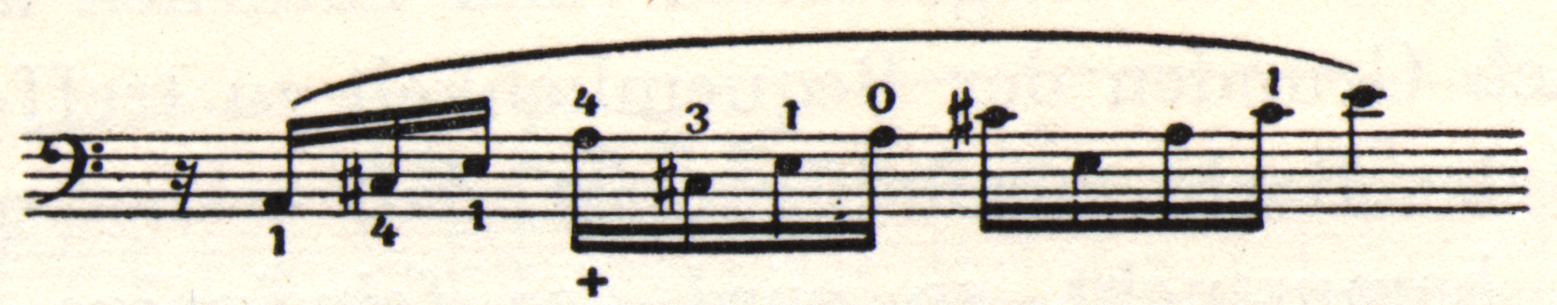

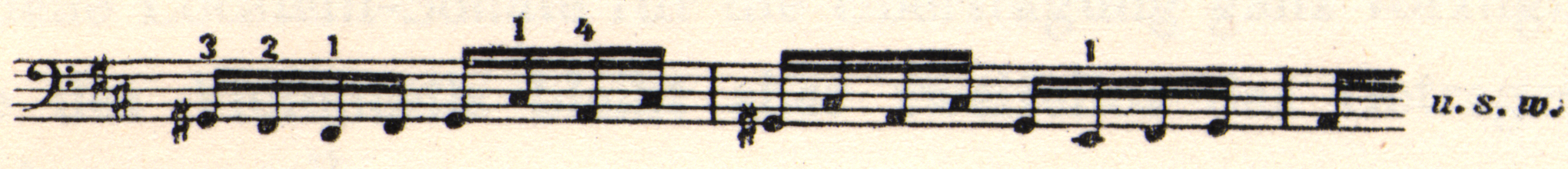

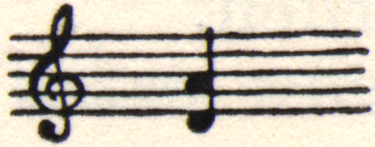

We can deviate from “correct” fingerings in various ways.[1] First, to smooth out mechanical unevenness:

(The fingering given here saves us from having to cross over two strings, which would be necessary if we took the A with an open string the first time.)

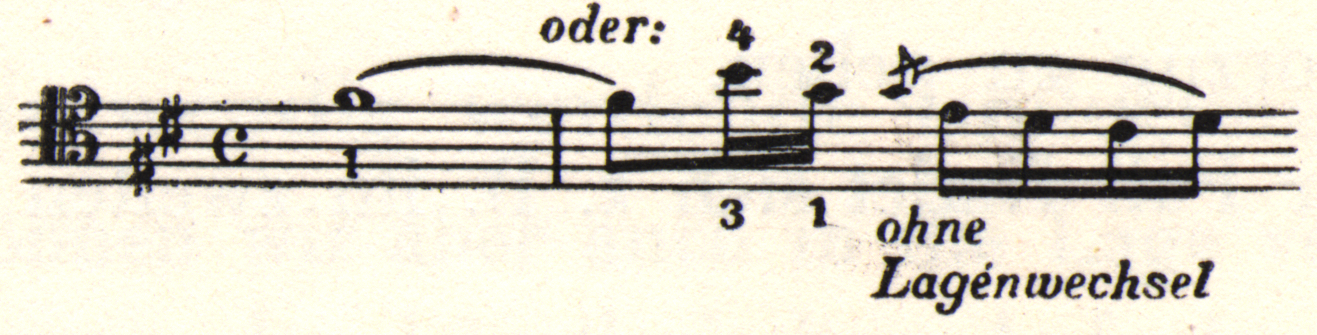

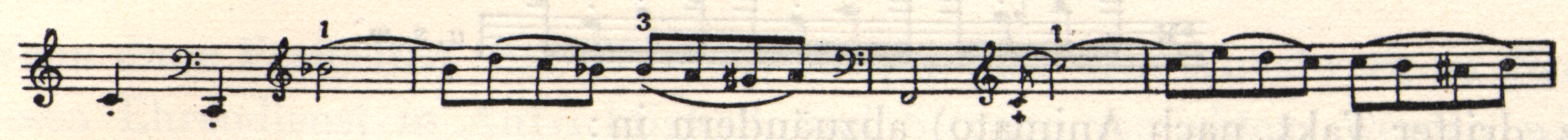

Further, to avoid an ugly position shift within a cantilena phrase, as in Bach’s Air in D major:[2]

Dvořák, Quintet, first movement:

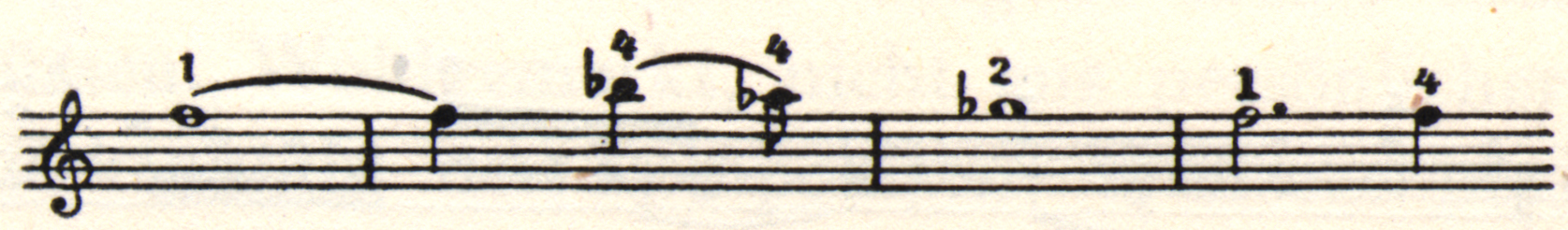

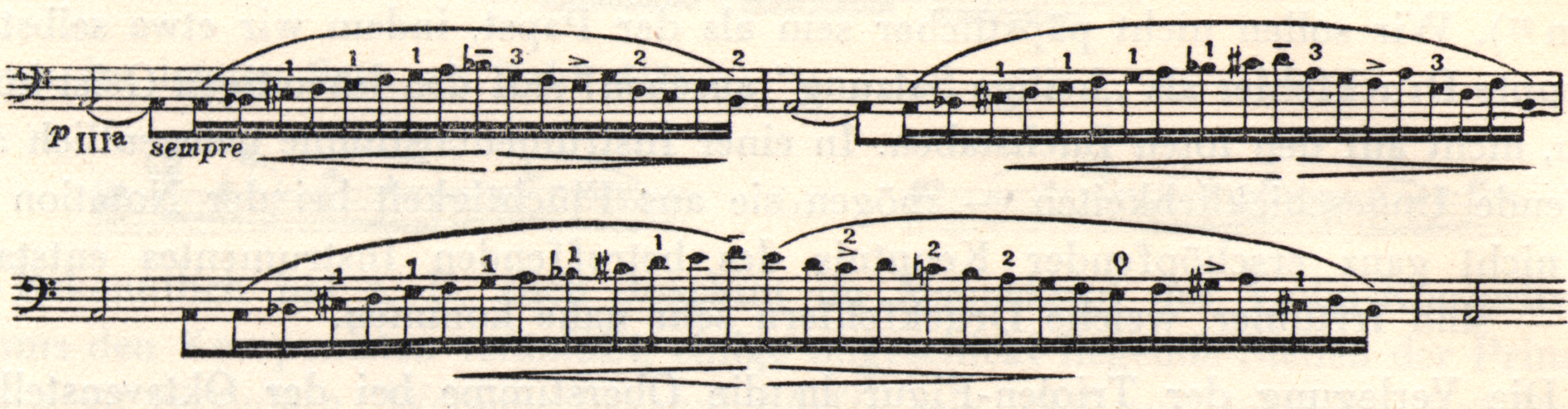

Or, to achieve a unified tone across registers, this passage from the Sarabande of Bach’s Suite in D minor:

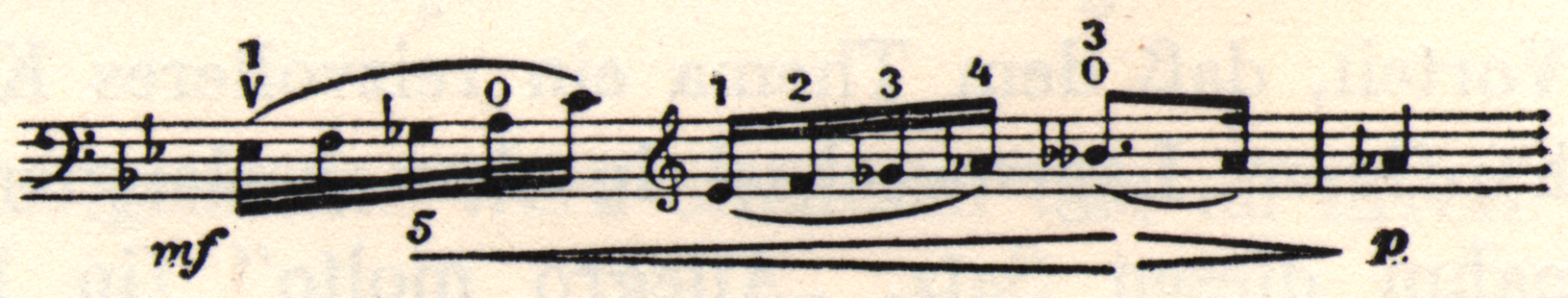

In the next example we use “moderated” fingering (above the staff) for similar reasons (Beethoven, Quartet Op. 59, first movement, main theme). The lower fingering can be recommended too, but definitely do not put a position shift between C and D!

For further examples of the deliberate choice of non-standard fingerings for artistic effect, consider the second theme of the first movement in the Schumann Concerto (see the essay “On Portamento”), as well as a passage from the Adagio of the Dvořák Concerto:

and finally one from Mendelssohn’s E-flat major String Quartet (Canzonetta, Più mosso, second part):

We should not shy away from choosing more difficult fingerings when artistic intentions are involved.

b) Choosing more difficult fingerings for artistically refined effects

We have said elsewhere in this book that the cellist is inclined to make the choice of fingering (and naturally also bowing and dynamics) mostly according to considerations of convenience. Even though every player fundamentally has the right to make playing as easy as possible, the serious artist will nevertheless seek more difficult solutions for certain musical-aesthetic reasons. The easiest way is not always the best and most beautiful! For the sake of making an interesting point, or for the sake of subtle dynamic shading, we ought to risk giving preference to a difficult, but artistically superior solution.

A classic example of this can be found in the second part of the first movement of the Locatelli Sonata:

I recommend this fingering not only to achieve the echo effect when the first motive repeats, but also for the uniform tone color it provides, which helps highlight the graceful figure. This creates a nice contrast with the continuation that follows on the A-string.

The same principle applies to what I mentioned earlier about the main theme in the final movement of Brahms’ F major Sonata, Op. 99. We can only fully realize the composer’s marking of “piano and mezza voce” by playing the theme in thumb position, where we can achieve the dynamic shading shown in the piano part—starting with p in the first two measures, then moving to pp from the third measure onward. The pp effect is only possible in thumb position on the D-string.

Beyond dynamics, thumb position offers another advantage: it gives the theme a more beautiful tone color than we could achieve with frequent position changes in the extended positions. Brahms played this movement, “Allegro molto” (in two!), very quickly, in contrast to the previous one, which he played at a more moderate tempo despite the “appassionato”.[3]

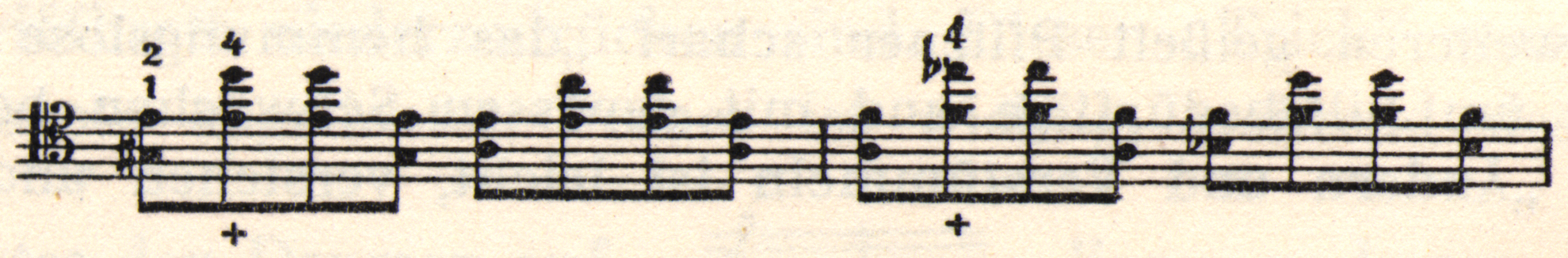

Here is the notation of the fingering:

The following measures, which are located at the end of the Volkmann Concerto, should be played “quasi improvisando.” We can also significantly enhance their effect by using the more difficult fingering, in which we play the entire passage exclusively on the G-string.

c) Necessary modifications

In exceptional cases, however, we may find ourselves in the position of having to make small technical modifications in favor of a more complete solution to the artistic task. Note that we do this not out of personal convenience, but solely in support of the composer’s intentions.

Not every composer knows the mechanics of individual instruments down to the smallest detail—unless they happen to be a virtuoso on the instrument in question—and are not always able to judge what can be executed well and what cannot. Sometimes, even very minor modifications (hardly worth mentioning as changes) can transform a figure that does not sound good (because it does not sit well under the hand) into one that sounds better. For example, in my experience of the following passage in the Saint-Saëns Concerto, the fifths—E to B and F to C—never sound quite pure. (See my analysis of the Saint-Saëns after letter C.)

This modification is recommended:

Of course, such modifications should neither change the harmonic structure nor the melodic line, nor adversely affect the voice-leading or emotional content. (If we think we need to make a complete rearrangement of a “suffering” work, then more drastic measures may be necessary.)

When we take liberties in the service of a work of art, and we perform this honorary service both sincerely and strictly, we can hardly go wrong. Artistic conscience will surely guide the good musician and protect them from violating overly subjective demands).[4] We should not become more papal than the Pope by viewing our own careless printing errors as “sacred text”! It depends on the living spirit, not the dead letter of the law. In an instrumental voice, inadvertent inaccuracies may occasionally occur due to carelessness in notation or from not fully understanding the characteristics of the instrument in question—these are errors that come very close to misprints.

The relocation up an octave of a triplet figure in the last movement of Dvořák’s Concerto also falls under this rubric. My suggestion was met with the approval of the Bohemian master.

That composers are receptive to to suggestions from qualified performers may be mentioned here with reference to the d’Albert Concerto. Here, the composer readily agreed to change (among other things) this passage from the first movement (third measure after Animato):

to this:

Similarly, in the last movement, from measure 42, he agreed to change this:

to this:

It is well known, for example, that Joachim also persuaded Brahms to alter some awkwardly placed passages in the solo part of the manuscript of his Violin Concerto. Less well known is that on Joachim’s advice, Brahms re-orchestrated the beginning of the first movement of the B-flat major Sextet. In the first version, all six instruments began at once.

d) Use of auxiliary notes

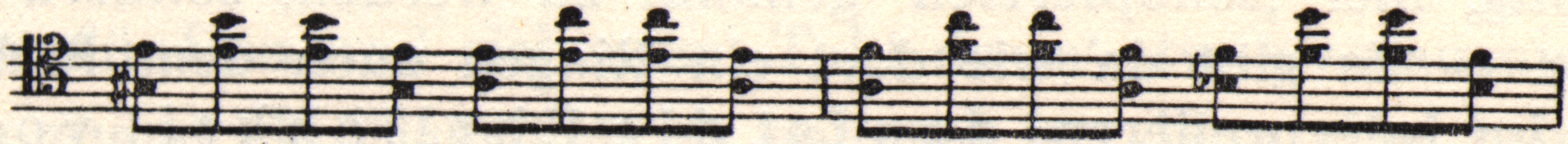

The A major episode in No. 3 of Schumann’s Pieces in Folk Style is among the most unidiomatic passages in our literature. The fingerings indicated speak for themselves. At best, the last two measure could be played on the A-string, but this would by no means simply things:

If we use the fingering shown here, we should mark the following: we can achieve greater security if we slightly anticipate the A by arpeggiating it in the sixth (A and F-sharp) in the fifth and seventh measures. We can start the note on the natural harmonic, but when we play the F-sharp, we should put the finger that is on the A down on the fingerboard. The “trick” here is notated as a grace note. Furthermore, it is important to leave the thumb on these notes in the seventh, eighth, and tenth measures:

When taking the the sixth (C-sharp and A in the penultimate measure), however, the hand must move up a major second, through which we can get to the new position (thumb on E and B) correctly. This means that the next double stop (C-sharp and E) can be accomplished.

That composers not only tolerate auxiliary notes in some cases, but actually prescribe them themselves can be seen in the following cases:

1. In the first movement of the Schumann concerto, the composer can only have provided the C grace note to make it easier to get to the high C (after the preceding low F!), since the grace note is missing both in previous instances of the figure and also where it occurs again after the development section.

2. Regarding the last movement of Beethoven’s Sonata in A major, we must ask ourselves why the octave grace note is missing in the return of the theme later in the movement?… Why shouldn’t Beethoven, in view of the difficulty to cellists of landing on the high E, have made a concession to the player to facilitate their job?

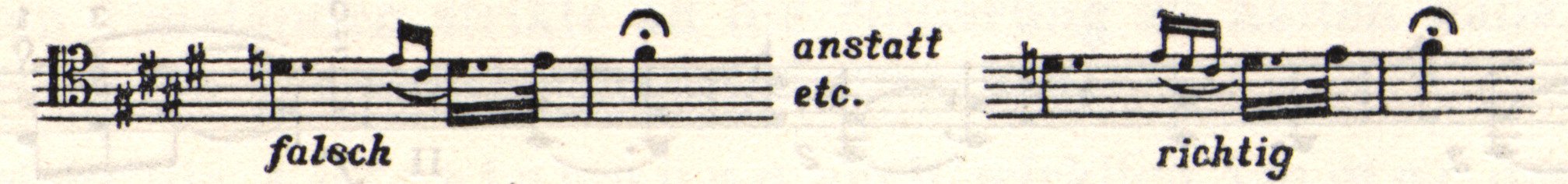

The absence of the grace note when this figure returns in the recapitulation supports this hypothesis. It’s possible that the composer could have forgotten to put it there. But we know that Beethoven mentions, among other things, several other printing errors in the same sonata in his correspondence with Breitkopf and Härtel (errors that unfortunately have not been corrected to this day). These include the following:[5]

Therefore, we should not assume that he would have stayed silent over a major printing error like that.[6] The assumption that the grace note E is a concession to easier playability is therefore probably correct. If we were to reject this view, we would then have to add the grace note at the return of the second theme in the recapitulation!

If, hypothetically, Beethoven had not written this grace note and some player added it as an “auxiliary note,” imagine the outcry this would raise among the guardians of musical virtue!

3. A similar case is found in Strauss’s Don Quixote (cf. my analysis of Variation VI). I would therefore like to point out today that the short grace notes in question, while added by me, were sanctioned by the composer.

- Becker uses the adjective schulgerechten, literally "school-correct." ↵

- Ohne Lagenwechsel = without a position shift ↵

- Becker's note: I often had the opportunity to play the aforementioned work with Brahms himself, both in private and in public." ↵

- Becker's note: "On the occasion of the Krefeld Music Festival in Krefeld June 13, 1927, Hans Pfitzner gave a very noteworthy, interesting lecture on the theme "The Protection of Artistic Creation." He also debated the question of whether interpreters should adhere strictly to the notation of the work entrusted to us, or whether we should allow ourselves certain liberties under all circumstances. From his lecture, I quote the following matters for consideration: "Does the notation also really always correspond to the how the creator imagined it? May the interpreter improve it, or supplement it? Where does that leave the question of responsibility? — We know, for example, that Richard Wagner changed the instrumentation of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony in his performance, but also know that this was a work of love, of deepest empathy with another work of art, a service to it, the perfection of an admittedly incomplete sonic picture, in short, an interpretation that fully served the meaning of the work and whose effect has been proven to be historically favorable to Beethoven's work. He did not change for change’s sake, but for love for the work. Richard Wagner did not need anyone to praise him for “perfecting” anything: he acted a servant of the work. — It is evident how much more one can achieve in creating than in interpreting; that is honesty in itself." Pfitzner further lashes out sharply against "uninhibited tinkering, even when it concerns works that are not in need of help or afflicted with any weaknesses" and says: "Changing and mutilating is easy, understanding and perfect interpretation are difficult." From Pfitzner's beautiful, commendable words it emerges that there are cases where the interpreter may be compelled to intervene, but that his deeply rooted sense of responsibility toward the work and its creator must be so strongly developed that an intervention is as good as excluded." ↵

- Anstatt = instead of, falsch = wrong, richtig = correct ↵

- Becker's note: "Cf. Kalischer, Beethoven's Letters, volume 2, letter no. 431. ↵