Compound Bowing Techniques

True mastery of mechanics shows itself less in the ability to execute certain techniques with the highest virtuosity—whether brilliant feats for the left hand or those of the bow—and more in the ability to make the entire field of cello technique serve artistic purposes. The various bow techniques should only be regarded as means of expression, and their application must always follow a meaningful musical plan. While individual stroke types create nuances (see the section on off-the-string strokes), combining different types of bowstrokes offers unlimited possibilities for musical shaping and expression. From the wealth of examples in the literature, here are some typical cases.

1. Legato and détaché

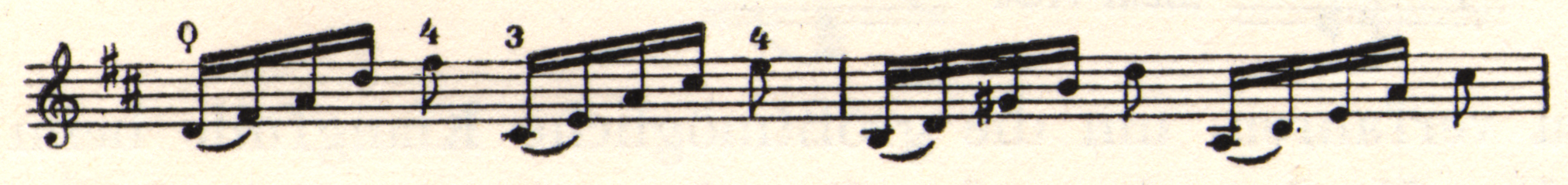

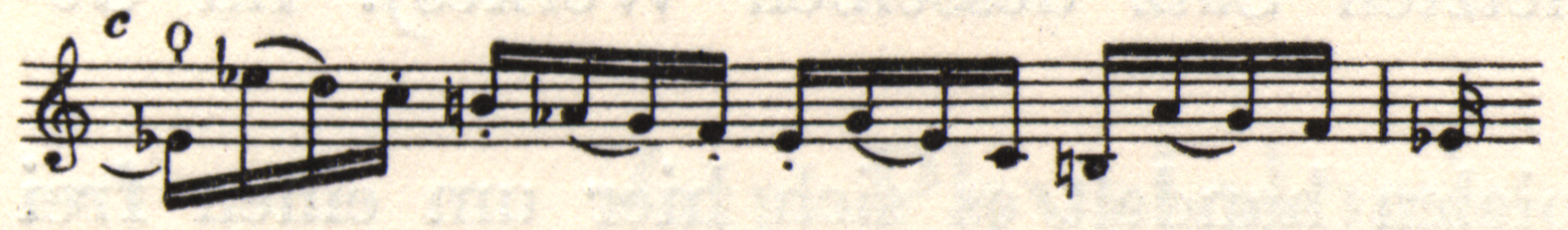

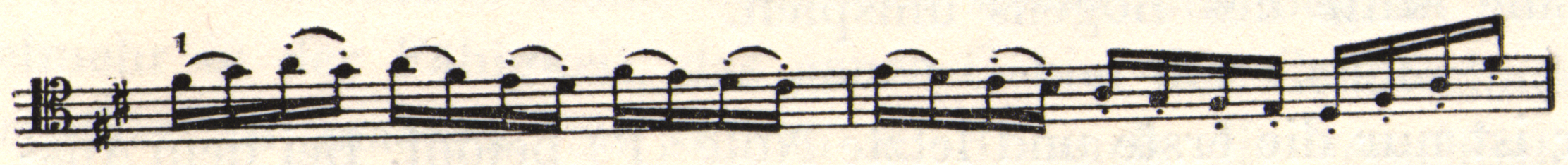

From Haydn’s Concerto in D major:

This goes best if we start the slurred notes in the middle of the bow, then move towards the middle for the détaché notes. (See the analysis of the Haydn Concerto in Part II of this book.)

From the first movement of d’Albert’s Concerto:[1]

Play this entire passage close to the fingerboard with soft, “elastic” bowing, connecting the detached notes well. Use plenty of upper arm movement and a sotto voce character.

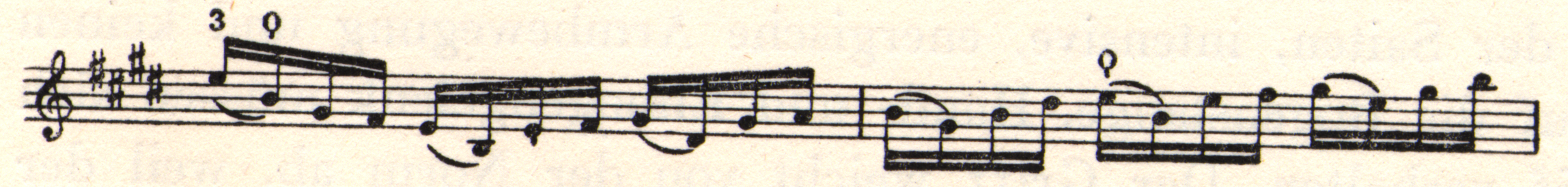

From the first movement of Becker’s Concerto in A major:[2]

Use a very energetic, brilliant détaché with broad strokes in the middle of the bow. Play the string crossings rhythmically and precisely.

2. Legato and martelé

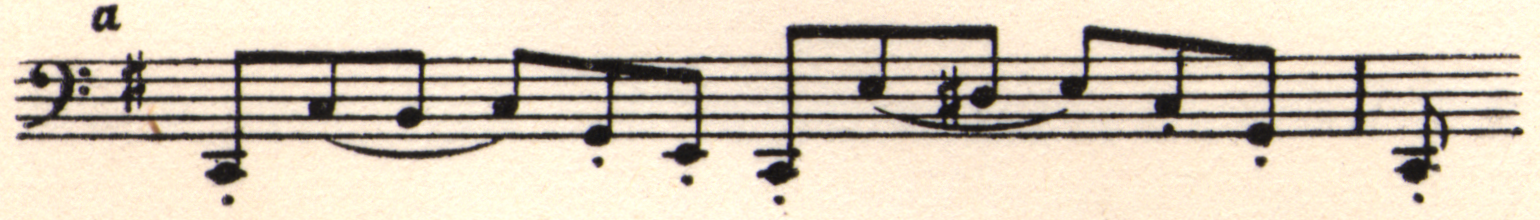

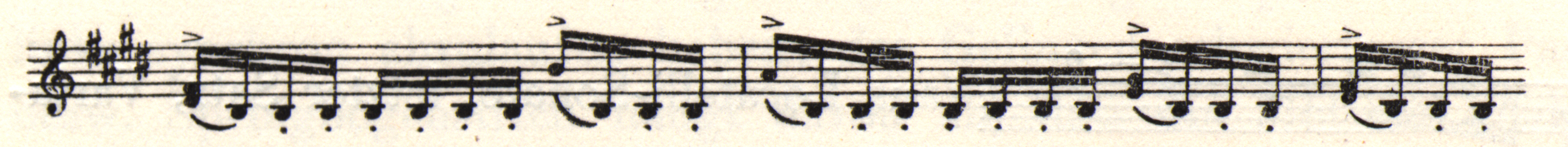

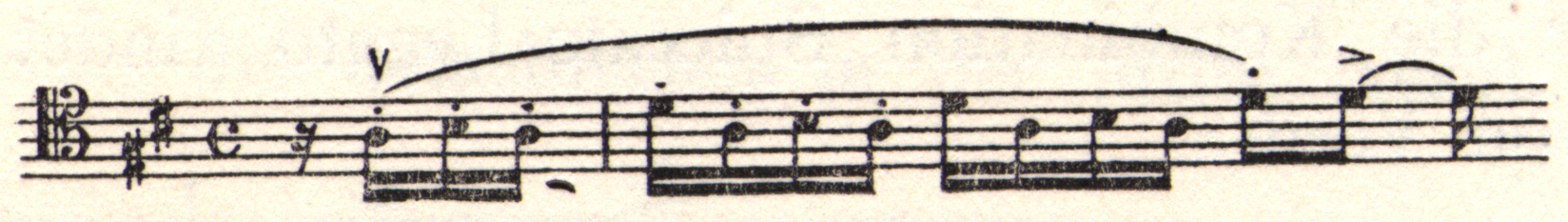

In various passages from Romberg’s concertos:

(a)

Play very energetically and rhythmically. In particular, do not neglect the slurred notes. Keep the other notes short and articulate! Always play the martelé strokes below the middle of the bow.

(b)

The difficulty here is that the up-bow on C-sharp must be executed with the same force as the down-bow stroke on F-sharp in the previous group of notes, although because of down-bow on the D-string that immediately follows, the hand has to be placed in a stretched position.

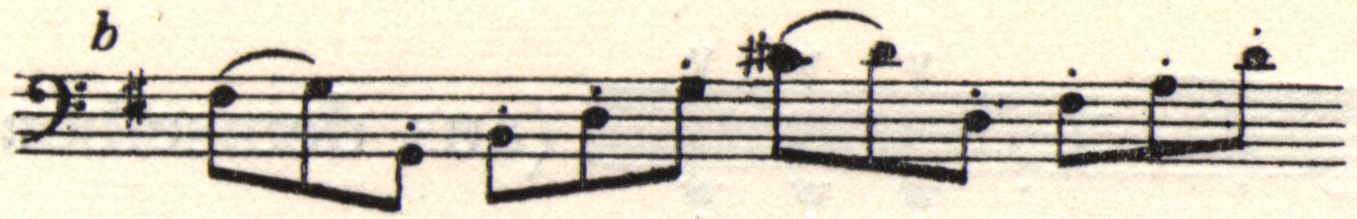

(c)

Here, pay attention to accenting the first note of each group of sixteenth notes. Use more bow on the accented notes and less on the unaccented ones. Keep the bow in and around the middle.

(d)

Here, only the first and last notes are accented. When preparing to accent the last note (F), take care not to accent the preceding G.

3. Legato and spiccato

From the last movement of the Valentini Sonata:

We must take two things into account here: first, that the appearance of the melodic notes should not disrupt the rhythmic continuity of the pedal point (the sixteenth notes on B). Second, that during the legato strokes, the part of the bow we use must not move too far away from the place that is most favorable for spiccato, i.e. the balance point.

Another instructive example of the spiccato-legato combination can be found in the first movement of Verdi’s String Quartet:

Here, the spiccato sixteenth notes should be played very lightly and fleetingly around the middle of the bow. However, since the motive in the second half of both measures requires a longer bowstroke, we must bring the bow back to the frog in the air after the last sixteenth note (E). We can only do this rhythmically if we use the grip change technique repeatedly. The hand and fingers can then save the arm quite a bit of the distance it has to travel.

4. Legato and ricochet

From the last movement of the Valentini Sonata:

In this example, we must play the ricochet notes very actively. It is not just a matter of letting the bow bounce, but also involves a “pushing” movement.

From the Tempo di Gavotta movement of the same work:

This example also contains a kind of highly active ricochet.

From the last movement of the same work:

Unlike the two preceding examples, this example utilizes a “freely-falling” ricochet.

5. Legato—ricochet—spiccato

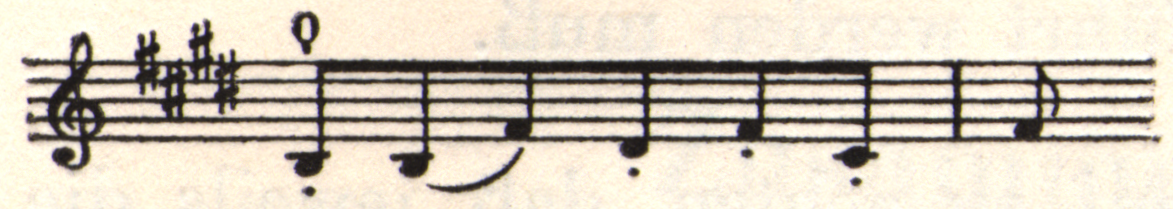

From the Locatelli Sonata, third movement, variation IV:

The first measure of this passage is similar to the first two examples in the “legato and ricochet” section. The second measure contains a slow, ricochet-like spiccato.

6. Legato—détaché—spiccato

The passage should be played with a delicate, gentle tone, beginning hesitantly with a soft legato or détaché stroke, followed by a light, dancing spiccato. Make up for any delay in tempo.

7. Staccato— martelé— full bow stroke

From the beginning of the first movement of the Locatelli Sonata:

Here, the tempo should be taken moderately fast; M.M. ♩ = 108, and the staccato played with great evenness because the grace inherent in the movement is easily lost at a faster tempo. The subsequent martelé eighth note should be played rhythmically and decisively!

8. Martelé—ricochet

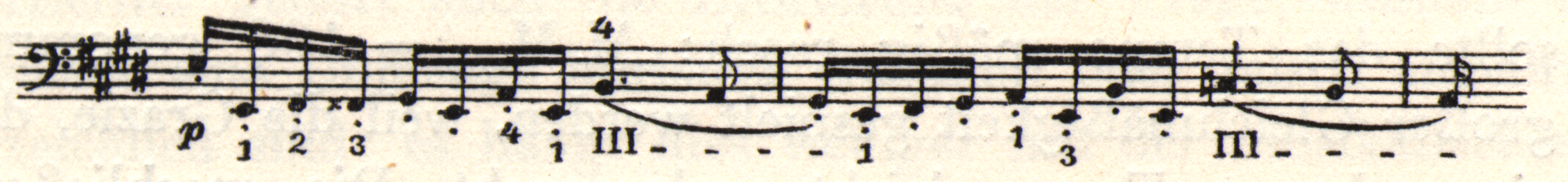

From Hugo Becker’s Concerto in A major:

Here again is an active ricochet bowstroke. Execution requires significant effort in the lower third of the bow. Use quite a bit of bow hair in contact with the string. The first note of each triplet should use as much bow as the following two together.

From the last movement of the Valentini Sonata:

To ensure that as much bow as possible is available for the up-bow ricochet notes, play the first eighth note martelé, using the whole bow.