Guidelines for a Meaningful and Comprehensive Interpretation of the Cello Obbligato in Richard Strauss’s Don Quixote

Knowledge of the poetic material as well as the score should be the obvious prerequisite when studying the Don Quixote “role”! — Unfortunately, this is not always the case — hence the frequent failure even of skilled cellists to solve this not-easy task.

I know of no piece in the cello repertoire that demands more imagination and acting ability from the player — the interpreter of the “Knight of the Woeful Countenance.”

A fairly extensive, beautiful tone and reliable left-hand technique (who wouldn’t claim to have these!) are still far from sufficient to fully solve the task at hand. We need more than that! It is not only a matter of flawless rhythmic and dynamic performance, but one must attempt to do justice to the various moods and situations of this Romantic piece. To achieve this, we can use portamento and vibrato with endless flexibility, which—combined with subtle tempo changes—give us the tools to create a truly vivid, three-dimensional performance.

From a psychological perspective, Don Quixote is a poetic symbol. He represents the romantic dreamer, the hopeless idealist who sees the world only through the lens of his own imagination and stubbornly keeps believing in his fantasy world no matter how many times reality defeats him.

Cervantes brings this idea to life through his knight from La Mancha. Don Quixote’s imagination, fired up by too much bad literature, leads him to become a wandering adventurer. His delusion that he’s destined for greatness—to help the downtrodden and fight evil—gets him into all sorts of dangerous situations that always end in tragicomic disaster.

However, it would be a mistake for the performer to see our hero only as a comic figure, to find greatness and nobility only in how he looks and what he attempts. The feelings that drive this deluded character to his fantastical deeds are always noble and chivalrous ones. Goodness, courage, and gallantry define his character, undiminished by all his eccentricities. Despite all his bitter experiences, Don Quixote holds fast to his supposedly noble mission. That is the morally beautiful aspect of him.

In this strange delusion, he keeps throwing himself into new adventures until finally he experiences an awakening that pulls him out of his dreams and lets him become a normal person again. In this way, he peacefully ends his days…

You can easily imagine how rich and varied a performance of the Knight of the Woeful Countenance and his adventures needs to be, given the extraordinary nature of this story.

Only a genius like Strauss could succeed in giving this imaginative, richly pictorial poetry an equivalent expression in the language of music. How intense and vivid the figures and events of this tragicomedy appear to us, how striking is the unusual inner life of our hero depicted in the score! To make such complicated psychological processes understandable, one certainly needs a rich arsenal of artistic and technical means. The representative of the title role should be a wonderfully original tone-poet, a congenial assistant to the composer.

Before we go into details, let me point out some general guidelines: the expressive means available to the interpreter must be used in the most economical and refined way. The interpreter must not use vibrato or portamento thoughtlessly and indiscriminately—rather, it’s about clearly distinguishing the feelings of tenderness like longing, melancholy, lovability and gallantry, from those of passion and pain, as well as from those of energy like fighting spirit, indignation, anger and hatred. Accordingly, bowings should never be chosen for reasons of convenience. The designations added by the editor (up-bow and down-bow symbols) should not override the composer’s intentions regarding phrasing—on the contrary, they should support and bring them to fruition (see the essay “On the Meaning of Slurs in String Literature”).

Now let us turn to the score.

The supplementary note on the title page: “Fantastical Variations on a Theme of Knightly Character” already presents a program!

The theme:

This depicts the knight lost in thought in the traditions of old Spanish chivalry and feeling. In its first four measures the theme expresses pride and determination, and should therefore be presented with a certain “grandezza”; the following measures at rehearsal 13, however, depict the feelings of knightly gallantry and thus require the expression of amiable grace.

Variation I. On his warhorse “Rocinante,” Don Quixote trots along leisurely, accompanied by his squire Sancho Panza, hoping along the way to find tasks whose solution will bring him fame and honor and the gracious thanks of his beloved Dulcinea, the lady of his heart.

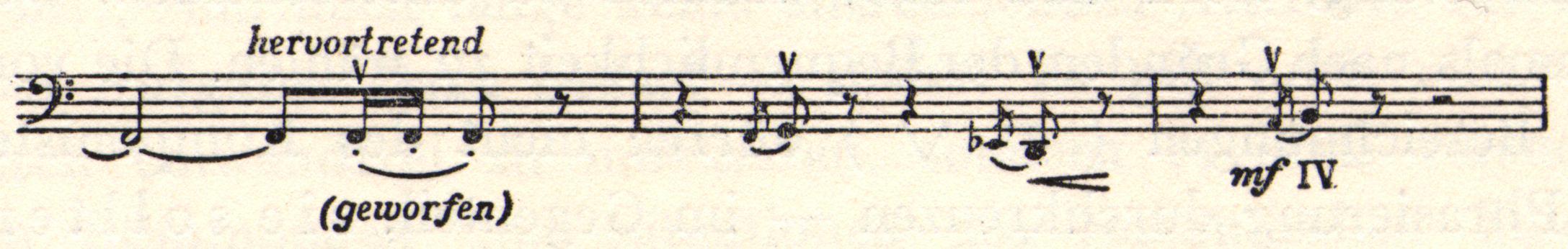

It’s difficult to keep the old nag at an even trot—he often stumbles or staggers (the note groups enclosed in dotted brackets represent windmills) as becomes apparent. He spurs him on again (p. 28, fourth measure; p. 29, first measure), charges with lowered lance at the imaginary opponent:

and immediately lies with twisted limbs on the ground (held low F). Consciousness returns (p. 31); wearily he rises…

…and laments loudly, in longing thoughts of Dulcinea,

in whose honor and praise—as he imagines—he tests his weapons.

In Variation II three solo cellos take over the role of Don Quixote. Conversations between Don Quixote and Sancho Panza.

Variation III. Questions, demands and trivial sayings of Sancho are followed by instructions, appeasements and promises from the knight. The obbligato cello voice is mostly doubled here with other instruments, so further notes are unnecessary.

Variation IV. Don Quixote sets his Rocinante in motion again and encounters a pilgrimage, which he believes to be evil robbers attacking. A skirmish ensues, in which our hero again gets the worst of it.

A scuffle ensues, in which our hero again comes off worse and is knocked to the ground (held low D, p. 59). After some time, his spirits revive again; he pulls himself together and sets off on new deeds.

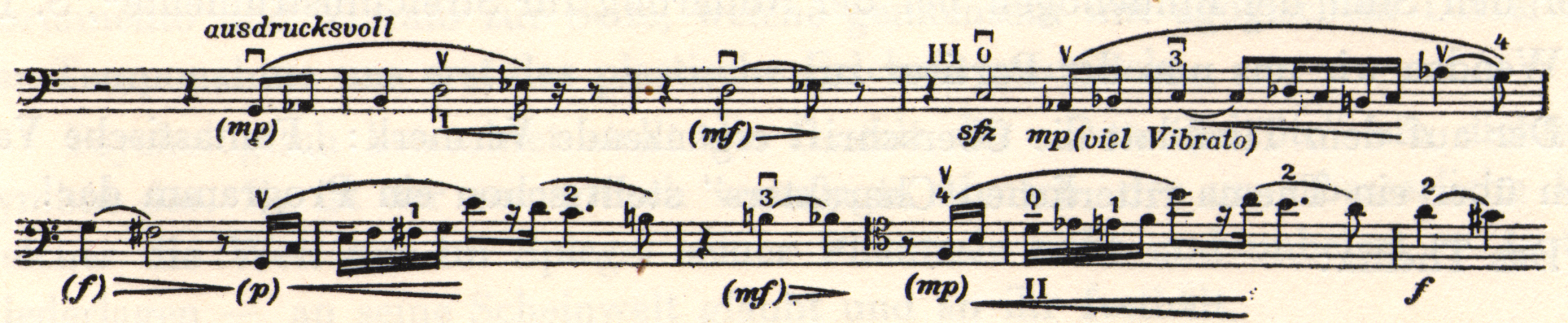

Variation V. The depiction of the nocturnal “vigil of arms,” which Don Quixote “faithfully observes according to the custom of knights errant,” places the greatest demands on the interpreter of the title role. In this variation, more than in any other, it becomes clear what kind of artist the performer truly is and how well he understands how to use his technical skills to bring these complex psychological processes to life as musical imagery for the listener. He sends sighs, pleas, and protestations into the distance to Dulcinea, the lady of his heart.

The interpreter will do well to treat these soliloquies—sometimes reflectively whispered softly into his beard, sometimes suddenly swelling to loud calls and confessions—strictly according to the meaning of the themes and to shape them based on this understanding. The rest can be seen from the supplementary notation of the violoncello part. It should be particularly noted that in the first measure, at the interval between B-flat and F, no glissando should be heard. You have to stretch it!

Variation VI. Sancho tells his knight that an ugly peasant girl passing by is his adored Dulcinea. Don Quixote indignantly rejects this insinuation.

The effective portrayal of indignation succeeds through precise observance of the bow strokes and fingerings. The added short grace notes, before D and E respectively, through which the high notes can be brought out with particular force, significantly enhance the expression of outrage.

Variation VII depicts the supposed air journey on the magical wooden horse “Clavilenno.” The solo cello has no role in this variation.

Variation VIII. The boat ride: Don Quixote embarks with Sancho in a rudderless boat on the Ebro River. The current drives it toward a mill wheel, and it capsizes. With great effort, the miller’s servants manage to rescue the knight and his squire from what Don Quixote originally took to be devils, from certain death by drowning.

The pizzicatos in the solo cello (and other string quintet parts) at the end of the variation can be interpreted as the dripping of water-soaked clothes. Perhaps also as differences of opinion between knight and squire. The former must be played very strongly in the solo cello; the performer achieves this when he plucks the string with his snapping finger far down, at the end of the fingerboard, with the thumb resting firmly against the outer edge of the hand as a support point. The unsuccessful striking of the string that easily occurs with strong pizzicato is thereby completely avoided.

Variation IX. In this variation, which depicts an attack by two peaceful monks whom Don Quixote takes for evil sorcerers, the solo violoncello plays no part.

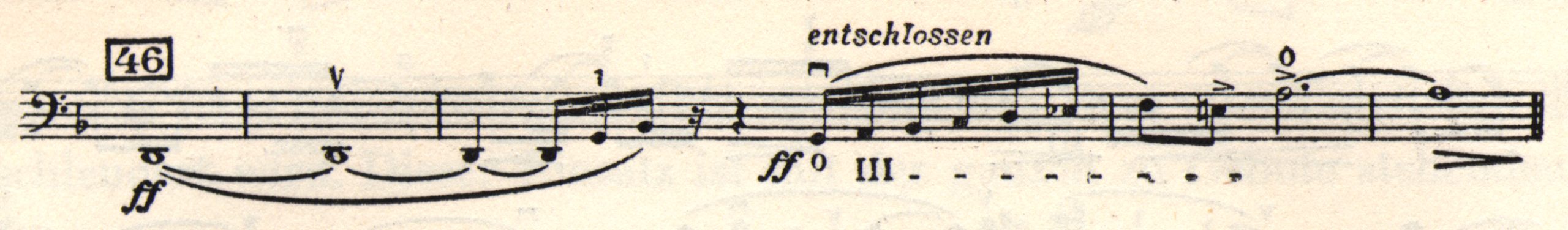

Variation X. The battle with the “Knight of the White Moon” defeats Don Quixote. As a result of the previously agreed arrangement, he must renounce further adventures as the vanquished party.

The high F in the solo cello (rehearsal 68) represents the lance thrust that lifts Don Quixote from his saddle hurls him to the ground. This passage must be executed with all available force.

The measures starting from rehearsal 69 depict the “Lamento” which Don Quixote now intones over his defeat and its consequences:

Sadly, he journeys homeward. Abundant use of vibrato and portamento is appropriate here to restore the lamenting, tearful character.

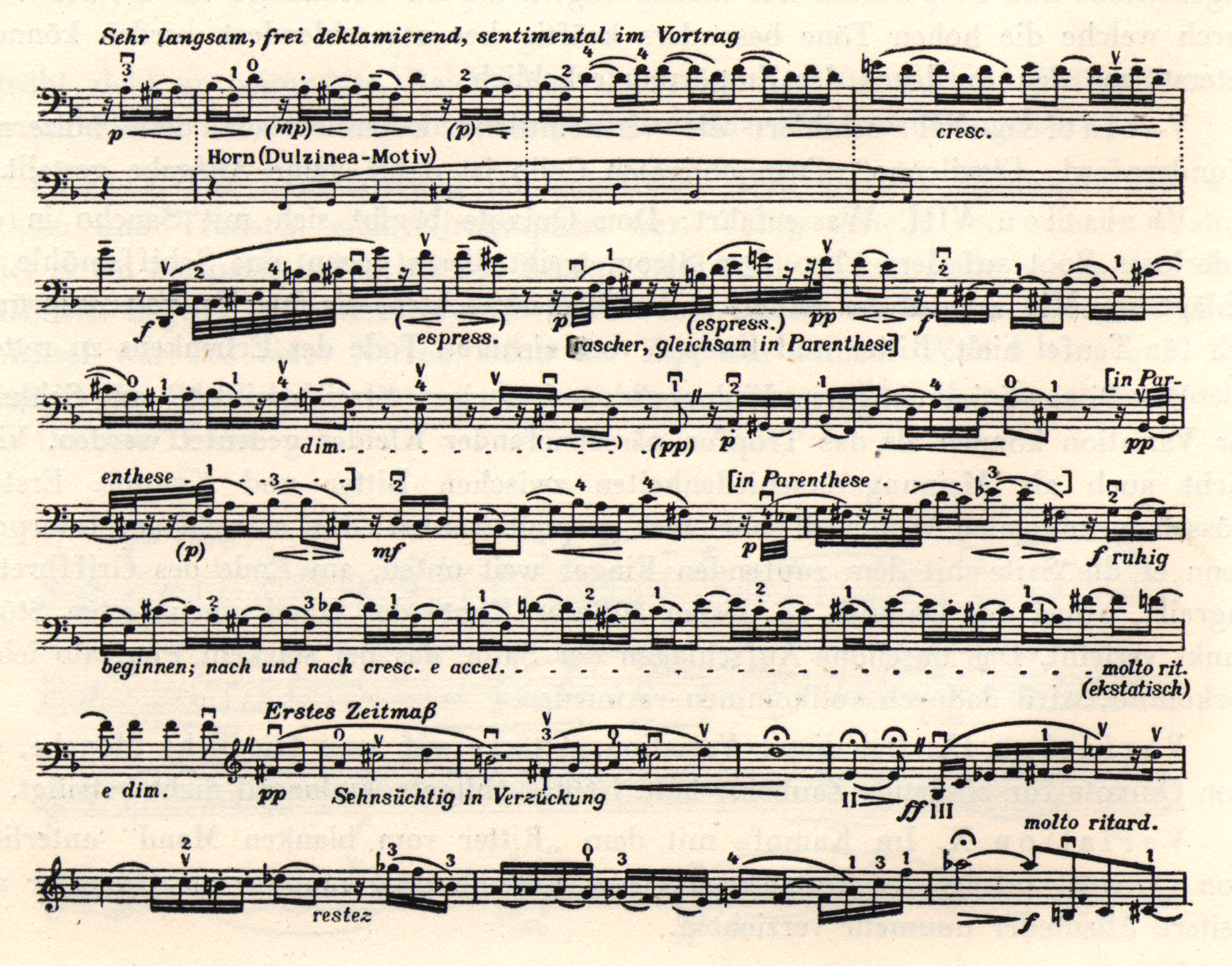

Finale. Disillusionment has set in. Don Quixote realizes that his poetic fantasies and aspirations were nothing but delusions. Completely cured of his madness, he leads a normal life among his own people. Soon he feels his end approaching. On his deathbed, he reviews his life once more. It has deceived him: “His fate was that of a fool, for time was contrary to his will. The tragedy of the idealist!” The Don Quixote theme is transformed into a calm, songful melody that requires a refined, sophisticated performance. The tone should be warm, but neither sensual nor sentimental. Noble, calm vibrato!

The section between rehearsal numbers 78 and 82 describes the anguish and turmoil of the man struggling with death.

At rehearsal 82, his strength gradually fades:

His resistance is broken. The dying man surrenders and breathes his last. Play on the C-string, with slow and diminishing vibrato and portamento.