Lecture-Analysis: Bach, Suite in G major

The faithful performance of Bach’s suites is among the most difficult tasks facing a cellist. This is especially true of the preludes, which, due to their often unvarying rhythm, can easily sound etude-like if the player is not able to read between the lines and discern the melodic line alongside the harmonic structure. Indeed, in some cases the player will even be able to discover and experience a distinct polyphony, as Ernst Kurth has demonstrated in his interesting book on Bach’s linear counterpoint.[1]

Of course, these things are not obvious at the surface. The interpreter must delve ever more deeply to uncover these treasures.

The purpose of this essay cannot be to provide an analysis from a compositional-technical point of view, but rather to establish productive principles for practice.

It’s worth noting, however, that cellists unfamiliar with the con discrezione style[2] will find interpreting Bach’s preludes particularly challenging. Unlike the later sonata form with its clearly defined themes, the main difficulty here lies in recognizing the scope and boundaries of Bach’s musical ideas. In his incomparably imaginative way, Bach dissolves these musical thoughts into motivically developed figurework, then builds them up through ever-changing rhythmic variations into a magnificent, monumental structure.

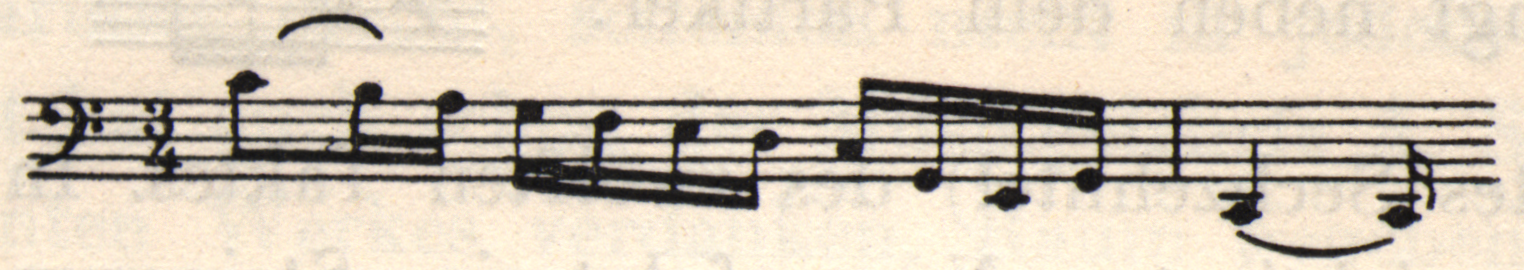

We find motivic movement like this at the beginning of certain pieces in the manner of a motto-theme. We can easily recognize this in the Prelude of Bach’s Suite No. 3 in C major, which opens and closes with this motto-theme:

This is different in the Prelude of the piece we are currently considering, the Suite in G Major. Here, we find movement that is more harmonic than melodic. Because of the unvarying rhythm, we are in danger of making it sound monotonous.

To prevent this, we must take special measures, outlined below.

The key of the piece is G major. This chord, and especially its fundamental note G, should be played somewhat broadly, in accordance with the piece’s calm, noble character, allowing the listener time for inner contemplation. (The similarity to the first Prelude in C major of Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier prompted the present author to use the indicated bowing.) If the first half of the first measure thus appears somewhat emotionally heightened, then the repetition (i.e. the second half of the second measure) should be played more simply.

Unvarying repetitions can be tiresome in both speech and music. A spirited person does not need to repeat themself. But if they are compelled to by circumstances, they resort to variation. We too must make use of such means. The expression, therefore, should as a rule be either heightened, or (cf. the echo effect often used by the old masters) weakened during the repetition of a motive. (There are naturally exceptions to this rule.) This creates light and shade. All the features that can help listeners understand the piece harmonically, melodically, and rhythmically should receive stronger “illumination.”

Repetitions, however, should generally be rendered in more muted tones. The harpsichordist employs the second manual (creating an echo effect) for this. Yet such passages should never be softened to the point of becoming lifeless. These subtle shadings are accomplished not merely in the realm of dynamics, but rather through rhythmic nuance (agogics), guided by emotional (or psychological) sensitivity; they resemble the “monochromatic painting” technique used in visual art.

The first four measures should therefore be performed in a way that makes their progressive harmonic sequence clearly recognizable. Pay particular attention to the F-sharp at the end of the fourth measure—it acts as a bridge to the E in the next measure. In the fifth measure, bring out the last four sixteenth notes more than the first five. A discreet sostenuto (see my chapter on sostenuto) will support the expression of this group of notes. The same goes for the seventh and ninth measures, but in such a way that the listener perceives a gradual intensification in the course of measures 5-10.

In addition to the following motivic fragment, measure 11 calls for emphases on G-sharp, G-sharp, B, G-sharp, and C (the first sixteenth note of measure 12).

In measure 14, the first nine sixteenth notes are the most important. Following this comes an increase in dynamics and expression over four measures, up until measure 19. From the sixth note of this measure, the expression gradually decreases again, only to begin a new intensification up to the inverted chord on measure 22. At its standstill on D, this measure represents the climax of the movement.

After this powerful and brilliant culmination, a long-held D slows the harmonic movement somewhat (measures 22-23), then becomes plaintive (measure 24), then increasingly more intense, until in measure 26. Here, at the beginning of the third beat of the measure, an initially quiet lament erupts into a loud outburst. (Observe the prescribed fingering, which should support making this expression possible.) Measure 29 and 30 can now sound confident and hopeful.

Before the sustained part begins on A in the next bar 31 with the melody initially below, this small motivic figure (shown in brackets) should be played expressively and restrainedly:

Although the D marks the end of this motive, it also marks the beginning of the aforementioned melody (a phenomenon we frequently encounter in Bach, as in music in general). This begins quietly but in a rhythmically determined manner, develops over bars 33 to 35 into a sonorous mezzo-forte, and then, just as gradually, fades away again until bar 37.

The following motive serves as an introduction to the now-ascending melodic line above the pedal point on D.

This should be played similarly to the passage mentioned above, that is, tenderly and hesitantly. From this develops the great crescendo that “crowns” the movement, until the tension finally resolves powerfully and brilliantly on the last chord.[3]

Determining tempo in the dance movements

Before we start discussing the performance of the next movements, we must address the question of how to decide on tempos for the individual dance movements.

The information that Quantz provides in his well-known music textbook, On Playing the Flute, which is otherwise so authoritative about performance practices of the eighteenth century, does not seem to be entirely accurate in every case. The musicologist A. Schering,[4] to whom we owe the new edition of Quantz’s work, has also allowed this view. According to Schering, Quantz’s teaching principles and rules[5] relate more to the so-called galant style, of which he was an adherent. (That is, “that style of writing which replaced the old contrapuntal polyphony and promoted pleasing melody as a precursor to the cantabile of Mozart’s time. It is impossible to pinpoint the exact year of this stylistic change,[6] but it is certain that Johann Sebastian Bach and his art were not influenced by it.”)

The tempos that Quantz specifies for various dance movements[7] are calculated according to the human pulse (which averages 80 beats per minute).[8] Regarding Quantz’s indications, Schering notes: “These tempos are generally extremely fast and, when applied to the dance music of the earlier period (that is, the Johann Sebastian Bach era), require some moderation.” Georg Schünemann[9] writes (in his History of Conducting): “These rough tempo markings are set quite high and appear to follow Quantz’s approach, which tends to be almost too fast. Quantz is thinking of dance movements within the framework of a staged dance performance, would would demand a very brisk tempo.” When it comes to Bach’s cello suites, we would find some of these tempos completely unworkable.

To give just one example: Quantz indicates the Sarabande tempo as one pulse beat for each quarter note, which would (according to Schering) be a metronome marking of 80! I believe that no good musician of our time would agree to choose the tempo of the Sarabande, which forms the lyrical resting point in the suite, so rapidly, and I therefore pose the question: Should there not have existed in Bach’s time—and perhaps even later—a distinction between the music one danced to and that which one performed for its own sake (regardless of whether they were also dance forms)? Quantz also bases this on page 207 of his book (new edition) in a manner that should enlighten today’s generation, where he says that dancers choose their tempos “partly due to the good meal they had eaten beforehand” or “out of the ambition that fires them up. Through this they can now easily lose security in their knees and, when they dance a Sarabande or Loure, where sometimes only a bent knee must carry the entire body, the tempo often seems too slow to them…”

According to my view, the tempo of individual dance movements in the various Bach suites cannot be established once and for all with complete precision. A comparison between the pieces in question among themselves will confirm this.

Just as the Preludes—which should really be understood as fantasias—must differ from one another in their movement because of their varying content, so too the six Allemandes, Courantes, etc. must never be played according to the same pattern. Consider, for example, the difference between the deeply melancholic and mournful Prelude of Suite No. 2 in D minor and the energetic, powerful, and brilliant Prelude of Suite No. 3 in C major. Playing them in the same tempo would be entirely unartistic—lacking individuality, and a sign of a lack of imagination and judgment. Thus, for example, the songful Allemande of Suite No. 2 demands a more tranquil tempo than that of the spirited, lively, almost joking one in Suite No. 3 or the energetic one in Suite No. 4. Even more striking is the different among the Gigues: the one in D minor shows an almost “Saxon” cheerfulness; that in E-flat major, a mysterious, fleeting liveliness; while that of the D major suite has something proud, almost weighty about it. We could go on with these comparative juxtapositions, but to do so is beyond the scope of this essay. We believe we have proven the need for tempo differentiation even through the few examples given.

Another question must be raised here. Can today’s generation still appreciate the kind of meticulous, detail-oriented performance style that eighteenth-century musicians practiced? The taste and sensitivity of the modern, high-strung person of the twentieth century are no longer the same as those in the Rococo era. So a painful adherence to every nuance that was customary in the powdered-wig era would amount to petty pedantry, which would certainly not be worthy of Bach’s great spirit. The warm-hearted, imaginative artist has the special ability to recreate the music anew each time, using the power of their personality to give it fresh, soulful life. Naturally, he must not let his creative impulses run unchecked in this revival, but must preserve cultivated taste and a secure stylistic feeling. A talented person knows how to make music in a stylistic, warm-blooded manner without pedantry.

Allemande

The opening melody of this movement consists of this “motto” and three and a half measures after that (up until the low G in measure 4).[10]

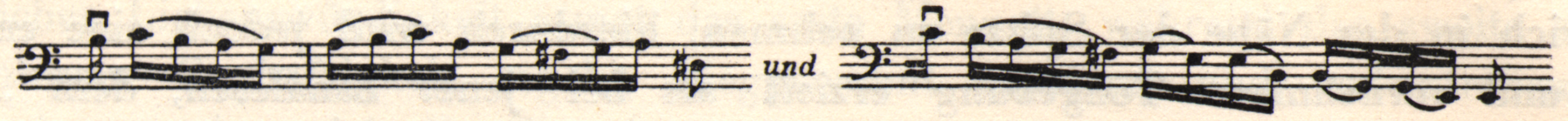

The bowing markings chosen by the editor to achieve certain tone colors must not cause a delay in the entrance of the note group that follows the last note of the motto. To avoid this danger, only use half the length of the bow on the separately bowed note. (The same applies to all analogous passages). In contrast to the energetic character of the “motto,” the melody (fourth measure) closes quietly, with an agogic emphasis on the first note of every pair of slurred notes. (Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach called these “Abzüge.”) Released from the last note of the theme, the melodic thread is now spun further. Like a question and answer, two groups of motives stand opposite each other:

Note that the individual sixteenth notes (on separate up-bow strokes following the three grouped under a down-bow slur) should be given exactly as much bow as the grouped notes receive, using plenty of upper-arm movement. The latter also applies to the individual notes in later measures over the course of the piece. The stereotypical habit of so many players to bring out a pronounced ritenuto, not only at the end of pieces but also at the end of sections, is reprehensible. Not every section or phrase demands a broad conclusion. But if the character of the piece demands it, as for example in this Allemande, the tempo must already be slowed on the cadence and restored at the entry of the tonic triad. In this case, slow down starting from the fourth beat of measure 15 until the first note D of measure 16. Then let the following notes simply lead to the end of the section without any drama or tempo changes.

In the second part, these same principles apply. The small appoggiatura D in measure 19[11] causes many players to make clumsy mistakes. The short motive is light and rhythmically even, as follows:

An inexperienced player with poor bow technique will have the misfortune of emphasizing C instead of the appoggiatura D on each strong beat. It’s one of those cases where the bow arm does the thinking instead of the head! The same applies to the F-sharp in m. 20. The trill on G-sharp in measure 21 would perhaps be better replaced by a mordent. The trill marking may not belong here at all—it should probably be on the B in measure 23 instead. While this note has no trill in the original manuscript, it would make musical sense given how often Bach uses trills in similar contexts. Measures 26 and 27 should be performed with great ease and grace, whereby the added trills support the given character. If the repeats are taken, the ritenutos mentioned above should be applied less intensively the first time than the second. The biggest ritenuto naturally takes place at the end of the piece.

Courante

The character of this piece exudes splendor and dignity. The tempo is moderate. In the mid-seventeenth century, composers distinguished between ordinary and fast Courantes, which correspond to the later Gigue or Canarie (according to Riemann). None of the Courantes from Bach’s Six Cello Suites fall into the fast category. The present one requires a fairly weighty, majestic tempo. The given bowing in measure 5 (with upbeat) may initially puzzle some players, since it requires them to use longer sections of bow in a heavy, accented manner on up-bow strokes near the tip of the bow. However, this produces a more energetic and distinguished tone than the banal solution (the usual down-bow at the frog or in the middle of the bow) favored by “orchestra section cellists.” If this specific bowing is done properly, with the aforementioned notes taken broadly in the upper half of the bow, there’s no doubt which solution is preferable from a musical-aesthetic standpoint.

We should not let awkwardness or convenience determine our artistic choices. Measure 28 and 30, which are easy and graceful to play, bring a little variety to the performance. After this brief episode of tenderness, the expression of energy gradually revives, increasing steadily until the powerful conclusion.

Sarabande

The thirty-second notes in measure 3 are crucial for determining the tempo of this movement. It would be tantamount to desecration if the interpreter of this magnificent piece of music did not strive to capture the sublime mood contained within it by correctly executing even the smallest of fractional note values. These thirty-second notes therefore should not be played in a rushed manner, but beautifully sung. This requirement suggests that we should choose a very calm tempo. From the third quarter beat of the fifth measure onward, the soulful expression demands a small agogic emphasis up until measure 7, whereupon the execution should broaden until the conclusion of the phrase.

While the first section (measures 1-4) should be played as smoothly as possible despite the frequent bow changes, the carefully notated articulation marks can help shape the melodic line more vividly in other sections. This advice also applies to the second part of the Sarabande. The small “two-voiced” passage in measure 15 requires special attention. So that the sixteenth notes of the lower voice do not overpower the sustained D of the upper voice, it is recommended to let them enter in a somewhat delayed way, stretching the upper voice slightly, so that the sustained D resonates longer than the B in the lower voice. To keep to the overall beat, the sixteenth notes in the lower voice should then naturally accelerate a little. (Organists use the same procedure to create accent effects.)

Menuet I and II

It is well known that pre-Haydn menuets move at a more measured tempo than those of later epochs. When determining the expressive character of the present work, it is important to remember from the outset that the first menuet is followed by a second!

Both menuets have fundamentally different moods. The first menuet is bold and assertive, the second gentle and delicate. The contrast between major and minor keys is not the only difference between them. Self-confident decisiveness combined with chivalrous gallantry characterize the first menuet, whereas the second reveals itself in shy timidity. Accustomed to being victorious and resistant in battle, the characters of both menuets thus stand opposite each other, yet they have one thing in common: gracefulness. The cellist’s imagination should focus on bringing this mood to life through appropriate bowing technique, evoking the splendid court festivities of Louis XIV’s era, where the elegant courtly minuet created enchanting, timeless images for posterity. Without this historical awareness, it would be difficult to achieve the deeply expressive performance that represents the highest level of refined musical sensitivity. Such artistry requires the kind of intuitive understanding that comes as a gift of inspiration!

The first menuet begins in a proud, bold mood. In the second part, the expression changes between measures 13 and 16 to a more graceful, conciliatory tone. Measures 16 to 20 feature a question-answer gesture, after which the energetic mood gradually reasserts itself, so that the piece concludes in a decidedly vigorous manner.

The second menuet begins hesitantly and shyly. Measure 1, 3, 5, and 7 should be played with rubato, so that the first three eighth notes are always somewhat held back, and the three eighth notes that come after them are correspondingly accelerated to restore the rhythmic balance of each measure.

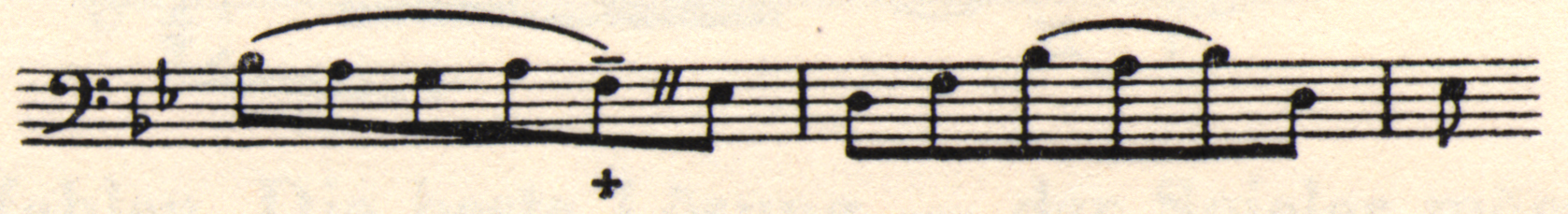

In the second part of the second menuet, the fourth measure (measure 12) demands special attention. In metrical terms, for the sake of symmetry, it should correspond exactly to the rhythmic division of the second measure (i.e. measure 10):

But it actually reads:

Therefore, the sensitive interpreter should create the impression of symmetry by lengthening the note F, then pausing appropriately before E-flat, a passing tone which serves as an upbeat to the following note group:

Playing through it in an undifferentiated way would be very spiritless. Perhaps it should be remembered that on the da capo of the first menuet, the chivalrous-decisive character should immediately resume.

Gigue

The tempo of the gigue is fast. In a later epoch, this piece might have been described as “con spirito,” for it contains a great deal of wit and humor. Anyone who can read between the lines will easily recognize this. The theme begins bubbling forth in a cheerful manner that after two measures receives a decisive, almost roughly emphatic response. The chord in the fourth measure should not be arpeggiated in order to maintain an energetic expression. Measures 5 to 8 return to the character of the opening, while the next measures, 9 to 11, should be played with jokingly exaggerated sentimentality.

The sudden musical entrances in the second part (measures 14, 16, 21 to 24) sound like abrupt, defiant outbursts:

Measures 25 to 27 again demand the same expression as measures 9 to 11. Measures 28 to 31 require lightness, grace and humor.

By taking a small breath after slightly shortening the first eighth note, and by delaying the entrance of the short motif mentioned earlier (which returns here), this passage takes on a gracefully cheerful character. This cheerful mood should remain dominant through the end of the piece, even during the urgent, almost overwhelming sequences in measures 31 (second half) and 32, and the energetic closing measures.[12]

- Becker's note: "Grundlagen des linearen Kontrapunkts [Foundations of Linear Counterpoint]. Bern: Drechsel, 1917." [The Austrian-Swiss music theorist Ernst Kurth (1886-1946) wrote several influential books, including one on the then-new field of music psychology.] ↵

- Becker's note: "Max Seiffert writes about this: 'Playing con discrezione is a characteristic technique of the Frenchman L. Couperin and the German J. J. Froberger, which they adopted for their keyboard playing from the French lute art of Denis Gaultier. It consists of not playing certain linear sequences of figures as strict melodic lines, but rather recognizing them as successive sounds that are components of a harmonic whole, and accordingly blending them from a sequential pattern into a more simultaneous, surface-level unity, thus bringing them into a unified harmonic context." This "discerning" style encompasses German keyboard art up to Bach and Handel. From keyboard music, this style also spread into violin repertoire, where it replaced the earlier technique of playing full chords using altered tunings." [Becker quotes the German musicologist Maximilian Seiffert (1868-1948), an early music expert and editor of the Händel-Gesellschaft. The performance direction con discrezione ("with discretion" or "with discernment") implies freedom of interpretation of early music, within the bounds of good judgment.] ↵

- Becker's note: "It may perhaps seem strange to some players to see the two consecutive ascending melodies marked with different bow directions—the first with an up-bow, the second with a down-bow. The main reason for this is to create contrast between the two passages so that an intensification is achieved. While the first melody somewhat ornaments the sustained note on A, the second builds powerfully and penetratingly on the pedal point D, with the down-bow direction significantly supporting the effect." [Becker refers to his own edition of Bach's Suites.] ↵

- The German musicologist Arnold Schering (1877-1941), editor of the most widely-used German edition of Johann Joachim Quantz's Versuch einer Anweisung die Flöte traversiere zu spielen. ↵

- Becker's note: "Insofar as they are not of a general nature and therefore still apply today." ↵

- Becker's note: "According to Schering, the transition was underway in the fourth decade of the eighteenth century." ↵

- Becker's note: "Schering's new edition, p. 209." ↵

- Becker's note: "Ibid., p. 210." ↵

- Georg Schünemann (1884-1945), a German musicologist. ↵

- Becker's note: "The stroke style prescribed here corresponds to that of the manuscript considered to be the original in the Berlin State Library." [Becker refers to the manuscript in the hand of Anna Magdalena Bach.] ↵

- Becker's note: "Cf. Quantz, On Playing the Flute, chapter 8. See also my essay on appoggiaturas, as well as Beyschlag's The Ornamentation of Music. ↵

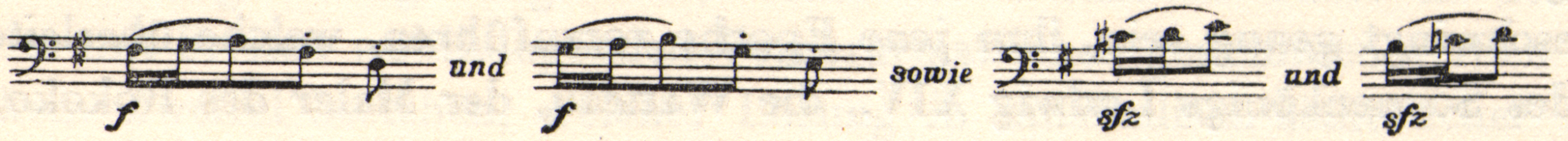

- Becker's note: "Connoisseurs of strict observance would perhaps prefer the following bowing pattern as more appropriate to the style of the Gigue:

However, the editor believes that this small stylistic liberty does not commit any violation of style. The performance is made more interesting precisely through the variation of the character within the same piece. Furthermore, it will interest the reader to learn that the first measures of this piece are indicated like this:

in the manuscript that is considered to be the original (Berlin State Library)." ↵

in the manuscript that is considered to be the original (Berlin State Library)." ↵