Lecture-Analysis: Dvořák, Concerto in B minor, Op. 104

Allegro[1]

The orchestral introduction that precedes the entrance of the solo cello provides a clear overview of the character and thematic material of the first movement. The soloist must therefore listen carefully to the introduction and plan their interpretation of the work accordingly.

It is precisely in this respect that a more symphonic work like this one is very different from a concerto in which the orchestra only performs the function of an accompaniment.

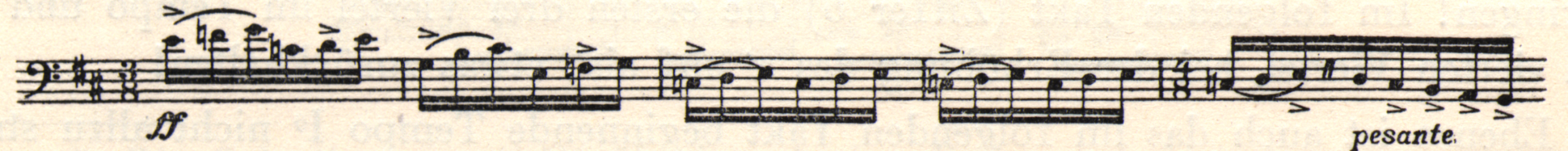

Therefore, we cannot avoid lingering somewhat on the introduction. The movement begins somberly, but with rhythmic decisiveness. With each renewed entrance of the main theme’s opening motive, this decisive character builds up to something heroic (rehearsal 1).

From the eighth measure before rehearsal 2 and onward, the heroic character gradually lessens again. After a multi-measure diminuendo, a short episode introduces a transitional theme in the bass, which is repeated by the woodwinds. At rehearsal two, there is a short introduction (which utilizes the main motive) to the second theme.

The latter, with its warmth and intimacy, contrasts wonderfully with the main theme; it should be performed with great simplicity. As it progresses, its warmth and power steadily increase until rehearsal 3, where a new chivalrous and energetic episode begins. Initially in the style of a defiant uprising, it soon subsides into conciliation, allowing the close of the introduction to fade away quietly.

The B major triad, held at pianissimo for a full measure before the solo entrance, creates great anticipation in the listener, thereby preparing most effectively for the cello solo. Despite the marking “quasi improvisando,” it must sound strong and determined!

Only with regard to rhythm is a certain freedom allowed; the sixteenth notes may be taken somewhat more broadly and the half-note Bs may be shortened accordingly both times, so that there are small pauses after the first and second measures.

It is quite inadmissible to crescendo on the half-note Bs, as one often hears.[2] Rather, we should do the opposite: accumulate all energy at the tip of the bow and diminuendo towards the frog!

Shouldn’t the second measure of the theme be played on the D-string in the interests of greater homogeneity? —No, we cannot do without the shining brilliance of the A-string here; the cellist must have learned to handle the open A-string so that the tone does not stand out.

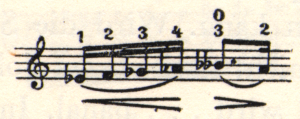

The third measure of the theme:

should be rhythmically energetic, with the final D-sharp somewhat shortened so that the following chord on the last beat of the measure can act as an upbeat to the next measure. (The chords are best played by striking all the strings simultaneously and holding the note to the full value, especially on the third beat of the measure.) The last of the chords in the fourth measure, which comes in on the fourth beat, is played on on up-bow. It should be arpeggiated and sustained only briefly, so that the third and fourth beats of this measure ebb and flow into each other.

When the theme repeats in the fifth measure, it would be faulty to sharply separate the eighth-note chord on the downbeat from the theme, since it actually represents an arpeggio:

The performance of the next three measures is analogous to the preceding ones.

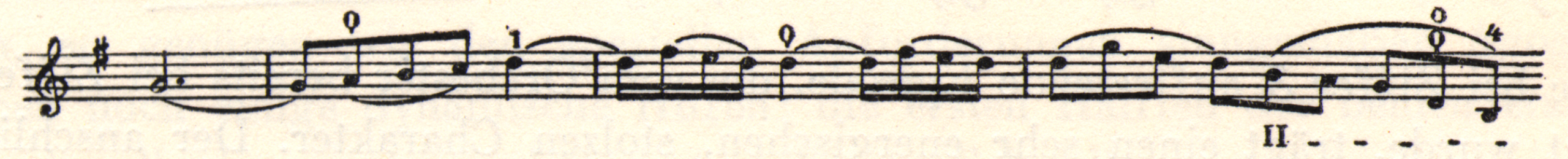

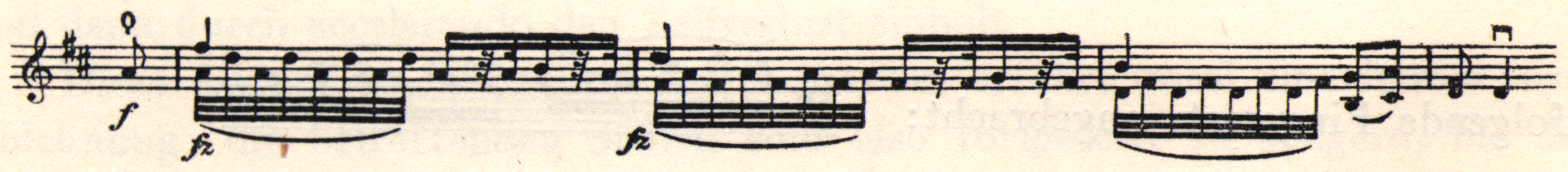

The ninth and tenth measures should be played very rhythmically, with scrupulous observance of the prescribed accentuation! There should be no involuntary emphasis on the up-bow notes F and D, and no slackening of the rhythm here:

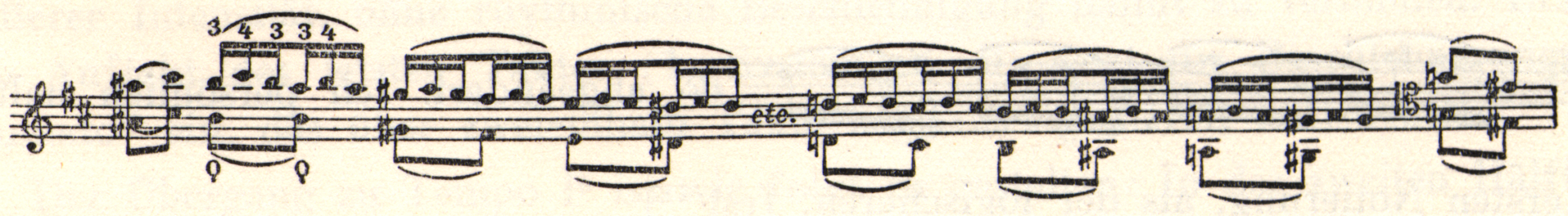

The cadenza-like measures (11 and 12 of the opening solo) can now be played very freely and interestingly, yet quite naturally. —One should play them as if they are in 3/8 time, as follows:

The thirteenth measure should be strictly rhythmical and the next one rubato, but while staying in time and not changing the total time value of the measures. The same is the case in measures 14, 15, and 16.

Next comes a series of trills alongside sequential patterns in the orchestra. These should press forward, reaching a climax two measures before rehearsal 4.

The following section sees a return to the original tempo, which, however, should be somewhat more lively than at the beginning of the movement (as the composer clearly indicates with the designation “vivo”). Here, a rhythmically altered version of the theme calls not for a delicate spiccato, but for an energetic, “hammered” martellato-spiccato (best performed slightly below the middle of the bow). Note the fp marking on the Bs: this is usually done too weakly on the up-bow, compared with the down-bow!

Four measures before Rehearsal 5, beware of rushing! The soloist should not be driven along by the accompaniment; acceleration of the tempo would be wrong here because the passage leads to a particularly heroic instance of the main theme! Here, it is good to sustain the half notes, because the accompaniment moves rhythmically and the solo part is not meant to be played freely. It is best to avoid the “ad libitum doubling” in octaves that some players add to this section, since experience shows us that the force of the bow is acoustically strongest when we play solely on the A-string.

While the phrase that first appears in measures 5-7 after rehearsal 5 should still sound energetic and excited, it should move with more tenderness and calm in the repetition in the lower octave (measures 9-10). The ritardando that leads to the calmer tempo of the second theme (via bars 10 and 12 after rehearsal 5) must not be extended too far at the end. These last four measures mediate the tempo between the two themes! Therefore, the deceleration must develop logically, without any rhythmic peculiarities, until the desired tempo. (The tempo should be M. M. quarter note = 100!) This makes it possible to create the impression of improvising over the upbeat to the second theme, without inhibiting the natural flow of the melody!

Tender, restrained, otherworldly,[3] this songful theme begins in piano. (Not pianissimo—this marking is only for the accompaniment!)

In the first quarter beat of the eighth measure of this theme, the expression builds in intensity without adding rhythmic acceleration. Only with the upbeat of the last measure (first system, page 9) does the acceleration to the “animato” begin, glowing brilliantly over two and a half measures.

The transition to tempo primo should be structured as follows: in the second half of the measure before rehearsal 6, where the harmony has a dominant seventh chord, add a “calmando”! In the following measure (i.e. the first measure of rehearsal 6), keep the tempo for the first three beats, then slow down slightly on the fourth beat when the A goes up to an A-sharp.

Likewise, the tempo primo that begins in the next measure does not need to be too strict. A marked tempo change from ritenuto to tempo primo can sound stiff and awkward. If one allows oneself to begin calmly at the Tempo primo, however, and to accelerate gradually over the course of the first four measures

However, if we allow ourselves to begin the section marked tempo primo quietly and gradually speed it up a little over the course of the first four measures, meaning that we only get to the tempo at the next two, the passage sounds clearer. —A gradual “poco a poco calmando” then brings the music back to a quieter state, leading into a new episode (which appears in the second measure of the first system on page 10), and this new section should be played calmly and in a singing style. The chords in measures 1 and 2 (third system) can be arpeggiated to emphasize the singing melodic notes in the upper voice.

In the second measure of the fourth system, let the sixteenth-note figure start calmly in mezzo-forte, then gradually increase to fortissimo. The climax comes on the third beat of the next measure.

The situation is similar in the second measure of the second system (p. 11). The broken chords in measures 2 to 4 of the third system should be played rubato, beginning broadly, then accelerating up to the main thematic motive (which again must be strictly rhythmical). If the entire passage is not phrased in the manner indicated, it will sound somewhat dry and unimaginative.

In the magnificent orchestral setting of the beginning of the development, the first theme is transformed in a variety of guises and shades. At rehearsal 10, the soloist intones a mournful, deeply felt melody (a broadening of the first theme), which the oboe takes over and continues

In a magnificent orchestral setting, with which the powerful development begins, the first theme is transformed in various forms and shades, with the solo instrument (number 10) intoning a sad, deeply felt melody (broadening of the first theme). 16 measures in, the oboe takes over this theme while the solo voice steps back into the accompanying role. In the two measures before the first system of p. 14, the soloist would do well to prepare for the animato that starts there. In no way should they drag or be played with too much expression! The voice-leading here has only harmonic significance; the animato should not be exaggerated.

The last measure in the second system should be played with a slight forward momentum through the first half, building up to the D-sharp on the third beat, which should be held expressively. From there, through careful timing of the remaining notes, return to the proper tempo. Despite this rubato, the overall duration of the measure must remain unchanged. Freedom, but no anarchy! ——

In the first edition of this concerto, the figure that begins in the first measure of p. 14 (with the exception of the last measure) extended in the same pattern up until rehearsal 12. Later, it was changed—probably for the sake of easier playability—unfortunately!—to this:[4]

I personally stick to the first notation as the more logical one.[5]

The first octave G in the fifth measure after rehearsal 12 should have a particularly strong sforzando accent.

For the sake of absolute security in the ensemble playing, one may take the liberty of playing the chromatic octave scales the following way on the second and third beats of this measure, so that the orchestral entrance on the fourth beat is together with the solo cellist’s A-sharp:

The second theme, which now appears in noble and radiant fashion in B major, begins in the orchestra and continues in the solo cello part. Here, the soloist has difficulties creating the impression of imposing power (p. 16, first system, first two measures). In the next measure, the diminuendo should not arrive at pianissimo too early: this should preferably appear only at the conclusion of the dotted half notes.

Everything applying to the first part of this movement applies also to the recapitulation. —Only the Coda remains to be discussed (rehearsal 15).

Here, the main theme reappears triumphantly, first in the orchestra for four measures, then in the solo cello part. The composer’s instructions (“grandioso,” “molto appassionato,” and so on) speak for themselves!

Even if we have permission (marked “ad libitum”) to play the theme in octaves, it is better not to make use of this here! We can project much more incisively with just one voice played on the A-string. For the octave figure that occurs in the last measure of p. 18 and the first measure of p. 19, there is a third solution. The present author has always used it publicly, assuming that it best meets the composer’s intentions:

The fact that the triplet notes must be omitted on the fourth beat of the figure in the measure before “più mosso” due to the limits of extending the hand is irrelevant. For an effective representation of the ascending double-stopped sixteenth notes (p. 19, last system), add an accent to the first of the sixteenth notes in each beat. For the sixths on page 20, this is the best fingering:

We must strictly avoid audible position shifts here! (During shifts, reduce bow pressure.) There must be strong accentuation!

To prevent the “molto ritardando” in the third bar of the second system from becoming limitless, the soloist should be careful to play the second beat without ritardando, so that the slowing-down only begins on the second half of the second beat when the orchestra enters!

Adagio ma non troppo

The movement, composed in the so-called “large song form,” brings a simple but solemn theme at the beginning. Right from the start there are two places where a careless interpretation can easily damage the nobility and beauty of the melodic line. If the sixteenth note c’ at the beginning of the theme is not held to its full value (as often happens), the melody loses its solemnity and becomes…banal. In the following measure it is important to avoid an involuntary portamento from D to G (through extreme stretching of the hand, or through a rapid, inaudible jump), and instead to use one to descend from G to D. The dynamic markings in measures 12 and 13 in the solo part are incomprehensible to some players. They should be understood as follows: two before rehearsal 1, the dynamics swell powerfully in strength and expression, reaching their climax at the beginning of the following measure. While the orchestra now decreases in dynamic, the soloist should begin a further crescendo toward the G of the next measure! But our resources are insufficient for that.

The player therefore has no choice but to use a kind of fp accent on the half note B, as inconspicuously as possible, and then to crescendo again, allowing the theme to fade out in a large and broad manner (while extensive developing the A on the third beat). There should be a portamento between B and A, using finger alternation![6]

In the third and fifth measures after rehearsal 1, for the sake of beautiful ensemble playing, the first three sixteenth notes must be played very strictly in time; on the other hand, the note values falling on the third quarter require an extensive rubato. The sixth and seventh measures of rehearsal 1 should press forward a little. In the eighth measure the tempo is completely restored, remaining unchanged until the third beat of the third measure (last system of p. 21). Here, we should view the eighth-note triplets as the upbeat to a new phrase; we should therefore play them somewhat more markedly and broadly than the preceding triplets.

In the following measure a lively mood now begins in conjunction with a quickening of tempo. In the third measure of the first system of p. 22, this transitions into a poco accelerando. However, it cannot include the bar preceding the tempo primo, because otherwise the tempo primo would enter suddenly, which cannot have been the composer’s intention. Rather, the intended measure should convey the transition to the tempo primo through a corresponding calmando! (In the subsequent motive leading to the theme of the middle section, the orchestra usually plays the sixteenth note too short in the second measure!)

The melody of the middle movement that now begins requires a broad, sweeping bow stroke using all the bow hair!

Rehearsal 3: a A dialogue rises plaintively between orchestra and solo voice; at the second entrance this should sound somewhat more liberated, more urgent!

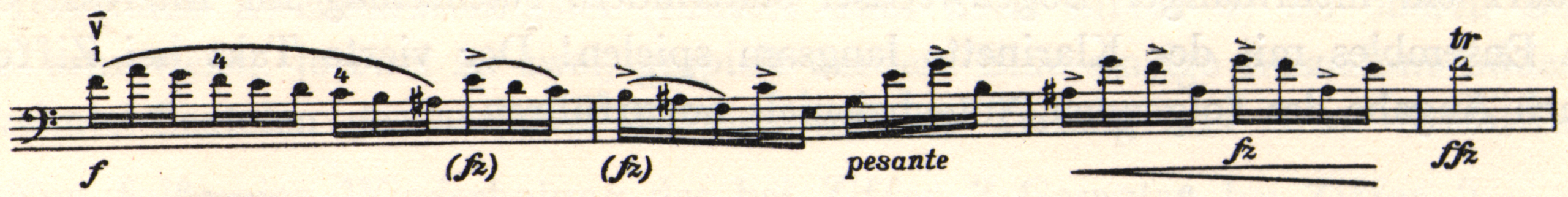

At the “poco animato” the cello takes up the passionate melodic movement of the orchestra and then takes it further. The fingering for the four sixteenth notes on the second and third beats should be as follows:

In order to best serve the composer’s intention, the thirty-second notes that follow (fifth measure after rehearsal 4) must be played very softly in the upper third of the bow, two by two. The only exception to this is in the sixteenth-note sextuplet in the sixth measure of rehearsal 4, where it should be divided three by three.

Now, at rehearsal 5, follow the same instructions as for rehearsal 3.

Cadenza: at the conclusion of the solemnly-played “Meno” in the orchestra, the solo cellist must come in as unobtrusively as possible, almost “sneaking in,” since it initially does not have the most prominent part. The conclusion of the figure should be on the D-string. There should be a “breath” after the long fermata on D; then the line emerges—melancholy, dreamy, in great repose!

Since everything at this point depends on correct bow usage, here are some brief hints: make sure there is a good connection between the D with the sixth (G-E) in the part in the first measure with the pizzicato accompaniment! The cadenza begins on an up-bow, so that the theme also has an up-bow. In the next measure, use the same bowstroke as in the preceding on, and take a “breath” after the first beat! Play the double stops F-sharp -D and E-C in the last measure of the first system (page 27) with a broad stroke! In the fourth measure of the second system the quarter notes must be well sustained; imagine them subdivided into sixteenths.

For the sake of good ensemble playing between the solo cello and flute, it is advisable for both instrumentalists to imagine the sixteenth-note movement here as well, so that each connection proceeds as smoothly as possible.

In the sixths that come after this, the bow must leave the D-string in time for the left-hand to play the pizzicato accompaniment: it must not interrupt the bow’s movement on the A-string in the slightest! Begin the thirty-second note arpeggios softly, with a slight crescendo into the next measure, then execute the following “Poco stringendo” in a very logical manner! During this “Poco stringendo,” the soloist must not start arbitrarily rushing, but must take into account the degree of acceleration that is going on in the orchestra. The forward movement is mutual; it requires both parties to agree so that the passage does not make a pitiful impression, rhythmically speaking!

The same applies to the ritenuto that follows, which begins a few measures before rehearsal 7 and brings back the old tempo. At rehearsal 7 the charming episode from rehearsal 1 is repeated, but here it should sound particularly tender and gentle. This motive:

which alternates between the solo cello and the orchestra at the six-four chord to the pedal point on D, should sound with evenness and composed calm. The penultimate measure of this system can be understood as an augmentation of the aforementioned motif. There should be a caesura before the final third (A-C), so that through good connection of the first two quarters with the first eighth, this third recognizably becomes the upbeat to the following group of notes.[7] Whatever bow strokes the soloist may use, he must always be mindful of logical phrasing. Multiple bow changes may take place on the trill measure. In the interests of good ensemble with the clarinet, play the Nachschlag slowly! The fourth measure of rehearsal 8 should be played according to the following example:

The same procedure is repeated in the lower octave. In the last measure of the third system, the first sixteenth-note G should be somewhat held, since it represents the conclusion of the preceding phrase rather than the beginning of a new one. The sixteenth notes that follow form the basis on which the next figure is built. The trills in the third and fourth measures of the penultimate system should be played without a Nachschlag; it is a good idea to hold the F-sharp slightly instead as a connection to the step up to G that occurs after it. The piece now fades away in a magical, dreamy mood!

Allegro moderato

The introduction to this movement begins in mysterious, dark colors. Soon, the music rises to a heroic height. The solo instrument now takes over the theme in a proud and resolute manner! At this theme’s conclusion, the sixteenth-note quintuplet should be played with a ricochet stroke; there should be an accent on the following D (and three up-bows in succession). Do not make an involuntary accent on the C-sharp!

For the entrance beginning in the third measure of the second system (p. 31), note that this motive must always be sharply accented.

At this point, it is essential for the bow mechanics to produce accents through “abrupt” hand and finger movements; the bow pressure must also remain constant during the rest! The passage should be played once just above the middle of the bow, the other time in the lower quarter of the bow! Avoid getting too close to the tip!

The subsequent eight measures should be played generously, passionately, and somewhat freely, but without ever destroying the rhythmic structure. Observe the strictest rhythm from the fourth-to-last measure of the last system of p. 31!

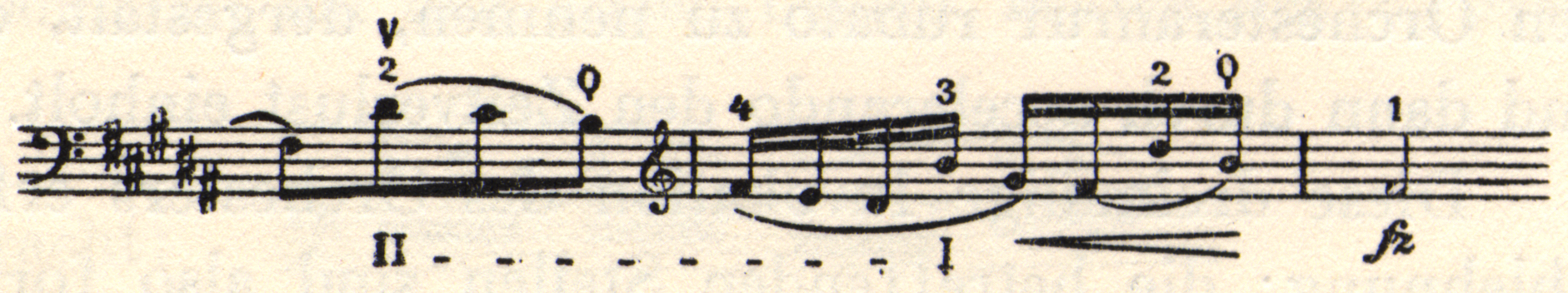

The first three measures of p. 32 are not entirely easy to get completely clear, so this hint for bowing and fingering may not be superfluous:

The episode appearing at rehearsal 3, which already appeared in the orchestra part at rehearsal 2, has a very energetic, proud character. The subsequent, more singing section (fourth system of p. 33) gains in folk-like characterization[8] if the player remains in position for the E-sharp in the first bar, but plays the next bars up to the start of the repeat on the A-string (avoiding involuntary portamenti!).

At rehearsal 4, play the “poco meno mosso” with a yearning expression! Since this figure returns a lot, vary it through changing the fingering and making small dynamic shadings within the prescribed markings! This advice also applies to all the following measures up until the tempo primo. —Toward the end of this section after rehearsal 5, the expression increases in strength and movement. At the tempo primo (last two measures of p. 35), it is advisable to use two bowstrokes to a measure so that the sixteenth-note triplets will be powerful and clear (with a strong emphasis on each of the first notes of all triplet groups).

The present passage can present problems for bowing due to the necessity of having to get over the strings very quickly. The student who has learned to apply the theories in the first part of this book in practice will easily recognize the advantages this offers when solving these passages. For normal-sized hands, the following fingering is appropriate for the first two measures of the second system:

At p. 37, the fortissimo demands special handling of the bow for each triplet. In order to increase the brilliance of the scalar run, and to ensure the security of the re-entrance of the orchestra, here is a suggestion that has proven effective in concert performance: begin the scale in a calm tempo, then speed it up so that its last note, C-sharp, coincides with the orchestral entry on the upbeat A.

As for the bowstroke, slur the first two notes and separate the rest. Accent on the first G!

The eighth-note triplet figures leading back to the main theme (p. 38, penultimate system) are among the most difficult parts to perform of the entire concerto. —The player who understands this passage well know without further explanation that the sparse performance indications in the score are not sufficient! —Here the art of the performer must intervene to come to the composer’s aid.

On the first half of both the first two measures, we stretch out the triplets and play them expressively. In the second halves of both the measures, we should accelerate them. The third measure should be evenly in time and the fourth almost evenly. On the fifth measure, we should strongly emphasize the B-flat. On the sixth, we should play very calmly, with an emphasis on B-natural. If we do this, we satisfy the need for meaningful agogics. In addition, we can help with some dynamics: the first halves of both of the first measures can be expressive, the second halves less so! We can make a slight “swell” from the fourth measure to the beginning of the fifth! We can decrease the dynamic into the sixth measure, before swelling again, increasing in expression as we get towards B-flat. On the long note (E-sharp) of the next measure, make a significant diminuendo, then play a portamento into the F-sharp (dolcissimo)! The tempo accelerates to the fourth bar and culminates in the “molto ritenuto.” This time, the main theme appears with great simplicity.

At rehearsal 9 (Moderato), the first quarter note should be played on an up-bow. There should be a separation between it and the next note. Do this similarly in the ninth measure of rehearsal 9. We should observe the markings “dolce” and “moderato,” thus avoiding a robust or march-like tempo.

In the section between rehearsal 10 and 11, the following instructions have proven more practical than the printed bowing: play the first ten measures with one bow to a measure; in measures 11 and 12, play four sixteenths in one bow; in measures 13 and 14 play as before (i.e. with eight sixteenth notes on one bow), and then again

In the section, the following notation has proven to be more practical than the prescribed bowing: the first ten measures in whole bars on one bow, the eleventh and twelfth measures each with four sixteenth notes on one bow, the thirteenth and fourteenth measures as in the beginning (eight sixteenth notes on one bow each), then again go back to playing four sixteenth notes on one bow.

Here are a few hints regarding fingering: the seventh and eighth measures should be played in position, the last two measures like measures 11 and 12.

At the “Meno mosso” (rehearsal 11), the ascending figures should be played rubato as an answer to the orchestral “call,” beginning somewhat more slowly, then catching up with an accelerando.

This threefold “invocation” by the orchestra is answered ever more sharply; the relevant passages should be progressively intensified until the “redemption” of B major appears.

Despite the fortissimo the composer has written in the solo part, the soloist must be considerate of the solo violin, since here it has priority and should not be drowned out. This is the case up until rehearsal 12.

Further development takes place in a mood of stormy agitation, reaching a climax (like that of the entire piece) in the powerful, solemn chords of the horns, trumpets, and trombones. (This is a B-major version of the main theme of this movement.)

Noteworthy in in the last section: in the twelfth measure after rehearsal 12, play the first sixteenth note fortepiano, then immediately crescendo to fortissimo. In measure 15, accent the F-sharp.

The thirty-second note figure before rehearsal 13 should be slurred into the C on the downbeat. A short break, as indicated by the dot on the preceding G, should not be missed!

In the fifth measure of this section for the woodwinds (penultimate system of page 45), there needs to be a “subito diminuendo,” otherwise the thematic entrance of the soloist will not be audible!

The soloist now has to deploy all their available power to project the sound. The best solution for bowing and finger, based on experience, is shown here:

From the “meno mosso,” the entire section up to the end of the piece requires a fine sense of sound, because we need to think through whether a passage is of thematic importance or if it only has harmonic value.

The long low F-sharp, beginning five measures after rehearsal 14, is usually too strong against the B bass note in the double bass section, making the listener think it is a 6/4 chord instead of the tonic triad of B major!

In the three measures that follow, each of which should be taken on one bow, we should use ample amounts of bow.

In the eleventh measure after rehearsal 14, play F-sharp, E, and D-sharp on the G-string! For measures 17 and 18 of rehearsal 14, see this example:

Regarding the two measure that lead into the high trill on B, try this:

While the solo instrument now indulges in brilliant, powerful trills, the main theme of the first movement resounds in its original form once more in the orchestra, whereupon the cello transitions into a deeply felt, melancholy melody that gradually fades away, but swells once more in excitement on the long final note. It is like a final flaring-up before the end.

The orchestra concludes the movement, which began so gloomily, with short, lively rhythms.

Postscript

The above suggestions and modifications may perhaps seem strange to some players because they do not reflect common practices, especially in the coda. However, these indications were not made with regard to the most convenient solutions, but rather from aesthetic considerations: in the sense of thoughtful phrasing, of tone colors that adapt as much as possible to the respective orchestral colors.

Objections that could possibly be raised against these artistic liberties can easily be refuted[9] by the following historical reminiscence. In the year 1897, on April 30, the author played this work at the request of the composer in a concert at Prague Conservatory, at which occasion the conception of the work manifested in these instructions received the sanction of the Bohemian master himself. In fact, Dvořák himself said that these small changes—which make it easier to play with the orchestra and improve the concerto’s overall effect—were completely in keeping with his intentions!

- Becker's note: "Since not every cellist owns a full score of this work, this analysis is based on the piano score." [Becker is using the Simrock edition of 1896.] ↵

- Becker's note: "See the section on meaningful musical emphasis." ↵

- Becker uses the German word weltvergessen ("world-forgetting"). This could also be translated as "dreamlike" or "lost in thought." ↵

- Most present-day players play this section with the ossia proposed by Pablo Casals in his recording of this piece. This version appears in the widely-used edition by Leonard Rose (International Music Company, 1952). ↵

- Becker's note: "The solo part contains a number of changes that differ from how they appear in the full score and in the piano reduction. These changes represent concessions for easier playability. Most of them involve bowings, for example, on the fourth beats of the two double-stopped measures on the first system of p. 15 and on the second and fourth beats of the first bar of the second system. Here, too, I prefer the original version, which goes like this:

However, it does require greater bowing skill." ↵

However, it does require greater bowing skill." ↵ - Becker's note: "See the section on portamento." ↵

- Becker's note: "One should forgive the small correction of a possible error of notation. A claim by Rubinstein states: 'One should not play the obvious mistakes so accurately that one even plays along with the printing errors.' See the section of this book on artistic liberties." ↵

- Becker uses the expression nationaler Charakterisierung, referring to the Romantic Nationalist interest in folk songs. ↵

- Becker's note: "See the section on artistic liberties." ↵