Lecture-Analysis: Haydn, Concerto in D major

Allegro moderato, M. M. eighth note = 104-108

Before players can approach an interpretation of a piece, they should gain an understanding of the character and mood of the composition. In the Haydn Concerto, the first movement is characterized by cheerfulness and vitality, the second movement fulfills an intimate mood, while the last movement is marked by spiritedness and bubbling humor. —Of course, these fundamental traits do not exclude occasional contrasting episodes, which in the first movement even rise from the lyrical to the dramatic. It is precisely in this that the mastery of the composer shows itself, in bringing the basic idea to special prominence through appropriate contrasts, without detracting from the unified mood of the piece.

With regard to the aforementioned fundamental character of the first movement, the player should therefore refrain from excessive sentimentality!

Apart from the often observable erroneous conception in this direction, the player is prone to a number of other mistakes that, however, result from technical deficiencies.

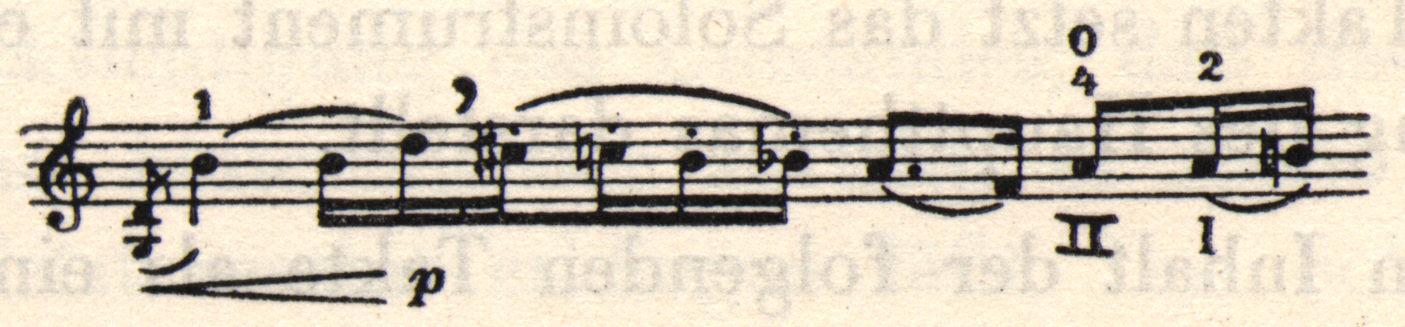

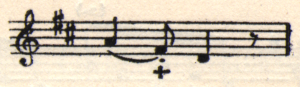

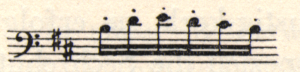

The very first measure usually lacks the necessary precision, mostly due to incorrect accentuation, and often also due to deficient rhythm:

Only the first and third of the group of four sixteenth notes should have agogic accents. The last sixteenth note of the measure (i.e. the F-sharp) is usually incorrectly shortened, so much so that some players make it sound like a thirty-second note.

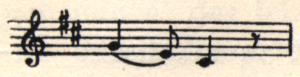

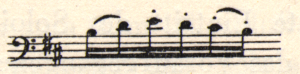

In the second measure:

players often lack the necessary gracefulness.

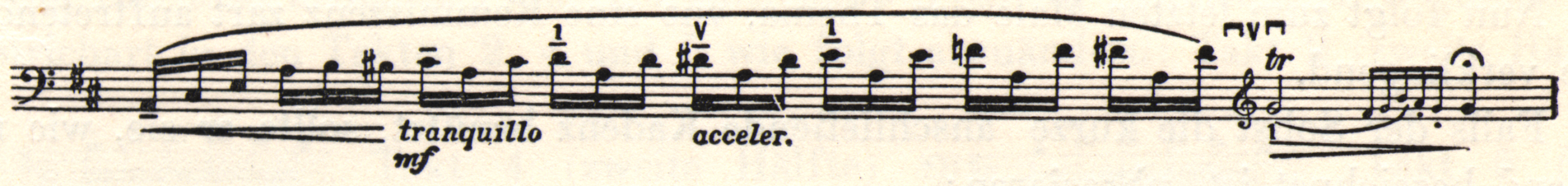

The best solution—let the player try it out[1]—consists in: crescendo on B; land on D piano; take a small “breath,”[2] then gradually accelerate up until this motive:

where the first A should receive the emphasis. The four sixteenth notes that follow D in the sextuplet should be taken in one bow, with soft staccato!

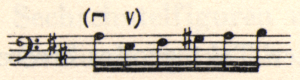

In the fifth measure after rehearsal B,[3] second quarter beat of the measure, the agogic emphasis should be on the first E:

Avoiding noticeable portamenti, simply play through the passage!

On the second measure after rehearsal C, use a long up-bow! On the fourth measure after C, delay the two notes D and F-sharp (located on the first part of the first quarter beat of the measure), then make up for the delay in the second part of the beat! The same applies to the figure when it appears on the third quarter beat of this measure.

At rehearsal D: the first measure of this solo should be played in a slightly archaic, formal style; play the repetition of this figure on the third measure more gracefully in a piano dynamic. Shortly before the beginning of the D major scale, add a crescendo; don’t rush through the octaves passage, so that the conclusion of the phrase will sound calm and grand!

At rehearsal E: the second theme begins in a cheerful spirit, joyfully animated. When the theme repeats up an octave, intensify the dynamics!

Two measures before rehearsal F: make a delay as you begin the thirty-second note figures, and catch up through accelerando! One measure before F, separate the first sixteenth note from the second on the second beat of the measure, for the sake of good phrasing!

The passagework of the transitional section should constantly intensify in dynamics up to the measure of the fermata. Despite the position shifts, we should not be able to hear a portamento. Following this is a shorter episode, whose melodic material is derived from an inversion of the first theme (page 6, third system, first and second measures). This leads to the development section.

During the repetition (in the two measures that follow), playing the melody somewhat more expressively would not detract from the charm. As we get further into it, it tightens up and develops ever greater energy.

The orchestral introduction to the development section brings renewed dynamic intensification to the main theme. Six measures in, the solo instrument enters with a motive that again represents the inversion of the main theme.

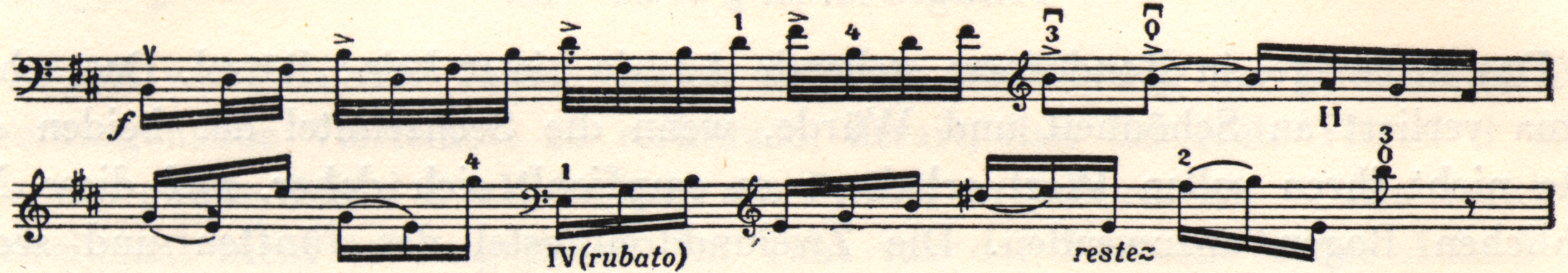

We may imagine the content of the measures that follow as a dialogue, in which lyrical tenderness alternates with dramatic decisiveness. To make the sextuplets more interesting and give them prominence in the dialogue, we should try (while favoring the bass notes in the voice-leading) to begin in a rather mysterious mood, and build to an ominous, menacing one over the course of the next two measures.

At this energetic entrance of the orchestra, this figure (page 7, last measure, seventh system):

sounds like a pleading response seeking reconciliation. It must be expressed with the most tender tone.

The episode in B minor that begins at rehearsal G presents a dramatic scene. For the sake of brevity, this passage is described in more detail below:

The next two measures should likewise be presented in this way. After four measures, a soulful transformation begins. Now, the tenderness of the initial lyrical, gentle character transforms gradually into heroic strength.

The three measures before rehearsal H sound like a fierce struggle that uses all available energy, reaching its climax in the last measure.

At the beginning of rehearsal H, eight sixteenth notes in the orchestral part lead us from this heated fight into rest and composure. A more reconciling mood takes over; interrupted, however, by several more dramatic incidents, and the back-and-forth continues until the orchestral tutti at rehearsal I. The second theme now appears in D major and should be played in the same manner as in the exposition, as should the group of figures that follows!

This measure is very important; it must be played very freely (like a cadenza!). It leads into the part that precedes the cadenza, in some extent as a preparation for it.

To execute this episode compellingly, note that the orchestra presents the motive from the first theme three times in succession—first tender and hesitant, then somewhat more decisive, and finally resolute. The solo cello responds each time with a thirty-second note figure, which concludes with a reminiscence from the third measure of the second theme. Here, the first half of the theme is always playful, the second more expressive but always more intense, so that the theme as a whole builds to a climax on the D major sixth chord and the measure after it. (Page 11, third system, second measure.)

The movement now continues with greater energy and triumphant joy up to the cadenza. In the penultimate measure (p. 11, fourth system, second measure) the following alternative may be chosen:[4]

Adagio, M. M. eighth note = 66-69.

This song-like Adagio in rondo form presents no puzzles. The simple theme loses beauty and dignity if the sixteenth notes of the first two measures do not receive their full value; therefore, we recommend generous amounts of bow. The thirty-second notes of the fifth and sixth measures should be played rubato!

The next episode after the restatement of the theme by the orchestra should not be played mezzo-forte, but rather should begin in piano and have a heartfelt, touchingly naïve expression—like Mozart’s The Violet.[5] (The appoggiatura in the first measure should be longer.)[6]

Gradually the expression increases and demands greater intensity, reaching a high point on the measure of the fermata. This measure provides the transition to the closing theme, so the thirty-second notes must not be “sung” as in a passage, but rather “declaimed.”

The C major episode that follows this requires a slight acceleration of tempo and a certain seriousness in expression. From the seventh measure onward, the tempo presses on toward the E with a fermata on it. The cadenza-like group of notes that leads to the main theme should also be declamatory (and rubato!)

Next, the theme appears for the last time, in the manner of a reminiscence that emerges tenderly and lightly fades away.

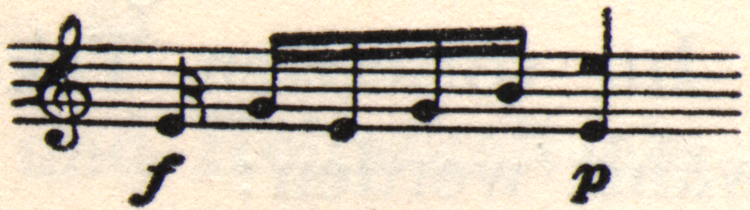

If the soloist uses the short connecting cadenza, the phrasing should go as indicated:

Allegro, M.M. dotted quarter = 84

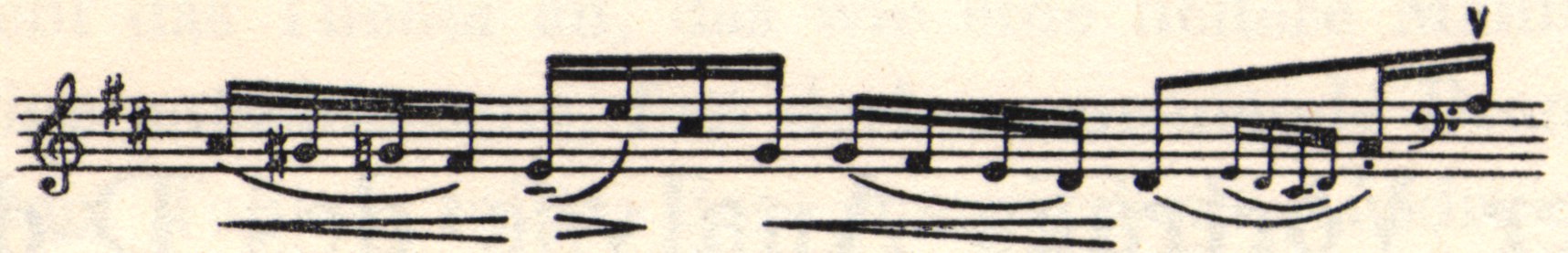

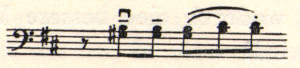

The main theme enters with vigor, joy, and cheerfulness. It must be crisply rhythmic, though without rushing in measures 2 and 4. For refinement, separate the third eighth note of measure 2—that is, lift the bow after the first quarter note, like this:

but slur it beautifully in the fourth measure, with a slight diminuendo!

In the next four measures, for better articulation of the notes marked with staccato dots, the preceding quarter note should be shortened so that the first quarter note (D) is taken at the tip, and the second eighth note (D) is like an upbeat at the frog. — Don’t shorten it as much the next time! In the measure before the fermata, it is better to slur the final eighth note in! — So that the fermata doesn’t interrupt the flow of the phrase, one should imagine (while playing the fermata) the continuation of the eighth-note motion under a moderate ritardando. This will achieve better connection with the orchestral entrance that comes right after this.

At the soloist’s second entrance, “dolce” should not be confused with “saccharine.” It can have a sense of humor. We can achieve this by shortening the first note (E) and accentuating the G in the second measure, as well as by joining the first three eighth notes of the third measure under the same bow direction.

Conversely, the fourth eighth note must be somewhat broader, in order to slightly accelerate the sixteenth notes that come after it. In and after the sixth measure, place agogic accents (“Abzüge”)[7] on the first eighth note of each pair of slurred notes, and dot the third!

The following brilliant figure at rehearsal A should begin on an up-bow, and the bowings in the second, fourth, and fifth measures of A should be changed as follows.

Rehearsal A, second measure (second half):

Rehearsal A, fourth measure (second half):

Rehearsal A, fifth measure (first half):

In the measure before the fermata, don’t use a lot of bow on either of the A quarter notes, so that the return to the frog doesn’t sound too harsh; surging[8] sounds should be avoided. Handle the fermata measure in the same way as before, so that the connection can go smoothly. For the next entrance, use the following bowing:

The third-to-last and penultimate measures before rehearsal B are notoriously awkward for the fingers of the left hand:

It is quite possible that players who place accents here started doing so not for musical reasons, but mechanical ones (such as awkward use of the bow) We would prefer to follow more musical intentions. Emphasize the bass notes so that you can toss off the high ones more lightly.

Measures 2-5 of rehearsal B should be warm and singing, and the next four measures should have a certain graceful boldness. The second and third eighth notes of the second measure after B should taken under one bow, and sound singing.

Here is the bowing for the fourth measure after B:

Rehearsal C: the first four measures are very energetic, measured, and strong. They should sound rhythmically precise, without any change in the tempo. The subsequent two measures should, again, sound singing! At the repeat of this figure, play using a slight echo effect and crescendo up to the trill at rehearsal D!

In the fourth and sixth measures after rehearsal D, the eighth notes are the melodically significant voice of the two. This melodic line extends all the way to the first sixteenth note of the next measure, which should be played rather calmly, whereupon a slight accelerando can compensate for the delay. The sixteenth-note groups are to be played more softly (starting from the third sixteenth note) than the eighth notes.

From the eighth bar of rehearsal D onward, the expression should become gradually more energetic. Do not linger too long on the high A, and do not make an excessive ritenuto!

The next entrance of the soloist should return to the playful, bold manner, as if making ironic fun of what has occurred before. The sixteenth notes should be played spiccato.

One measure before the fermata, calmando! In the fermata measure, we must hold a strong crescendo from the note A up to the B. We should also hold onto the B so that it sounds like a sigh before we decide to resume the tempo. There should be a big diminuendo on the B. — A short G serves as a kind of upbeat to what comes next!

There is nothing particular to note about the slight variation of the theme that now occurs. When it appears in “minore,” however, the performance is more emotional, beginning with a slightly sorrowful, almost sulky tone.

The shift to the minor mode encourages the interpreter to take the tempo a little more calmly for a few measures, then, in the second half of the eighth measure, the sixteenth-note figure in the orchestra begins again with passage in octaves at the old tempo; this requires spirited execution.

Now we reach an episode featuring new material in F major. This is somewhat in the style of a hunting song, and requires humor and rhythmic execution. It alternates with the passage in octaves mentioned above, and creates a kind if interplay between carefree playfulness and a more menacing seriousness.

Note: be sure that position shifts are inaudible in the octaves passages—no portamenti! In the first measures, give dynamic preference to the notes on the C-string, then (when the passage goes up the octave) the notes on the D-string. Play with robust strength!

The second repetition of the passage in octaves leads into the cadenza. Make sure to hold the last A, which connects the two sections, for a long time!

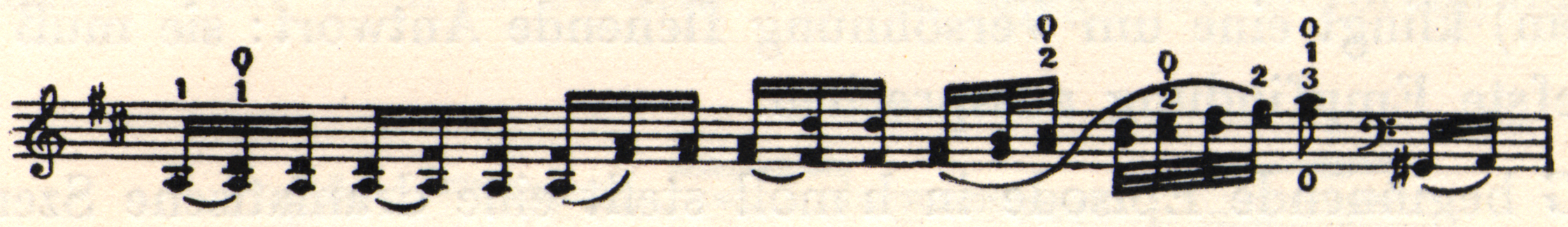

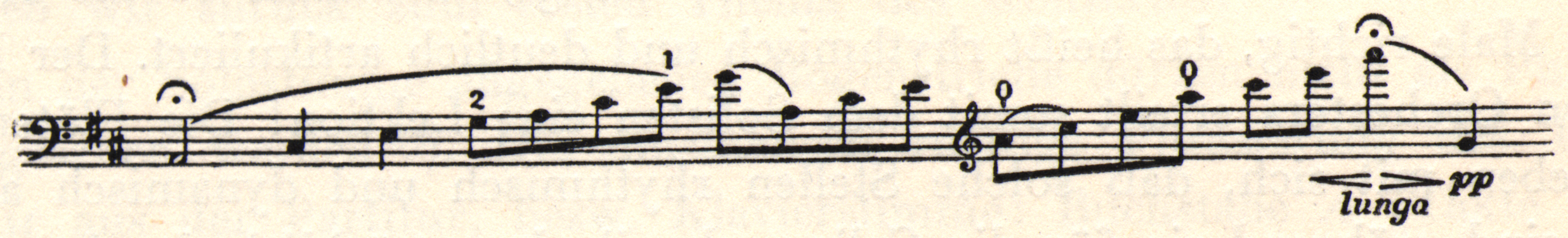

The rather successful short cadenza by Gevaert, which takes place over an A pedal, should begin calmly, almost as if improvised. Enter tenderly! In the second half of the second measure, stretch out the motive G-E and play more softly, and do the same on the A in the fourth measure (for an echo effect)!

From the fifth measure of the cadenza, begin slowly at mezzo-forte, then gradually get faster, letting it fade like a question! In the same manner, the sixteenth notes should be played using the open A-string for the sake of dynamics. This gives the impression that the note keeps going without interruption. Always give the agogic emphasis to the first note of the second half of each measure!

Let the descending motion of the eighth notes gradually die away, so that the thematic motive fades away into the greatest calm and tenderness. In place of the chromatic scale, the following variant appears:

We may produce an excellent effect through an approach where we introduce the main theme (returning here for the final time after the cadenza) in a poetic manner, gently and calmly, evoking sweet memories of the past. However, this applies only to the first four measures, because from the fifth measure onward the tempo gains new life.

The orchestra leads the theme forward in a jubilant manner, while the solo instrument plays around it in brilliant sixteenth-note figures.

Finally, we should point out that often, the choice of a too-fast tempo unfortunately spoils the graceful, charming character of this movement. “Temperament” and “bravura” are out of place here! Instead, the performer should strive to bring out every nuance of gracefulness and good humor with refinement and sensitivity. Unhurried cheerfulness, not hasty execution!

This work has undergone many revisions and been published in various editions. The version by Gevaert that we have presented here is a fortunate one. Since our analysis is based on this version, the suggested modifications should not be regarded as deviations from the composer’s original, nor as violations of the fundamental principles of the notated text.

- Becker uses the German expression der Spieler möge sich selbst davon überzeugen, literally "let the player convince themselves." In other words, Becker tells the player not to take him at his word, but try out his advice as proof that it is the best solution. ↵

- Becker uses the German musical term Luftpause, "breathing space." ↵

- The score to which Becker refers in this chapter is Robert Schwalm's 1915 edition (with fingerings, bowings, and cadenzas by Becker) of an arrangement of Haydn's Concerto in D major by Adrien-François Servais (1807-1866) and François-Auguste Gevaert (1828-1908). This arrangement, which made significant cuts and revisions to the work, was the version of choice for most cellists in the first half of the twentieth century, after which it gradually fell out of fashion. ↵

- Becker's note: "Cellists who desire a more thematically developed cadenza should refer to that by the present author, which is included in the edition of the Haydn concerto edited by [Robert] Schwalm and published by Steingräber. In this edition, the present author is only responsible for the fingerings, bowings, and the two cadenzas. The wording on the title page: 'Edited by Robert Schwalm and Hugo Becker' is therefore incorrect and was published—probably by mistake—against the express wishes of the latter." ↵

- Mozart, Das Veilchen ("The Violet"), K. 476, for voice and piano. ↵

- Becker's note: "See the essay on appoggiaturas." ↵

- Becker's note: "See C. P. E. Bach, Quantz, and others." ↵

- Becker uses the German expression herausgehämmert, "hammered out." ↵