Lecture-Analysis: Saint-Saëns, Concerto in A minor, Op. 33

Saint-Saëns’s Cello Concerto is often underestimated in terms of difficulty. In some circles, there are those who do not consider it challenging to perform the work publicly.

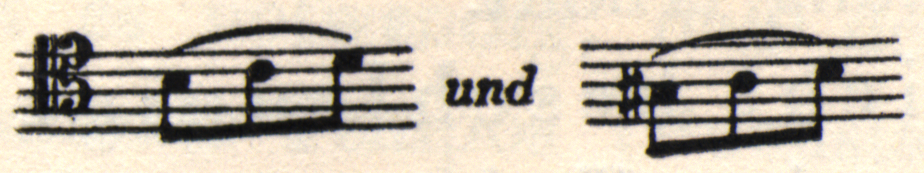

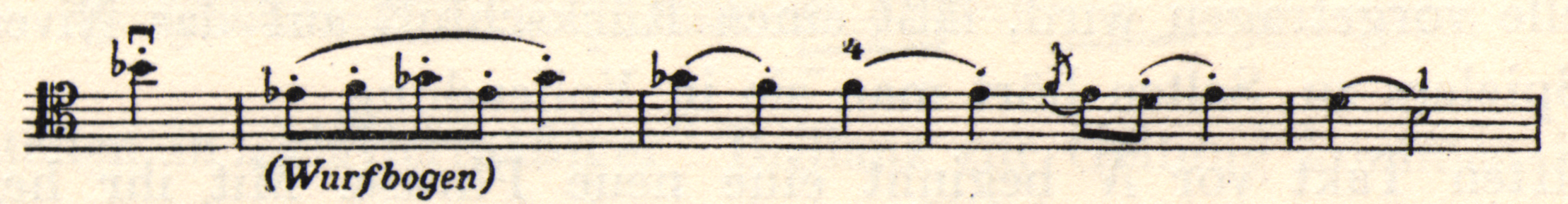

To be sure, it is not one of the most difficult cello concertos. However, it contains a number of passages that one almost never hears played completely right! The difficulty begins with the very first theme:

We most often hear it unrhythmically and indistinctly played. It is only when the flute enters with the theme in the first tutti section that we get to hear it correctly—that is, rhythmically and clearly articulated. The orchestral flutist teaches the soloist a lesson! The mechanism of the flute makes it relatively easy to play passages like this rhythmically and dynamically cleanly, whereas for cello technique—mainly because of the position shifts—they pose some difficulty.

To solve this problem of clear diction once and for all, it is essential for every cellist to become familiar with the general musical rules and principles of performance, then to learn learn to recognize the specific difficulties of the instrument and compensate for them through intelligence study.

Such difficulty consists, for example, in playing a series of notes in a rhythmically and dynamically even, legato manner (as pianists learn to do in their first six months of study).

No player can escape the need to train themselves (or be trained) in playing objectively. Even with the highest natural talent and technical skill, a performance lacking in objective clarity will leave the discerning listener feeling artistically unsatisfied.

In this particular case, we will first examine an error we commonly hear in performance: that the cellist does not really feel the rhythm of the opening theme. This rhythm consists of a combination of quarter notes and triplet movement. The player must already “feel” the eighth-note triplet subdivision of the beat during the rest on the first quarter beat of the A minor chord in the orchestra, and during the first E (i.e. the first note of the theme). Only by doing this can they smoothly connect the run of notes that occurs after that first note.

Furthermore, the fingers of the left hand tend to rush during these ascending passages:

We can control this tendency by taking care to lift the non-playing fingers.

Another cause of imprecision is playing the regular eighth-note A too short after the run of triplets (second measure, third quarter beat).

Anyone who takes such matters lightly, and who thinks the demand for the utmost rhythmic precision is pedantry, is beyond help. Perhaps I can still convince them with this piece of advice: that a soloist who plays rhythmically carelessly deprives themselves of one of the strongest effects. If we read analytical works of past epochs, such as Quantz’s famous essay On Playing the Flute, we could easily dismiss the concerns of musicians of that time as pedantry. Modern musicians have reacted against this by seeking rhythmic freedom, but go too far in the opposite direction. Perhaps as a result of modern living conditions, we tend too much toward haste. Restless improvisation often takes the place of measured, conscientious work. In most cases, precisely observing the composer’s instructions would prevent such gaffes.

Let us return to the first theme of the concerto!

The bowings indicated in the solo part must not be regarded as phrasing marks.[1] We can glean the musically correct phrasing of the theme from the full score (or the piano part)[2] at rehearsal A (i.e. measures 24-26 of the piece).

From this, it stands to reason that the bow change must be imperceptible, so that we do not destroy the unity of the phrase. Given this, it would make no sense to change the bow direction on the second beat, as some cellists tend to do, believing that the eighth-note E should be slurred into the following quarter-note F (as it is in the following measure, 3, down an octave).

In measure 3, it makes sense, because this repetition is preceded by a pause. In the preceding measure, however, this phrasing would make the note that enters on the strong beat sound shortened, and this would be incorrect. The transition of the triplet figure into ordinary eighth notes (measure 13 and 14) should occur without any rhythmic alteration. (Ample movement of the upper arm is necessary in measure 14!)

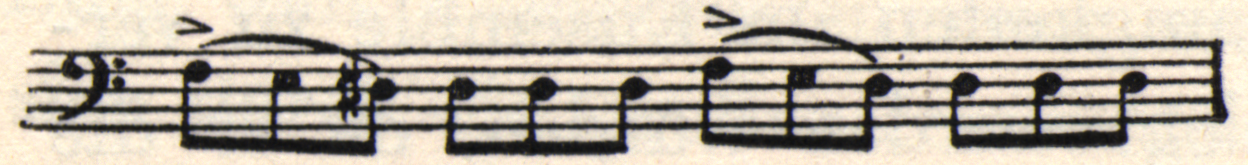

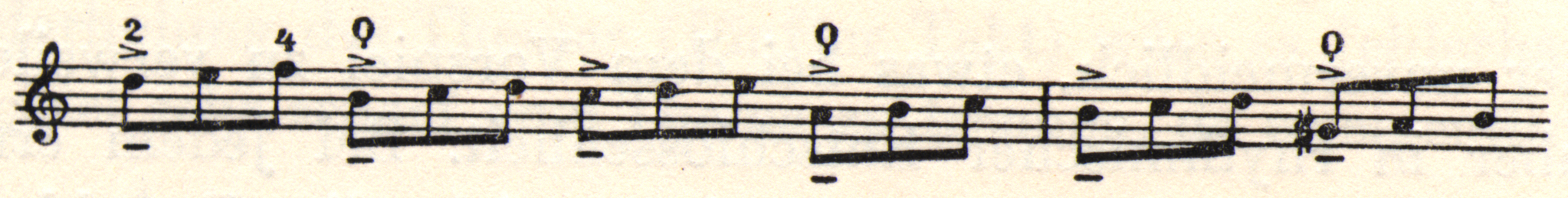

To support the dynamic increase in the triplet figure that begins at “Poco animato,” we recommend starting piano from the second triplet eighth note (i.e. the first G-sharp). The marks >> in measure 17 should not be interpreted as jolting accents, but rather as small tenuto articulations on this motive:

The next time we have three D-sharp eighth notes a few measures later, these accent marks are omitted. In this way, this repetitive half-bar phrase takes on an insistent, pleading character, which increases its effect.

Measures 20 to 24 (four before rehearsal A) must not be accelerated (unlike the analogous passages four bars before C, which we will discuss later), because they lead back to the tempo primo in the “Poco animato” (measure 16) via the short, slight rallentando. From rehearsal B on, play with strength and great rhythmic strictness! In the second measure of B, again be conscientious when going from triplet eighths to normal ones. Particular care necessary to take enough time over the first eighth note on the third beat of this measure.

The chromatic scale—rehearsal B, eleventh and twelfth measures—must stay strictly in time with the orchestra when they bring in the theme. For coloristic reasons, namely so that you can begin the second theme (rehearsal B, measure 17) on the D-string, you should also use the D-string and not the A-string for the chromatic scale. The open A-string should be treated discreetly so that it does not sound out from the notes on either side of it. You can reach this goal through differentiating the amount of force you use in bow pressure. It is common to hear problematic use of agogics in the last two measures leading into the second theme. First is the introduction of a big unmarked rallentando, which causes the soloist to play the second them (beginning in the seventeenth measure of rehearsal B) too slowly. Secondly, an illogical execution of the diminuendo. One should not rush into the second theme, however; rather, in addition to the strictly logical diminuendo, there should be a small calando in the last four eighth notes. This way, the last eighth note is actually the softest and longest of the four. This measure presents some difficulties for many players, since the diminuendo and calando occur on an up-bow!

The second theme, through its somewhat uniform movement, creates the danger of monotony if we do not declaim it with a certain freedom. It is therefore a good idea to play the third and fourth measures rubato, so that of the eight quarter notes, the first two and last two are somewhat calmer. The middle ones need to be a little more urgent. However, we must not let this in the slightest alter the total rhythmic value of both measures.

As far as the second theme itself is concerned, it is usually played not just too slowly, but also too heavily. There is no evidence for doing this. The composer’s instructions are quite the opposite. When the orchestra returns with the first theme, it is important to avoid inaccuracies in the ensemble, which, incidentally, would always be blamed on the soloist, since they are the one leading the piece!

Next, the triplet passage in G minor (twelve measures before C) should be played in an analogous way to the first time this figure occurred (eight measures before A, in E major).

To structure the next passage logically (starting at the eighth measure before rehearsal C), the player needs to determine from the outside how fast they will play the Animato at rehearsal C. The accelerando must be distributed over the eight bars in such a way that it actually forms a transition to the animato. Only with this may the maximum speed be achieved. The excessive accelerando that we often hear has the unintended effect of turning the Animato into a “Più tranquillo”!…

The two forte measures at rehearsal C should have a broad off-the-string stroke (martelé-détaché); then, at the piano dynamic, should immediately change to spiccato at the tip.

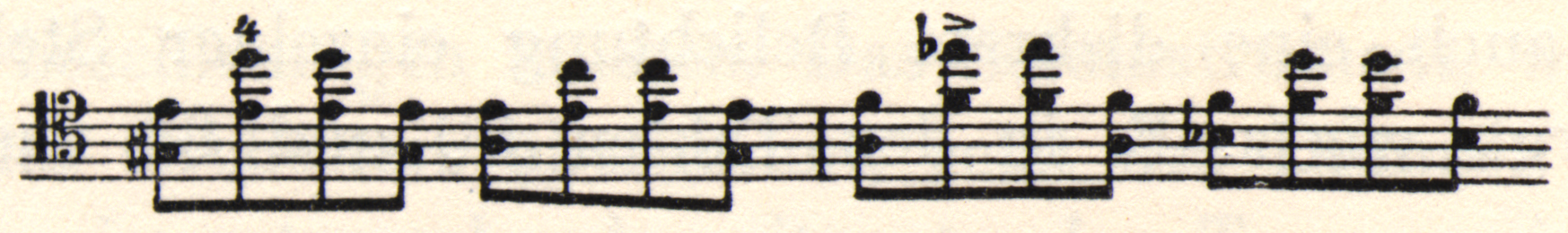

At the ninth measure of C, we should emphasize the harmonic progressions that fall on the strong beats. The great nineteenth-century master Cossmann[3] used to substitute some slight modifications for the fifths and sevenths in measures 11-12 of C:[4]

We cannot recommend these too highly, since, apart from the greater ease of intonation, the passage gains some harmonic appeal. For the sake of greater clarity, and to avoid audible position shifts, we should emphasize the strong beats of the measure.

The measure before the Allegro molto must not have a ritenuto, as so often happens! The tempo has actually been increasing since eight measures before rehearsal C, and which leads into the Allegro molto. The Tempo primo only resumes at rehearsal D.

The main theme, which now appears in D major, is now somewhat more contemplative. — In the eighth measure of rehearsal D, there begins an interplay between the orchestra and soloist; it requires fine shading if the passage is not to become tiresome. There is no need to give precise instructions about taking individual liberties in agogic and dynamic terms, since the judicious use of light and shade is left to the player. At the end, when the arpeggios begin, there should be an extensive crescendo and great liveliness!

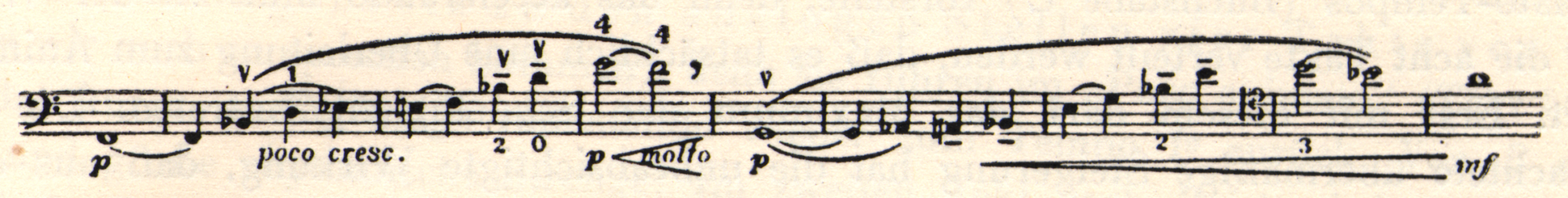

At rehearsal E, there is a very energetic, almost dramatic entry; again, in the fourth measure, we have diminuendo and calando!

From the seventh measure of the theme (which one ought to play exactly as it was when it first appeared), the expression should rise to ever greater intensity, building up to the high B-flat. At the F in the seventeenth measure after rehearsal E, however, the intensity lessens so that it can rise again anew at the ascending quarter-note figure.

A very beautiful effect, though not specified by the composer, can be achieved with a big crescendo on the two half notes; followed by a “breath” and the entry at a piano dynamic at rehearsal G.

Then, however, the ascending line increases in power as before. This time, we stay a little longer at the top of the melodic line, then gradually decrease the dynamic from the fourth measure before rehearsal F until the resolution.

At rehearsal F, the middle movement “Allegretto con moto” begins. It sounds like a tender minuet resonating in the distance. After 33 measures (and without allowing the slightest slowing of tempo by the orchestra in the thirty-second measure!) the solo cello enters with a melodic counterpoint to the theme, in the character of a lovely pastoral melody “pianissimo dolce assai.”

Any pathos, any stronger emphasis in tone and expression should be avoided! Even if a discreet lightening of individual notes provides some temporary animation (as for example in measures 60 and 61 after rehearsal F), there should at no point be any stronger contrasts.

When playing these two measures, we can achieve a gentle echo effect through the finest dynamic shading. Two bars later, the expression (note: the dynamic is piano, according to the composer’s instructions!) begins to rise somewhat, as if the distant music were being carried closer to us.

Now, a short cadenza interrupts the middle movement. The ascending eighth-note figure should be played without altering the rhythm the first time, but when it repeats up an octave it should have a slight ritenuto so that the note D is a fermata and a point of repose from which the new material begins. These two measures are best played like this:

Next comes the descending eighth-note triplet figure. This should start slowly, with slurs of three notes, but as the accelerando increases the bowing must transition into a ricochet arpeggio stroke (which is not to everyone’s taste!)

It should be played slowly at first, tied in three notes at a time; but gradually, with the accelerando increasing, it must transition into the jumping arpeggio stroke (which not everyone can do!), emphasizing the chromatic voice-leading in the upper voice. —The off-the-string stroke should develop naturally out of the legato bow stroke. —A slight diminuendo begins in the middle of the arpeggio figure, followed by a slight calmando towards the end. To execute an effective fermata trill on D, use two bow strokes for the swell and only one for the fall. However, the duration should be the same for both crescendo and diminuendo.

Continuing: take the sequence of trills on E-flat, E, and F in one up-bow! Then, on F, place a light accent at the beginning of the measure (rehearsal G), so that the orchestra gets a secure cue for the entrance. The sequence of trills should experience no interruption; the trilling finger should not stop its motion during the position shifts. At the end of the trill, on the note B-flat, begin the sixteenth-note figure slowly and increase the tempo in such a way that the last group is the fastest and acts as an upbeat to what follows. The shortest note of the four sixteenth notes is the very last, the longest the first! Furthermore, every first note of each group should be emphasized.

Measure 29 of G, and the measures after it, have an urgent quality, so we must slightly accelerate the tempo. The solo instrument, which takes over this driving eighth-note movement from the orchestra, continues this movement until the fourth measure, in which a corresponding ritenuto restores the tempo for the reappearance of the orchestra’s thematic motive four measures later. The following passage should be modified as follows in order to achieve the most graceful design possible in terms of bow technique:

Five measures later, do the same. —The middle movement closes in the same rhythmically strict manner as it began.

At rehearsal H, the first theme from the first movement comes back in the orchestra, initially timidly introduced in piano. The solo instrument takes over once again, in a passage similar to that at rehearsal B. Here too, it should be rhythmically tight, with a powerful tone. This character is continued by the orchestra, so that the entire passage creates an effective contrast to the final movement that is about to start.

At rehearsal K, the direction is “Un peu moins vite”! Despite this instruction, people usually take this tempo far too slowly, causing the beautiful theme to lose some of its grace and lightness. With this melody there comes a danger of rhythmic distortion, as players tend mistakenly to emphasize the quarter note as if it were the strong beat of the measure. We can avoid this by applying a slight tenuto and increased vibrato to the first eighth note, and perhaps adding a slight diminuendo from the eighth note to the quarter note. — In the fourth measure, place a small crescendo to the first quarter beat of the following measure! This should decrease on the first two quarter beats of the fifth bar! Begin a dynamic increase starting from the fourth quarter beat of the seventh bar of K, continue to the beginning of the long E (eleven bars after K), then decrease to pianissimo at the resumption of the theme. This time, however, the theme should develop in an even more significant crescendo which reaches its climax in the penultimate and final measures. On the seventh and eighth measures before rehearsal L, play with greater urgency until the first triplet note of the next measure!

It is advisable to play this measure with rubato, and to proceed in a way that allows one to place a small “breath” before entering after the first quarter note [of the sixth measure before rehearsal L]. The broken A minor triad should begin quite slowly, then catch up with the delay through a strong acceleration in the second half of the measure. Observe the beat strictly!

On the whole, the last three or four bars of this section should create an impression of drama, because the subsequent development is very excited.

Beginning at rehearsal L, the sixteenth-note passage is not always played faultlessly; make sure to use the greatest clarity and evenness, in connection with strict rhythm!

In the two measures after rehearsal L, there should be small accents on each sixteenth-note group! Do the same the second time (nine after L)!

Eight measures before rehearsal M, shape the figure in a way that emphasizes only the first two of every eight sixteenth notes, and play the subsequent six notes with very little bow, in a piano dynamic. — The composer wrote slurs over the sixteenth notes in the third measure of M, but these are generally played separate, with a spiccato stroke, which is undoubtedly more reasonable. It is also advisable to place a strong emphasis on the first of every four sixteenth notes. The way this passage is performed gives an indication of the player’s bowing technique. One rarely hears this performed perfectly.

Twelve measures before rehearsal N, a new phrase begins. With it begins the most passionate part of the entire piece. This passage is powerful and spirited, and should be played with good accents; so should the analogous measures after the two scale runs. The passage gains liveliness and grandeur when there is a rubato over the three measures. This should begin slowly, become faster in the middle, and broaden again at the end.

As for the scale runs, they can only be heard effectively if we split up the bow, as indicated here:

However, taking this liberty in bow technique should not interrupt the natural flow of the run.

In the octaves passage, avoid audible position shifts by reducing bow pressure. On the descending octaves passage, there should be an accent on the first of every four. The player should differentiate clearly between whole and half steps!

The partial scale figures in the sixth and seventh measures before rehearsal O cause difficulties for many players because it is hard to achieve clarity on the C-string. An unintentionally grotesque effect often occurs; we can easily avoid this by using all the bow-hair on the string and choosing a sounding point close to the fingerboard. The left hand performs the change of position very suddenly! The player should imagine that he wants to execute the accent with the left hand alone; the suddenness of the movement of the left hand then transfers itself reflexively to the bow arm—a phenomenon that we otherwise try to avoid, but use deliberately here for artistic reasons.

At rehearsal O, play with a full, beautiful tone on all the hair; however, the tempo should not be slower than before! In the third measure after O, do not play portamento from F to A, but rather from A to C. This lyrical section closes with an ascending passage for the solo instrument, which displays the entire range of the instrument (over five and a half octaves)!

We have discussed all essentials for the material between the end of this section and rehearsal R, so this requires no further explanation. The only exceptions are the sixteenth-note figure beginning 34 measures before rehearsal P:

and the subsequent passage in eighth-note triplets:

To ensure these passages come across with a brilliance comparable to that of a piano, ensure that you play with the greatest consistency in rhythm and dynamics. Use more bow on the accented notes!

Following the above instructions for fingering, bowing, and dynamics (including accents!) will contribute significantly to success.

Do not take the tempo of the coda (which starts at rehearsal R) too fast, as the build-up should keep the listener in suspense up until the end.

The custom of playing the eighth-note figure in octaves starting from the B of the last bar of the penultimate system should not be rejected.

- Becker's note: "See my essay, 'On the Meaning of Slurs.'" ↵

- Becker's note: "Since not every cellist owns a [full orchestral] score, this analysis was based on the piano reduction." ↵

- Bernhard Cossmann (1822-1910), the German cellist, composer, and pedagogue who served as a professor at the Moscow Conservatory and later the Hoch Conservatory in Frankfurt. ↵

- Becker's note: "See the section on artistic liberties." ↵