Off-the-String Strokes

Off-the-string strokes, with all their possibilities for dynamic gradation and tonal shading, are an outstanding means of expression in cello playing.

By using the various types of off-the-string strokes—a broader stroke that is more akin to détaché, or a lively, crisp, yet resonant projecting spiccato—it is possible to bring an expressive range into the performance that is entirely equal to that of the violin, provided that the left hand’s agility does not lag behind the bowing technique.

We cannot master off-the-string strokes just by swinging and shaking the bow around and leaving the outcome of tone quality and speed solely to the elasticity of the bow stick—and to chance.

Elasticity is just one factor in off-the-string strokes. There are a number of other factors involved, such as the choice of sounding point, the tilt of the bow, and the how we regulate our physiological forces.

In this chapter, we will discuss off-the string and ricochet (“thrown”) strokes together, since there is no clear boundary between the two. The distinction is that one can “throw” the bow in a ricochet stroke at any point within the elastic range of the bow and at adjustable speeds; whereas true spiccato is best performed at a specific point on the bow near the balance point (i.e. between the balance point and the middle of the stick) and only within certain speed limitations. In contrast to the true spiccato, there is also a modified off-the-string stroke.

When performing spiccato at a fast tempo, we primarily depend on the elasticity of the bow and string. Therefore, the most suitable part of the bow to use is the area near the balance point. For reasons we will discuss later, it is important to be able to reduce the activity of the hand and forearm as much as possible, so that the bow can come off the string freely without interference from the fingers.

To achieve this minimal action, we must relax the shoulder and let the whole arm work together as one loose, swinging unit. The arm creates the motion, but the fingers and wrist actively help by flexibly adjusting and controlling the stroke, including changing the speed when needed. Off-the string strokes are not just one uniform, fixed, unchangeable technique, as some schools teach. We can vary how we do it by regulating the sounding point, bow tilt, bow pressure, and force of the arm. The expressive range of off-the-string strokes has many possibilities, and does not only extend to virtuoso showpieces such as Dance of the Elves, At the Fountain, etc.[1]

The fundamental spiccato movement

The fundamental spiccato technique, which is common to all its variants, consists of two movements: a “striking” of the bow onto the string (to enable it to bounce off the string) and a brief stroke along the string (to produce tone).

The first component is best described as letting the bow fall onto the string through a double-lever action of the fingers, without any significant change in the wrist (see images 55 and 56 of the Appendix). The second component consists of a short up-and-down bowstroke, which is performed using a movement similar to the grip change technique.

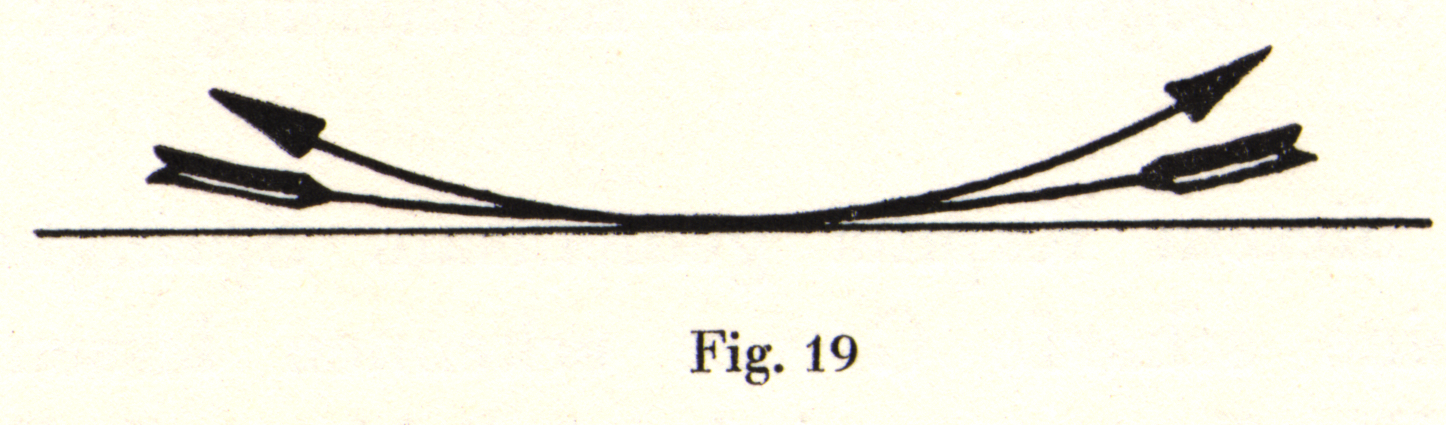

The unified spiccato movement, which combines these two forms of motion, resembles (in outward appearance) the descent and ascent of a seagull that skims over the water surface, catching its prey in flight (Fig. 19).

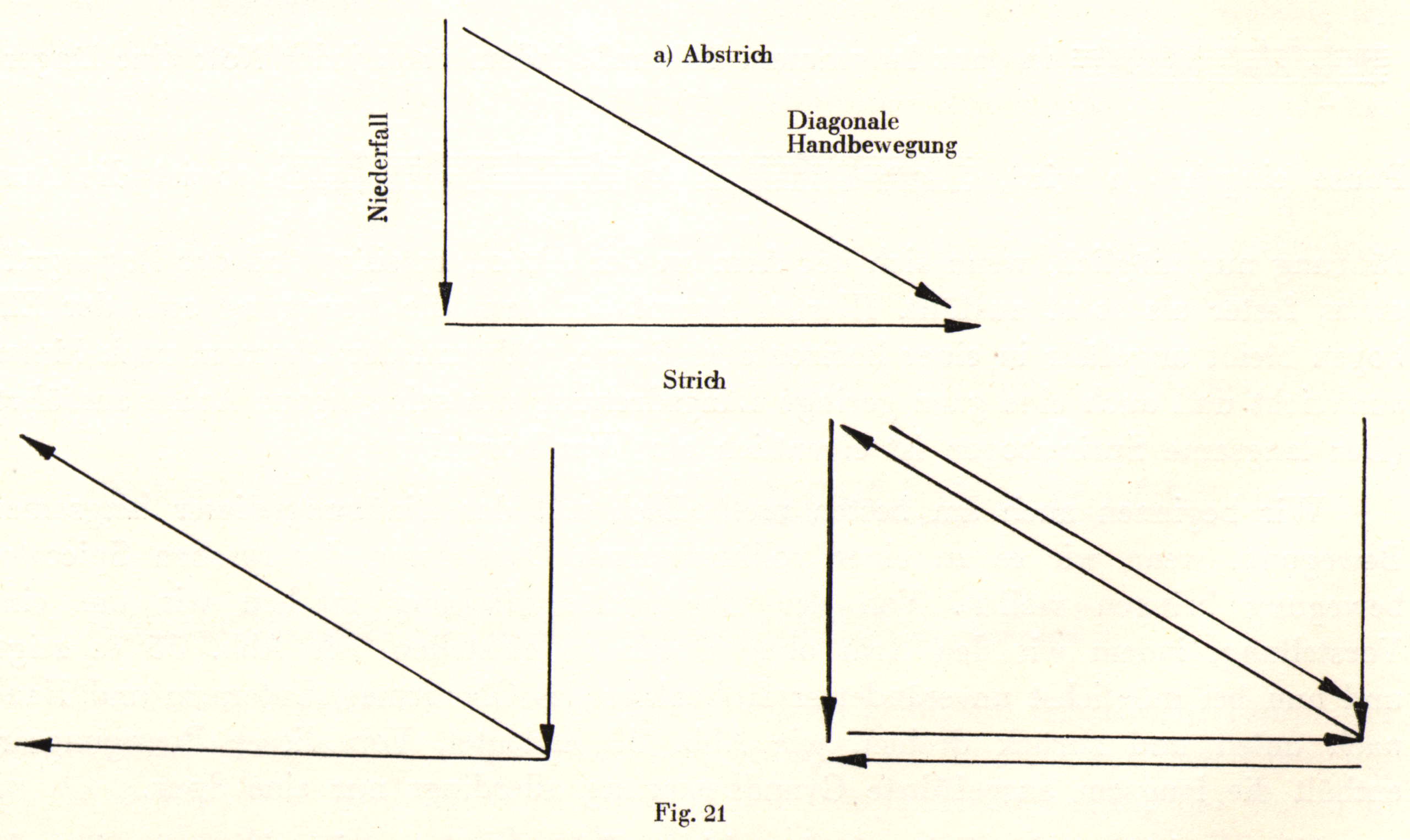

The “beating” is combined with the stroke. The movement goes in a diagonal direction, as demonstrated in Fig. 21.

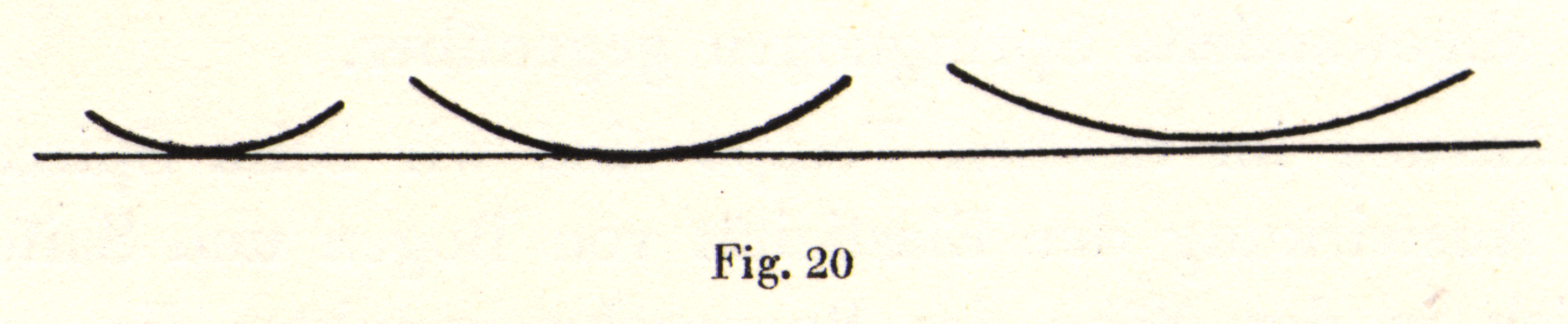

Depending on whether contact with the string takes a shorter or longer time, the tone can sound pointillistic, or it can sound broader (Fig. 20).

With prolonged contact duration, it can almost turn into détaché.

The tone quality depends not only on the choice of sounding point, but on the evenness and correct height of the bow’s bounce. The evenness of the bow’s action is ensured by an unhindered sequence of movements, taking care to stay relaxed. By applying minimal force, we can regulate the direction of the bow and the degree of tilting, and determine the speed. The height of the bounce should not be enough to make unpleasant extraneous noises in the tone quality.

By balancing the various objective and subjective playing measures involved in tone production (choice of sounding point, bow pressure, bow tilt, hand and finger activity), one can project tone in every dynamic nuance despite the brevity of the individual off-the-string notes.

Let us now take a closer look at the bow hand, because its mobility is the main condition for the success of this bowstroke. It makes swinging motions in the same number of oscillations as the bow performs strikes the string. Fig. 21 shows the combination of vertical (striking) and horizontal (lateral) movements—the direction of movement is therefore almost diagonal.[2] The wrist and fingers work together in a coordinated pattern: when the wrist moves one way, the fingers adjust at their base knuckles; when the wrist moves the other way, the fingers straighten at the base knuckles but bend at their middle joints.

The thumb participates in the swinging motion of the hand without significantly changing its position relative to the metacarpal. However, its point of contact with the bow changes in a way that requires careful study. Understanding the mechanical necessity greatly facilitates execution.[3]

Before the bow strikes the string, the thumb is positioned more horizontally at the frog (see image 54 of the Appendix). When the bow lands on the string, the axis of the thumb is more vertical above the frog (see images 57 and 58).

Between these two thumb placements, there is a gently swinging movement that we can practice without the bow as an exercise. Hold your forearm horizontally in front of you with the back of your hand pointing up, then perform multiple flexing and extending motions with your hand. The rotation happens at the wrist around an axis that goes perpendicularly through the forearm and transverse across the hand. When you continue this swinging movement with the forearm at an angle to the upper arm (like normal playing position), you can feel how off-the-string strokes work—they are basically hand flexion and extension around the axis of the wrist joint.

If you do not learn the movements in this step-by-step way, it is hard to figure out off-the-string strokes. By doing this exercise, your arm automatically gets into the right position while your hand creates the diagonal bow movement you need. This exercise is not exactly the same as a real off-the-string stroke, but your body will automatically make the small adjustments needed when you actually play.

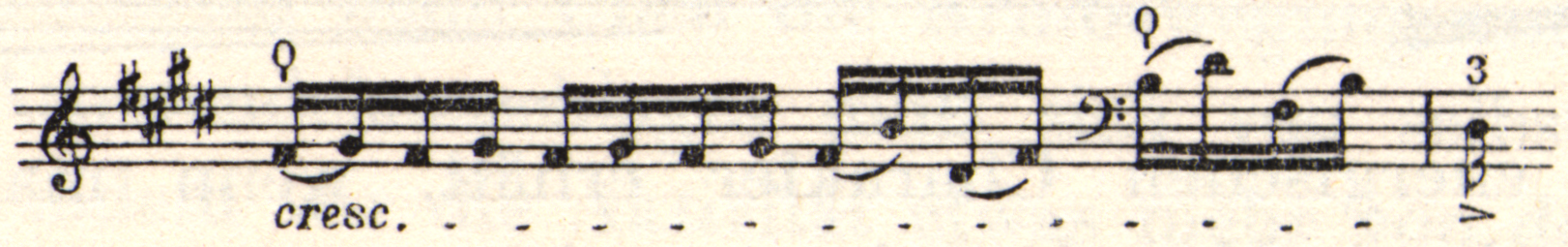

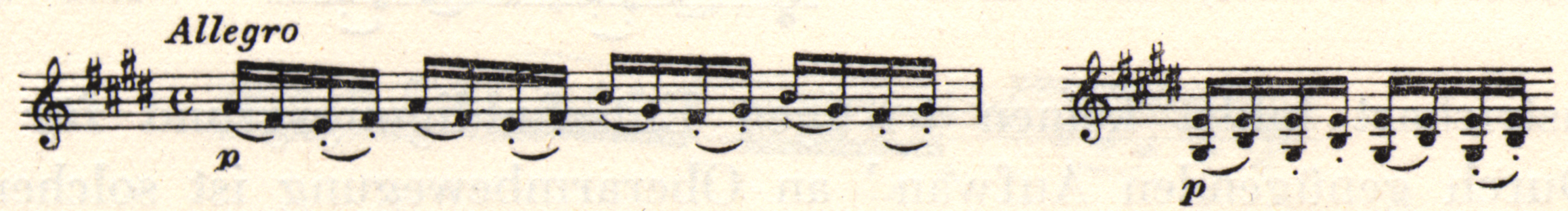

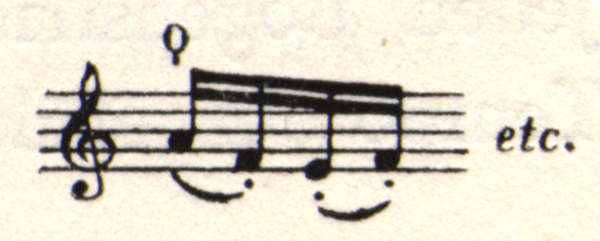

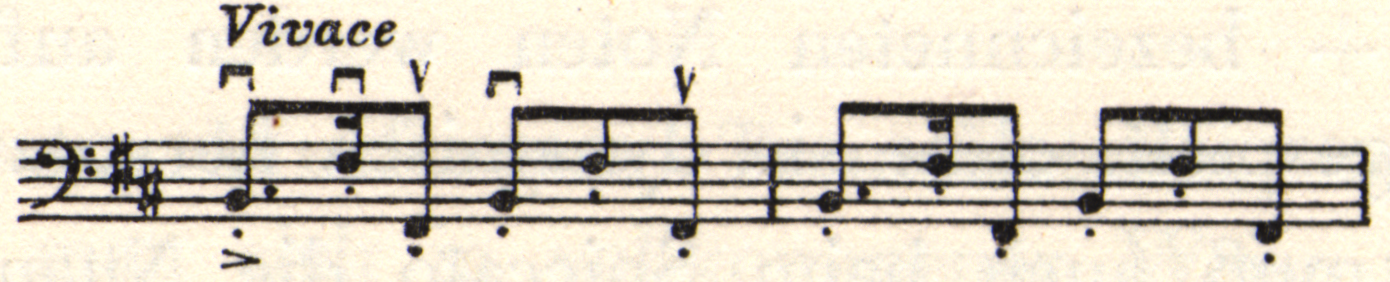

Now we must remember one more important fact. Let us play this passage:

in a very slow tempo, keeping a longer pause after each note, in one of these ways:

![]()

This execution is only possible if the arm participates in the action and the bow grip is somewhat firmer than usual. Your arm executes the movement, your elbow stays roughly horizontal, and your upper arm swings backward and rotates somewhat. (Slow off-the-string strokes are essentially “thrown” strokes!)

The best way to master rapid spiccato movements is to begin by practicing this slow movement methodically. First, practice the longitudinal rotation of the upper arm without the bow, positioning it as shown in image 55 of the Appendix. Then, keeping the height of the upper arm as unchanged as possible, gradually rotate the forearm and hand downward and back, as shown in image 59. (However, when we practice the basic movement slowly, it only contains a tiny hint of the complex arm rotation movement described above.) As we speed up the tempo, the arm makes smaller and smaller movements. The fingers and wrist increasingly take over the work, guiding the action of the bow. When we reach a certain speed, the arm appears to be almost motionless.

In reality, the arm is not motionless, but the larger arm movements we used in slow practice have compressed into much smaller ones—just what is necessary. We call this “movement condensation.” (Here is how it works from a physiological perspective: we the hand up and down in a vertical direction while holding the forearm loosely in a horizontal position. At faster speeds, we can feel the elbow moving slightly up and down as a counter-movement. Without this balance, the arm would soon stiffen and cramp up.)

We cannot consciously control these balancing movements—they happen automatically when the body makes active movements, affecting muscle groups above or below the main area of activity. The extent of the balancing movement depends on the quality of the main movement. The better your main technique, the less compensating movement you need. It is best not to worry about the latter at all, but to focus on correctly executing the main movement. (For example, if someone suddenly pushes you from behind, you automatically work to regain your balance—you don’t consciously think about making defensive movements.)

Famous pieces that use this fast spiccato technique include Popper’s Dance of the Elves, Davidoff’s At the Fountain, the scherzo movements from Mendelssohn’s Trio in D minor and Brahms’s in C minor, etc. Here, we are focusing on analyzing the technical methods that allow us to shape the music according to our musical ideas—we will save the aesthetic discussion of specific pieces for Part II of this book.

Once we have practiced enough to coordinate spiccato effortlessly on one string at any speed, we can move on to incorporating string crossings into the movement.

In the following measures from Mixed Fingering and Bowing Exercises (Schott, Mainz),[4] and all the variations derived from it, the string crossing is determined by active finger adjustment at an appropriately slow tempo. In the moment before the string crossing, the application of the double-lever movement brings the bow into the correct position for playing (i.e. at a right angle to the string, and if we wish to achieve the same volume, the same degree of tilt).

As we have already shown, the faster the tempo goes, the more the activity of the fingers decreases. The momentum the arm imparts to the bow is simultaneously used to change bow direction. The fingers should respond reactively, with all joints as loose as possible to allow the bow free movement. An active finger movement would inevitably ruin the rhythmic precision of the spiccato, and make the arm stiffen. Plus, beyond a certain speed, it becomes impossible for the fingers to keep up anyway.

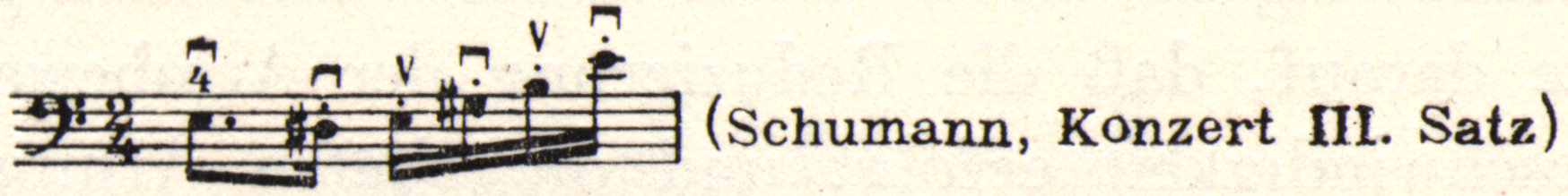

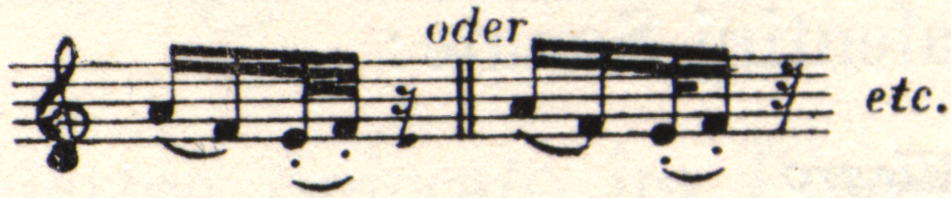

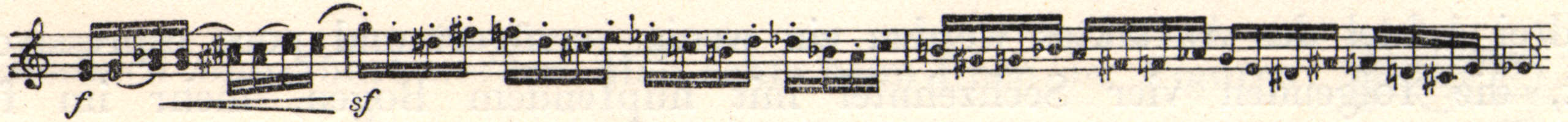

The main difficulty in Davidoff’s At the Fountain, for those not properly trained in bow technique, is the string crossings, especially in those places where we must play three sixteenth notes on one string and one sixteenth on the other, as in this example:

Here, the over-eager virtuoso cheats by playing like this instead—whether consciously or unconsciously!!

![]()

The proper technique requires the hand and fingers to be independent from the arm, which can only be achieved through loosening and deep relaxation of the arm muscles.

The difficulty of this passage, from a technical perspective, is the need to switch instantly from one playing plane (i.e. the A-string) to another (the D-string). This passage alone proves that it is absolutely necessary to limit certain functions to just the hand and fingers without involving the arm.

Regarding the agility of the fingers—which we claim for cello technique, unlike playing styles of past eras—let me emphasize again that all possible finger movements (except for accents made by sudden finger movements) must be smoothly connected through the movement of the arm. While double-lever action, as well as flexion and extension, lateral rotation, wrist flexion and extension, and rotation of the wrist can be performed by themselves as independent movements, ultimately they are just extensions of movement that originates from the upper arm.

The more vigorous the arm’s propulsion, the more the active role of the fingers changes into a reactive one. Arm momentum and increased finger activity, on the other hand, contradict each other. The slower and more deliberate the movement, the more active the fingers need to be for string and bow changes (see No. 5 of the editor’s “Special Studies”).[5]

So we see again and again that looseness as a fundamental law of bow holding and arm guidance runs like a red thread through the entire system. This principle is so universal that whenever we hear stiff, unbalanced playing, we can conclude there’s stiffness in the arm (whether in the shoulder, upper arm, or forearm) and particularly a lack of mobility in the fingers; conversely, wherever we see a lack of momentum in the movement, we can certainly expect a deficient technique and uncontrolled, unidiomatic playing.

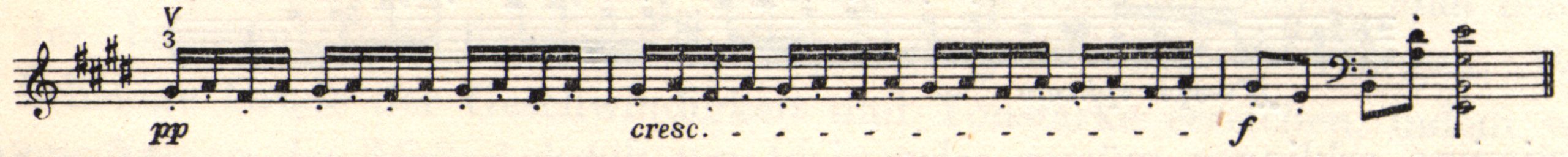

Spiccato requires surprisingly little force—we are not even moving the full weight of the bow (about 80g), since the natural elasticity between the bow. The hand only needs to guide the direction of the movement. Play the following exercise, using minimal arm movement:[6]

We cannot establish specific rules about how much force to use for different situations; our muscular sense is the most reliable indicator for applying just the right amount of force. True motor dexterity shows its triumph when we can effortlessly master notoriously difficult passages and make them sound easy!

Physiological analysis of movement also readily explains why spiccato so often causes fatigue, overexertion, and even pain in the arms, especially the shoulder. Acoustically, this problem manifests itself in indistinct-sounding individual spiccato notes, which transform into something that sounds more like détaché. We hear this quite often with students in longer spiccato pieces like Popper’s Dance of the Elves, and sometimes even with professional players. Of course, this change in bowstroke changes the whole character of the piece! Premature fatigue comes from inappropriate tension in the upper arm. The reason often lies in forcing the speed. Increasing tempo through strenuous effort always distorts technique and at best, is only successful by accident. However, if a student has a strong will to build technique by developing good, intentional movement, they will easily be able to increase the tempo as desired after sufficient practice.

If you notice arm stiffening, don’t keep practicing right away. First, completely relax the arm. By consistently training yourself to relax, you gradually increase the amount of time you can play, and your playing speed can automatically increase. This is a good guideline for practice: when a motion becomes stiff, the speed must be too fast. It stands to reason that the exaggeratedly fast spiccato we often hear does not come from artistic considerations, but from a state of compulsion! The sound effect is comparable to a convulsive tremor of the left hand.

In Dance of the Elves, for example, the real challenge is not the “shaking” motion (which requires minimal effort), but that the shoulder has to keep the upper arm suspended evenly for a very long time, especially when playing on the A-string. We can counter this fatigue by slightly lowering the upper arm as soon as we feel tired, without disrupting the off-the-string movement. For someone who has to hold their arm horizontally, it is already a relief to be able to lower it by ten degrees, or move it back and forth at a 20-degree angle. It is not so much the movement itself that is tiring as staying in a state associated with tension. This upper arm adjustment (which we use to relieve strain, and which should only be used when absolutely necessary) must stay coordinated with the “swinging movement” of the other parts of the arm. That is, it must occur synchronously.

For fast spiccato, the bow position is determined by its elasticity and center of gravity. But with slow off-the-string strokes (or the ricochet stroke), we have some options in determining the position. For moderately fast spiccato (as in the etude mentioned earlier at ♩ = 80), we ensure that the hand and fingers keep oscillating reactively in the diagonal direction of the stroke’s movement. This causes the bow to come off the string in short strokes. The speed of the spiccato depends here on the tension-free mobility of the lower parts of the arm and the impulse of the oscillation. (A quick note about relative tempos in different performance venues: the intelligent, experienced artist will choose a slightly more moderate tempo in a large hall than in a small one.)

In fast spiccato, which must be executed more in the upper half of the bow above the balance point, the involvement of the arm in the movement is almost zero (a “stationary arm”). But it would be wrong to conclude from this that we should restrict arm movement from the outset when practicing. The reduction in the “pendulum swing” of the arm should happen automatically as speed increases, as we allow the activity to come from the hand while the upper parts of the arm perform small secondary compensating movements. The strength of tone depends on the precise way the bow drops onto the string (i.e. the height of the fall) and the degree of bow tilting. When the tempo is more moderate, we need to make larger arm movements and exert more energy. This slower, more active type of off-the-string bowing is also called ricochet.[7] We can easily achieve any desired degree of speed and volume by regulating the amount of hand and finger activity required for the bow to drop onto the string with the arm’s momentum. Here, in contrast to fast spiccato, the bow doesn’t come off the string automatically from its elasticity—instead, we utilize its elastic rebound combined with generous arm movements.

So, the following rule applies to practicing spiccato: start at a slow tempo with generous arm movement. Let the bow fall onto the string near the balance point. Consistently use the same part of the bow, using active wrist and finger movement like that we would use for the “grip change” technique when crossing from one string to an adjacent one. Also, use finger flexion and extension.

Practice each of the spiccato exercises in the present author’s Mixed Fingering and Bowing Exercises, as well as the aforementioned etude, in this way. (There is also a very instructive study in off-the-string bowing in Servais’s Caprices.[8]) Then, reducing the arm movement, we can move to a faster sequence of notes in which the hand and fingers behave more passively and the arm’s impulses are transmitted to the bow through reactive, oblique wrist movements (quasi as a continuation of the forearm).

At even faster tempos, use slightly more hand activity, but restrict the arm movement even further (the so-called “stationary arm”). Remember this rule: the slower the tempo, the greater the swing of the arm.

We can combine spiccato bowing with détaché and martelé techniques to create many different tone qualities. The sounding point and bow pressure also affect the tone color. Just as a painter mixes colors to create different shades, we can use these factors to create a whole range of tone colors while keeping the basic character of the off-the-string stroke.

A martellato-spiccato works well for this passage from Dvořák’s Cello Concerto (page 3, third-to-last system[9]):

This creates an exceptionally energetic character when played in the middle or lower third of the bow with martelé-spiccato. Accent the first note of each sixteenth-note group in measures 2, 4, and 5.

Use the same approach for the opening measures of Dance of the Elves.

These measures must sound fortissimo—and we can’t achieve this effectively with passive or reactive oscillation movements. Use a very active hand and play in the lower third of the bow using all the hair. The first three measures should sound like a fanfare that calls the dancing elves into action. (See the remarks on Dance of the Elves in the second part of this book.)

The next two measures transition from fortissimo into a delicate piano. The type of movement changes from the active, controlled type into a loosely “swinging” spiccato approach.

During the next measure and a half, the player has time to gradually move the bow to the correct stroke position. Meanwhile, hand activity decreases and the arm starts to provide the necessary impulses. The area beyond the balance point (toward the tip) is where to play more delicate spiccato strokes.

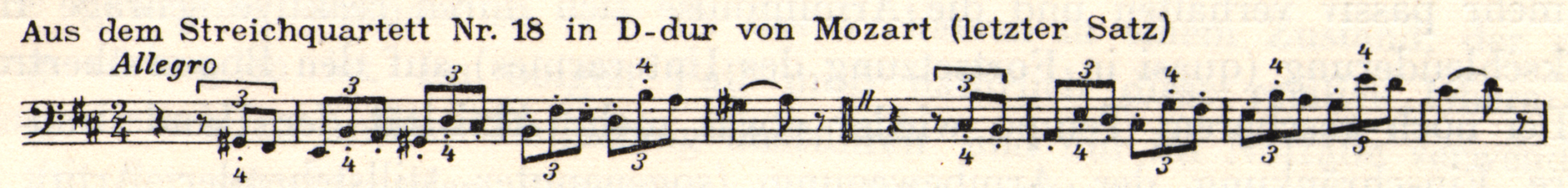

When difficult string crossings occur during a spiccato passage, you must return to the balance point area, as shown in this passage from the final movement of Mozart’s String Quartet No. 18 in D major:

Certain regions of the cello do not work well for pure spiccato bowing: the lower registers of the C- and G-strings, and the very high positions of the D- and A-strings. To avoid poor sound quality, cellists should change from spiccato to a kind of détaché-spiccato in these areas—for example, in Dance of the Elves during passages marked forte and those that are up in the “rosin region.”

This détaché-spiccato works especially well when crossing three strings, as in Popper’s Dance of the Elves (page 1, system 6, and page 2, last system) and the Valentini Sonata, second movement, second-to-last system.[10] For the sake of tone quality, we may modify the bowing without hesitation. However, the musical idea must always be taken into account when making arbitrary changes to the bowing. Above all, one must be careful to ensure imperceptible transitions and timely preparation of the bow arm and the left hand.

In this passage from the Valentini Sonata (page 2, fourth-to-last system), the left hand must adjust in preparation for the next figure to be played. Even a delay of a fraction of a second is enough to cause the bow to get stuck:

This example from the Valentini Sonata (first movement, last two systems) shows a transition from slow, soft spiccato to a fast martellato spiccato (or détaché-spiccato) in forte:

As the volume and tempo change, the bow moves toward the normal contact point.

Sometimes you can replace spiccato with quick ricochet strokes over a few notes while keeping the same sound character. In this example from the Valentini Sonata (last movement), ricochet creates a cheerful, exuberant character. Use spiccato only for continuous passages of equal notes. Individual notes, especially when they are metrically differentiated, can only be reproduced with a spiccato sound through the use of ricochet, for example in the last movement of the Valentini Sonata:

And also in the the Strauss Sonata, third movement, first theme:

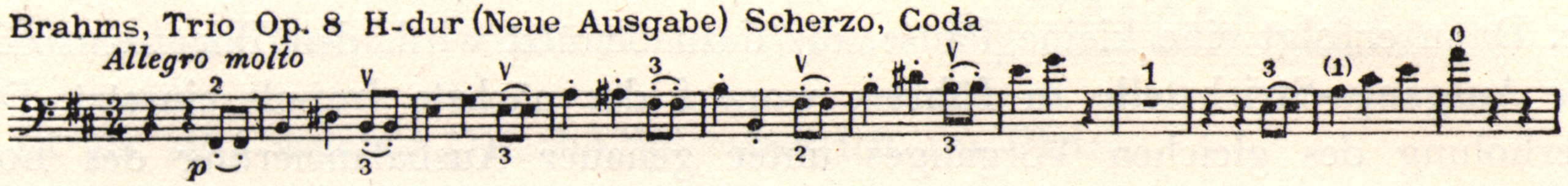

And in this striking passage from Brahms’s Trio in B major, Op. 8 (revised edition), in the coda to the scherzo movement—light, soft, fast, rhythmic:

and the Schumann Concerto, last movement:

These modified spiccato types are hard to execute at the tip of the bow. Another variation on the ricochet is an off-the-string stroke that combines several notes on one bow direction. Here, too, one can distinguish active movements from freely rebounding ones.

We use the former when there is an alternation between two slurred and two separated notes, or when, as in the second variation in Servais’ Fantasy on Schubert’s Sehnsuchtwalzer,[11], two off-the-string notes follow each bowstroke (tremolo stroke). Performed at a rapid tempo, this represents:

The tremolo stroke[12]

This is a freely rebounding movement. Examples from the Valentini Sonata:

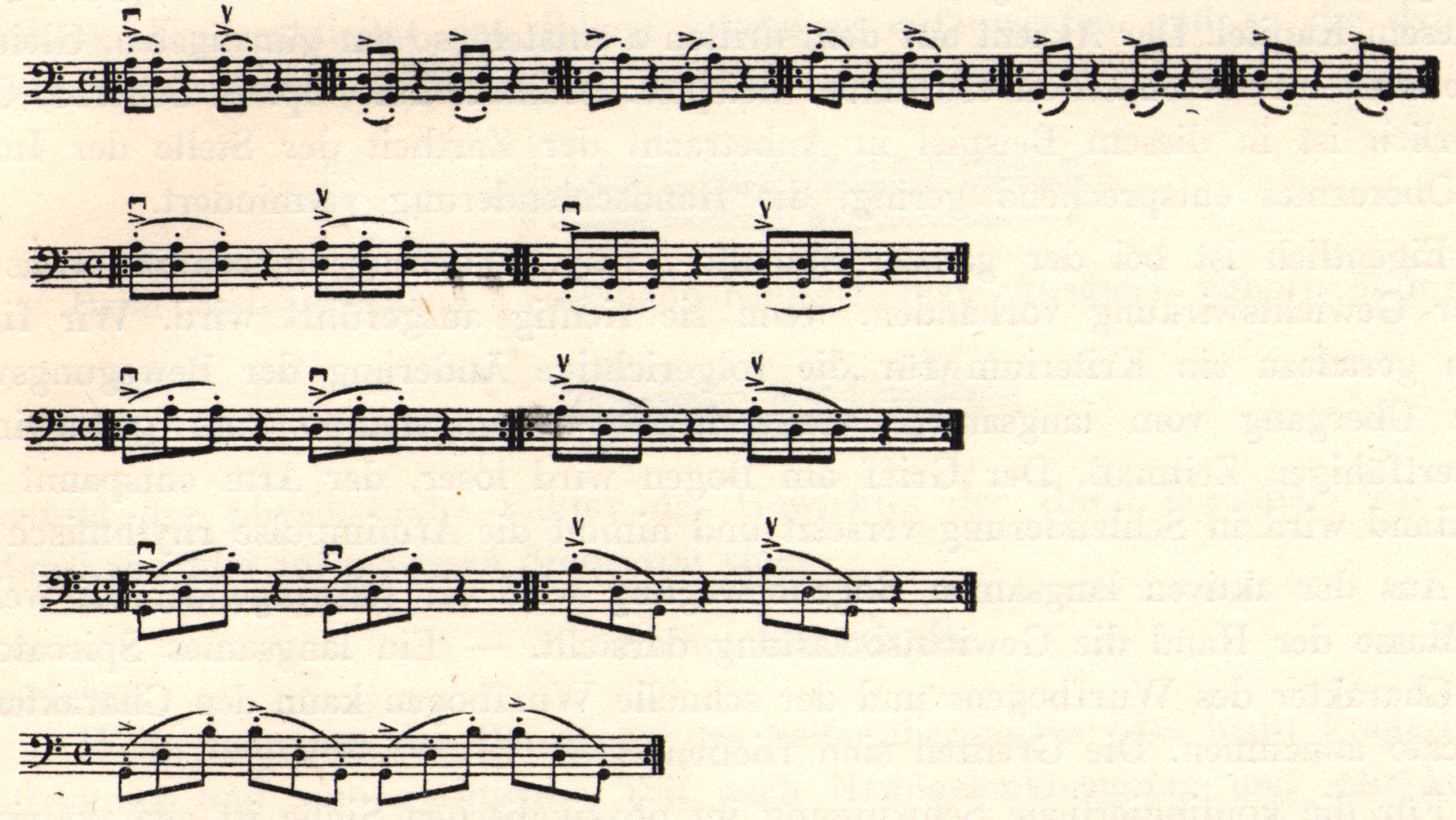

The following exercises explain how to learn the tremolo stroke. It can be executed on one string, on two strings, and over two strings in alternation.

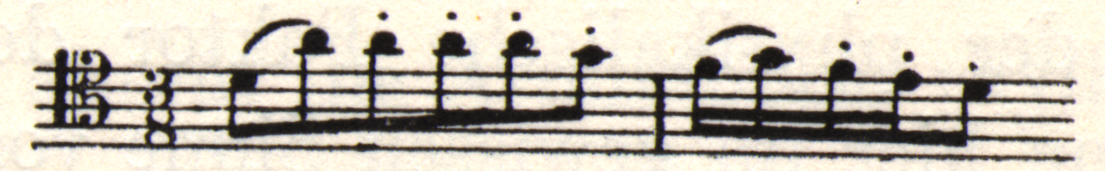

First, practice this exercise:

We will analyze it in a slower pace: at a moderate tempo, we naturally perform all movements with greater arm movements and active, flexible hand and fingers. Make sure to pull the bow straight, moderately tilted.

The “impulse” of the movement happens on the first note; with the second, the hand movement is reactive. Both notes must be articulated briefly, without rhythmic displacement. The arm makes a calm movement, as in legato bowing.

The main accent, which should be especially strong to enable rhythmically controlled execution even at the fastest tempo, lies on the third note, i.e. the strong part of the beat. Therefore, the bow must fall forcefully onto the A-string with an upwardly-swinging hand (and a grip change!). (See image 60 of the Appendix.) At the same time, however, the arm should be simultaneously pulled back and relaxed, so that the note on the D-string, on the strong part of the beat, falls into the final phase of the movement. The first two notes fall in the first phase of the grip change, the last two into the second phase. Then there is a short pause, which is used to return the bow-arm to the starting point so that the next impulse can begin. By repeating the same process and carefully balancing the weight of the bow at the balance point, the tempo can then gradually be increased. Here, the “swing” of the arm decreases slightly, and the metacarpal becomes more active. Make sure that the reduction in arm movement corresponds with the increase in tempo, and that the upper parts of the arm remain free from excessive tension. It should go without saying that a relaxed bow grip is an essential prerequisite.

For tremolo strokes on one string, the procedure is the same, except that more arm movement is generally needed. This is especially the case at faster tempos, where the movement requires a great deal of “arm swing”!

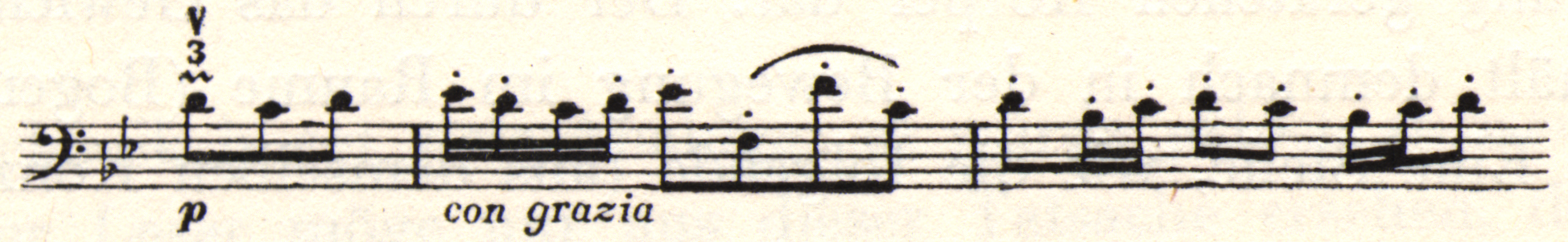

The previously cited passages from the Valentini Sonata can also be executed very well using the tremolo stroke. When practicing this figure:

make sure not to disrupt the rhythmic pulse, since this is tempting due to the dynamically weakened up-bow stroke. Don’t play it in either of these ways:

The difficulty of a bowstroke is no excuse for rhythmic mistakes! These can easily be prevented through sufficient movement of the upper arm.

These bowing techniques—such as spiccato, ricochet, the tremolo stroke, martellato spiccato, and détaché-spiccato—can only be mastered perfectly if we (1) perform the movement very slowly at first, (2) make ample use of the arm to create the right momentum, and (3) combine it with the motoric skills of the fingers. Then we gradually introduce shorter impulses from the arm and shoulder, and at the same time reduce the activity of the hand!

Finally (at a very rapid pace), gradually transfer control of the movement back to the hand. It is fundamentally incorrect to transfer all bow movement to the wrist right from the start. This never leads to the desired result.

Note:

As previously mentioned,[13] just as one may alter the spiccato stroke to the détaché-spiccato style for reasons of sound, one may conversely transform the détaché into an off-the-string stroke, for example in Bach’s Suite No. 3, page 2, seventh system:

![]()

By letting the bow come slightly off the string, this passage becomes clearer-sounding. At the same time, one can imitate the character of the second manual,[14] similarly to the fourth system of the first page, by using a legato stroke in the piano dynamic.

Another example, from the Gigue of the Eccles Sonata:[15]

A very soft détaché-spiccato bow is appropriate here.

An example of the transformation of a détaché or martelé into something similar to an off-the-string stroke can be found in the last four eighth notes of this excerpt from the Courante of the Eccles Sonata:

The next excerpt has a mixture of spiccato and ricochet:

The three eighth notes of the upbeat are played slightly delayed and poco espressivo. The four sixteenth notes that follow are played off the string in more of a free spiccato style, and the fourth eighth notes after that are played using ricochet.

Even the individual notes (marked with a +) that occur between the legato slurs can have the character of a spiccato or ricochet—for example, in the Allemande of Bach’s Third Suite.

The notes marked “+” are played like upbeats: short and light (using the spiccato-détaché), without dynamic emphasis.

When playing spiccato, one must also know how to utilize the nuances of dynamics and agogics (see Part II of this book, which discusses the art of performance).

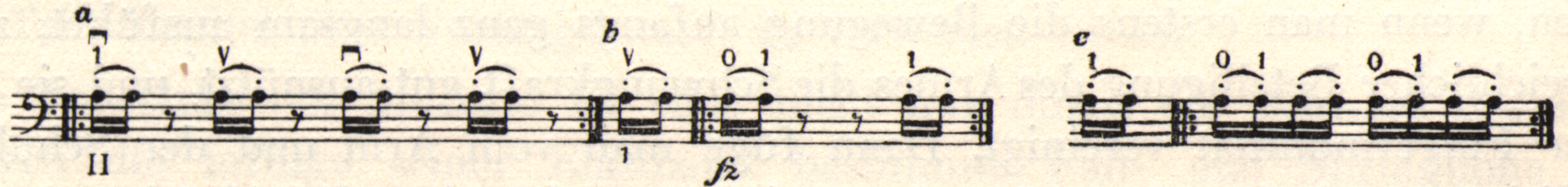

The intensity of the spiccato is not only determined by the weight of the bow and the height of its fall and elasticity-induced bounce; by generally relaxing the arm, one can add some of the hand’s weight to that of the bow, gradually making it heavier. To some extent, a touch of increased finger activity helps to get the bow bouncing more intensely, achieving a dynamic increase. It is therefore possible to play the following:

In the string crossings (e.g. in Schott’s new edition of the Volkmann Concerto):[16]

the physical factor of the weight of the hand becomes particularly apparent. In a certain sense, one can speak of:

The use of weight

If the movement involved in string crossings (i.e. finger flexion-extension and, to a lesser extent, wrist flexion and extension) is combined with the shoulder movement that enables the bowstroke, in such a way that the arm imparts an impulse that reactively drives the hand forward, the weight of the hand has a particular effect on the bow stick.

The mass of the hand effectively adds to that of the bow; together, they form a body set into motion. The bow, weighted by the hand, thus gains increased stability during its movement in space (i.e. in the rotation plane of the bow). We can see this in a passage like the following (from the same concerto) can, for example, be played precisely and taken at any speed. The prerequisite for the “gravity technique” is great relaxation in the upper arm and forearm, as well as the elimination of any inhibition in the shoulder and wrist.

Mechanics provides us with a good analogy: the heavier a car is built, for example, the lower its center of gravity; therefore, it can more safely negotiate a curve at a given speed. Similarly, the heavier a hand, the better it is for the string crossing in the above example. A light, delicate hand is generally at a disadvantage in bowing technique. It has to compensate greatly through active finger movements, whereas a more substantial hand can advantageously increase the swinging mass of the bow through “reactive spinning” while largely relaxing the rest of the arm.

This moment of coordinated combination[18] of multiple gravitational forces through reactive hand movement is also the case for the tremolo stroke (discussed in an earlier section of this chapter). The accent on the third A is created in the most favorable way.

The same applies to the example mentioned before from Brahms’s Trio, Op. 8, in the coda of the scherzo movement. Naturally, given the delicacy of the passage, the impulse of the upper arm is correspondingly small, and the hand movement is reduced.

Actually, achieving a precise spiccato or ricochet in the correct manner involves some use of weight. It is a criterion for the proper execution of movement, as well as for the transition from a slow, preparatory practice tempo to a faster “performance” tempo. The bow grip becomes looser, the arm relaxes, the hand is set into a spinning motion, the arm’s impulses ensure rhythmic unity.

The active, slow bow movement becomes the “swinging” one, in which the mass of the hand and the weight stabilization become decisive factors in the characters of the spiccato and ricochet. A slow spiccato can have the character of a ricochet, and a fast ricochet can take on the character of a spiccato. The boundaries are fluid.

Continuous oscillation, in the physical sense, is characterized by the periodic repetition of the impulse, and and the elastic connection between the actively moving body part and the passively moved body part (in this case, the wrist). Physiologically, we must avoid needless twisting; in practical terms, this means avoiding unnecessary tension!

We can find many analogies to this in mechanics; describing them all is beyond the scope of this text. The reader need only realize that good technique is subject to the laws of nature, and that the optimal acquisition of comprehensive bow technique depends on the adjustment and adaptation of our natural playing apparatus.

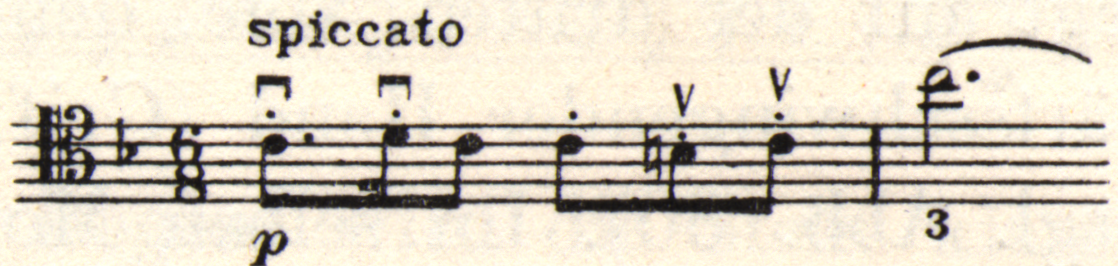

Hints for learning off-the-string arpeggiated bowing

As we previously mentioned, it is not possible to make a clear distinction between the elements of spiccato and ricochet bowing, even taking into account the mechanics of producing sound. For example, off-the-string arpeggiated bowing, when done slowly, is a ricochet stroke, just like the slow spiccato. In a fast tempo, on the other hand, both it and the tremolo stroke become freely-oscillating bowstrokes with the character of a spiccato.

When done well, off-the-string arpeggiated bowing has great charm. We can find it, among other places, in the first movement of the Dvořák Concerto. (See also the present author’s Waldschrat-Suite, published by Simrock.)[19]

We would like to offer some tips for learning off-the-string arpeggiated bowing, starting with the tremolo stroke. The following exercises should be practiced one after the other at a slow tempo, with accurate rhythm, observing the rests; then, accelerando, so that the rests completely disappear and a continuous off-the-string arpeggio stroke emerges.

The different phases of the off-the-string arpeggiated bowing over four strings are illustrated in images 61, 62, 63 and 64 of the Appendix, which show the process as viewed from the front. (Images 65 and 66 show the hand from the side, demonstrating what the thumb should be doing during this stroke.)

Finally, practicing drum-like rhythms is recommended as another means for quickly acquiring good off-the-string bow technique. The following examples can be endlessly varied as desired:

- David Popper, Elfentanz, op. 39; Carl Davidoff, Am Springbrunnen from 4 Stücke, Op. 20. ↵

- Becker's note: "See Fig. 21." ↵

- Fig. 21: text: Abstrich = down-bow stroke, Diagonale Handbewegung = diagonal hand movement, Niederfall = downwards stroke, Strich = stroke. ↵

- Becker refers to his own publication, Gemischte Finger- und Bogen-Übungen nebst neuen Tonleiter-Studien für Violoncell, published by Schott in 1902. ↵

- Becker's 6 Spezial-Etüden zur Förderung gröszerer Leichtigkeit im Bewegungssystem des Violoncellisten, Op. 13 (Wilhelm Hansen, ca. 1921). ↵

- This exercise comes from page 21 of Becker's Finger- und Bogen-Übungen (Schott, 1913). ↵

- Becker uses the term Wurfbogen, literally "thrown bow," which is usually translated into English as "ricochet." ↵

- Adrien-François Servais, 6 Caprices, Op. 11 (Schott, 1852). Becker published an undated edition of these etudes, also for Schott, in the early 1900s. ↵

- Becker refers to the 1896 Simrock edition of the Dvořák Concerto. The excerpt shows measures 110 through 114 from the first movement. ↵

- i.e. Piatti's edition of Giuseppe Valentini's Allettamento, Op.8 No.10 (published by Schott as "Sonata X" in 1895), II. Allegro, measures 17 through 20. ↵

- Adrien-François Servais, Le Désir: Fantaisie et Variations brillantes, Op. 4. Becker made an undated edition of this work for Schott which claims to be "revised from the original manuscripts." ↵

- Becker uses the word "tremolo" in a different sense from the usual definition, i.e. a note that is reiterated very quickly with very little bow and separate strokes. Becker's usage indicates ricochet strokes under two-note slur markings. ↵

- Becker's note: "See this chapter, page 86." He refers to the passage concerning the use of détaché-spiccato in Popper's Dance of the Elves and the Valentini Sonata. ↵

- i.e. the second manual of a harpsichord. Becker's interest in historical performance (in which he was ahead of his time) means that he was likely familiar with the tone colors of Baroque instruments, and had them in mind for his interpretation of Bach. ↵

- Henry Eccles's violin sonata of ca. 1720, transcribed for cello. ↵

- Robert Volkmann (1815-1883), Cello Concerto Op. 33. Becker published an arrangement of this work for Schott in 1904, adding a cadenza. ↵

- Becker uses the word Schleuderung, which can be variously defined as "slinging," "spinning," or even "centrifuge." Becker's usage seems to describe the rotational momentum of the bowstroke. ↵

- Becker uses the word Summierung, literally meaning "summation." In this context, the Summierung concept suggests that effective bowing does not rely on just one isolated movement, but rather the coordinated combination of multiple physical forces: the weight of the arm, the hand's motion, and the bow's momentum all working together. ↵

- Becker's multi-movement composition for solo cello, Fantastische Suite aus dem Leben des Waldschrat (Fantasy Suite "From the Life of a Forest Goblin") Op. 14, published by Simrock in 1919. This virtuoso piece shows influence from both the Dvořák Concerto and Popper's Dance of the Elves, two compositions Becker mentions repeatedly in this chapter. The first movement, "Waldraunen" (Forest Whispers) features the kind of arpeggiated off-the-string strokes Becker describes here. Long passagework sections require the player repeatedly to cross three and sometimes four strings under one slur marking. ↵