On Agogics and Affect

“Agogics” is a term introduced into musicology by Hugo Riemann. In an essay on agogics from 1889, Riemann explained that certain performance markings arose from the fact that the expressive intentions of musical eras brought about the need for particular performance directions. “The eighteenth century saw the invention of crescendo and decrescendo (including the “Mannheim crescendo” of Canabisch, 1775[1]). The nineteenth century saw the invention of stringendo and parlando (for example, among composers in Meiningen under Bülow, 1880). Surely these performance directions were in use before, but not in the particular way that these more sensitive masters used in their quest for more passionate expression.”

The period about which Riemann wrote these lines saw a greater attention to musical detail. Expression on a grand scale was no longer sufficient; perfection was also sought in the smallest details. This tendency created the theory of dynamics and agogics. Its prerequisite is the theory of motivic structure and the art of phrasing.

Riemann defines agogics as a principle of good, correct performance, in which time signature, motivic structure, and harmony are clarified. It is only through the skillful use of agogics that we can bring real life, color, warmth and integrity to our performance. We can certainly agree with his view that poor use of agogics distorts musical expression and can turn something noble into something banal.

Besides dynamic shading (i.e. gradations of volume), an equally important factor is the idea of agogic nuancing, i.e. a fluctuation of tempo.

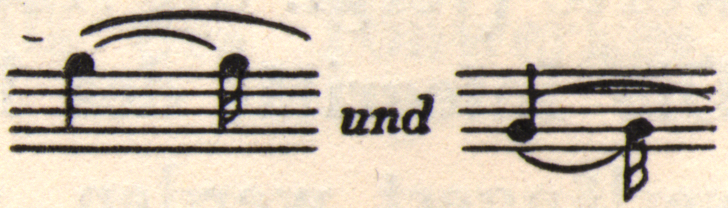

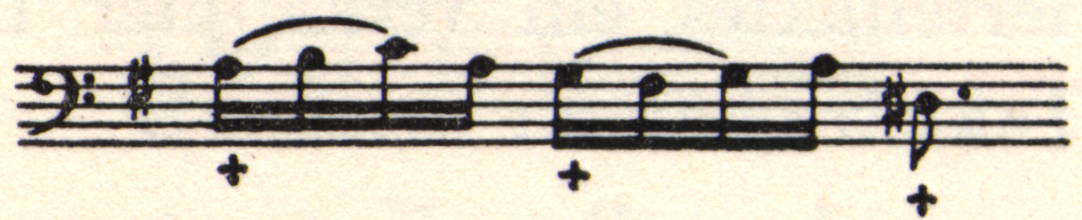

To explain this quickly, we cite an example that Riemann himself gives. The beginning of the prestissimo of Bach’s Toccata in D minor reads:

A distortion of this passage would look like this:

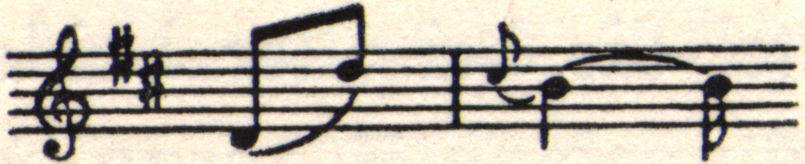

Since dynamic shading is absent from the manuscripts in the old organ works, a meaningful interpretation is only possible through slight lenghening of the tones that are the focal points of the motive. We can do this through minimal acceleration of the upbeats, and gradual disappearance of the unaccented endings, like this:[2]

If the demands of performing a work could be exhausted by observing all the performance markings indicated by the composer, the correct tempo, the dynamic and rhythmic demands, as well as the tone quality, then no further effort would be required.

Why then, in addition to strict adherence to time, should there be such a slight shift in tempo, in terms of minimal displacements to the beat? Is it just human nature to rebel against a prolonged, sustained sense of exact pulse? If it were just a human imperfection, however, it would not be justifiable to describe it as an artistic activity. It is hard to understand why we should not compensate for imperfections in rhythmic perception just as we do for the uneven movements of fingers and arms that beginners make. Just as we train players to smooth out their physical inconsistencies, we should also work to combine all the individual musical moments into one properly shaped overall musical flow!

The reason lies deeper. We do not know whether the problem of musical aesthetics has ever been considered from this perspective. Our desire for the subtle timing variations that agogics provides seems to connect with a basic human need to bring all our natural characteristics together into immediate, unified expression. This same connection between expression and emotion has been thoroughly studied in other art forms, but is strangely neglected in music scholarship—we find few references to this point in modern writings (except for those by Kretzschmar).

Even in everyday conversation, careful observers notice that people never speak with completely neutral tone and rhythm. Pitch and volume fluctuations appear even in the most ordinary speech—and much more so when people are excited, trying to persuade, courting someone’s favor, pleading, or expressing resistance. In short, whenever they speak with real feeling. Detailed phonetic studies have shown that even in the most beautiful oratory, every single syllable shows such fluctuations in pitch and volume. In sensitive, artistic people—those whose inner lives are more easily stirred than in emotionally sluggish and inexpressive individuals—everyday speech shows these same fluctuations. This suggests that every utterance carries at least some trace of emotion, however slight. For the psychologically trained observer, it’s easy to distinguish genuine expression from the false and artificial—to tell real feeling from affectation.

In theatrical arts, there’s a clear distinction between expression that comes from genuine depth versus surface-level sentimentality. The difference lies between authentic human content and mere beautiful appearance—between having or lacking an equivalent to true emotional expression. Words and gestures are subject to the same laws of effect when it comes to their impact. The deepest and most powerful effects occur when there’s a restraint that limits the scope of external movement to only what’s necessary (think of Eleonora Duse!).[3]

The differences in musical expression do not just involve obvious dynamics and tempo changes but also—usually in conjunction with subtle shadings of the accent—in the shifting of rhythmic elements within the metric unit, creating concentration and dispersion, rises and falls, tensions and releases.

But in musical language, everything beyond pure technical exercises is really built on emotional expression—and these need no special agogic treatment. The old theorists observed this very precisely, and the fact that pre-classical music is simpler in terms of harmonic and melodic structure doesn’t diminish the value of their practical insights into theory. Quantz wrote in his work On Playing the Flute about various musical affects. He compares a musical performance to that of a speaker, since both have the same goal: to touch the heart, to arouse or calm the passions, and to transport listeners now into this, now into that emotional state.

Every affect has a different tone color—a different dynamic.

Quantz says: “A good performance must, firstly, be: 1. pure and clear; 2. round and complete. Each note must be expressed in its true character (note fidelity!!) and in the correct tempo.” He recommends distinguishing between notes that fall on heavy beats versus light beats (downbeats versus upbeats!). “Light and flowing” (don’t let the difficulty show—no grimaces!); “4. be diverse; 5. expressive, and in accordance with every character that arises.” (There are both primary and secondary characters.) The following are decisive for determining emotional characters: the tempo marking of the piece, its key, the harmony, and dissonances! Quantz distinguishes between the joyful, the magnificent, the bold, and the flattering. The main ideas must be distinguished from the subordinate ones.

With the support of modern psychological research, we can grasp this concept of musical affect much more broadly today. By “affect” we don’t just mean the participation of a feeling, loving, or hating mind—or what we call a “state of conscious emotion” in practical life. We mean something broader: the vital force that stands behind all our expressions. This force takes the most varied forms, but it always appears in personal ways.

It reveals an integral part of our being, one that is associated with character. Individual personality traits are revealed in it, just as they are in facial expressions or handwriting. However, if it is to be a vehicle for personal expression in music, we must transcend its purely mechanical aspects, because the mechanical is the impersonal—it’s just the material that we use freely to create and shape expression.

This understanding also leads to an important warning: don’t let your technical struggles show through, and make sure you rise above purely mechanical playing. In technical practice, we experience something similar to this principle: for true artistry, we work toward making our tone pure and free—liberating the sound from the heaviness that comes from poor bowing technique or incorrect impulse control.

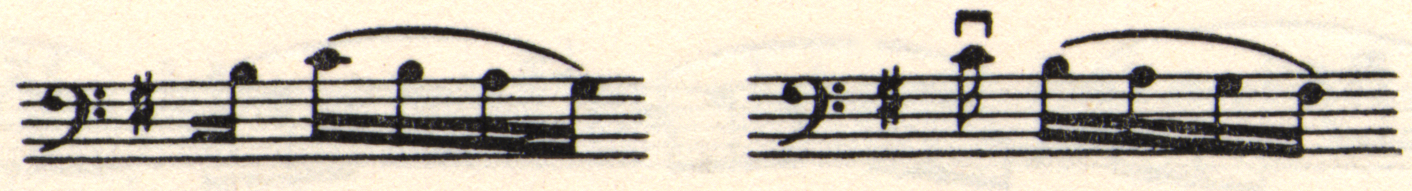

We derive the elements of agogics and affect from a common source of personal expression. We have learned that every living expression, be it in words or tones, brings with it a shift of rhythm within the metrical unit. Let us consider an example from the Schumann Concerto:

The yearning of the Romantic comes to life in this theme, especially on the high G, which is the climax of a tender, pleading emotion. A slight lingering is unavoidable here. To sound truly expressive, you need to take time!… But as we know, going from the sublime to the ridiculous is just one step away. How easily the emotion—tender, despite all its passion—could be coarsened into one of maudlin sentimentality through the overly intense use of expressive means. This would happen if the vibrato were not varied (i.e. by using more intense vibrato on the G-sharp, then more still on the climactic high G), or if the portamento from the high G down to the A were not accompanied by a diminuendo.

The following example, which comes from the present author’s Spezial-Etüden, is similar:

Let us examine the first measure of this etude, which should be played as a study in tender emotional expression, and see what techniques make this delicate feeling work! The success depends on ensuring that the three sixteenth notes that fall between these sustained notes are not played completely evenly.

They should not stand isolated on their own, but rather serve as connecting bridges between the emotion of the high F-sharp and the one an octave lower. Therefore, we should relate the sixteenth notes to the two “emotional anchor points” on either side of them, so that the expression stretches from the first quarter note to the third, but differently from the third quarter note to the first of the following measure.

In musical logic, we should therefore allow the D to participate in the emotional expression of the first F-sharp by stretching the note a little without any dynamic emphasis (agogics!), and playing the two following sixteenth notes somewhat more indifferently to compensate for the loss of tempo.

Perhaps many musicians’ resistance to the verbal interpretation of music stems from the fact that tension and release—the primary musical experience—should not be compromised by a comparison to extramusical things.

The artist speaks through the artwork more directly than any words could. Linking music to external stories or events is only justified when the composer has specified an existing program (such as those in compositions by Berlioz, Liszt, and Strauss) or a portrayal of nature (Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony). But even in non-programmatic compositions, there is still room for poetic interpretation. After all, the lyrical quality of music is so immediate!

Agogics are not just about making phrases clearer or more understandable. Yes, agogic differentiation is very helpful in clarifying musical structure, but beyond that it also creates scope for the modulation of emotions and allows for some flexibility in timing, dynamics, and expression within the overall movement.

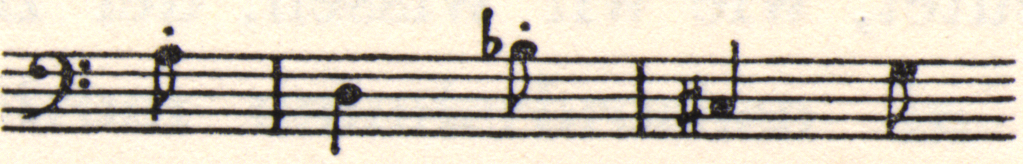

Let us look at a concrete example of this from the first movement of Haydn’s Concerto in D major:

The simplified motive would go like this:

The two octave notes (D to D) form an upbeat for the grace note on the downbeat, which should be stretched a little here at the “expense” of the notes that follow it, i.e. the weak phrase ending.

The sequence of scalar notes in the solo part should therefore accelerate gently (or as Riemann puts it, “rush towards the goal note”). We can do this through increasingly shortening the lengths of the notes (for further explanation, see the section on rubato).[4]

![]()

The integrity of the rhythm demands that the first few notes be lengthened so that the overall acceleration is logically justified—it is a process of catching up, of balancing! The constant balancing-out of longer and shorter note lengths constitutes the agogic shading. Together with dynamic gradations, it fulfills the demands of a higher performance art.

Often, several such shifts occur within a single melodic line. Here is an example from the first measure of the opening solo in the Haydn Concerto.

The shortening of the second and fourth notes following the agogic accent (the extension of the first and third sixteenth notes) is called Abzüge,[5] a term used by Emanuel Bach. Such Abzüge are characteristic of so-called “weak endings.” In longer sequences of equal note values, the agogic shading often enables the recognizability of the melodic progression.

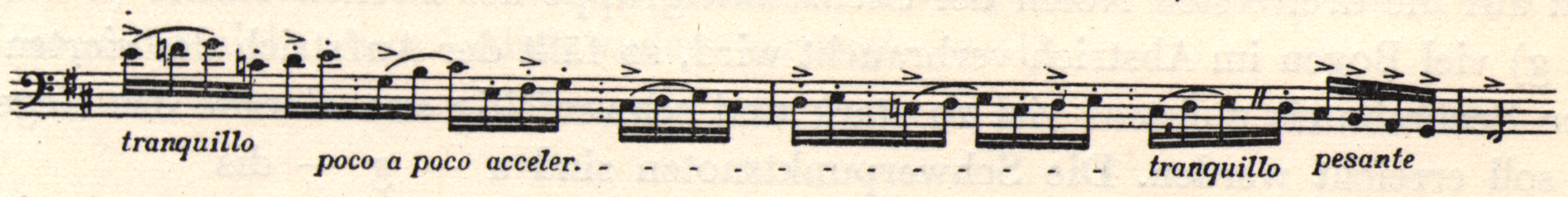

For example, in the development section of the first movement of the Schumann Concerto:

A further example from Brahms’s Double Concerto, first movement, rehearsal D:

Agogic accents play a special role when the beat emphasis is shifted within the time signature (Dvořák Concerto):

Here, within the 4/4 time signature, there is a disguised 3/8 time signature (as indicated by the dotted barlines).

The next passage, which comes from the same concerto, should be performed rubato (see also the essay “On Rubato” and my Dvořák analysis).

It also contains agogic accents in the last two measures: the B-flat should not have dynamic emphasis, but rather should stretch slightly while maintaining the same volume of tone; the B-natural is a harmonic intensification, because it is like a spiritual release. (Absolute adherence to note values would reduce this passage to insignificance.)

But agogic influence affects not only the details of musical works, but also the phrasing of entire movements. We can avoid the boredom that can easily arise in playing sequences if we increase the liveliness of expression (and not necessarily through a pronounced accelerando in combination with dynamics!).

We can effectively prepare for the entry of new thematic material by slightly delaying the preceding notes. An example of this can be found in the last measure before the beginning of the second theme in the first movement of the Dvořák Concerto.

Rushing through phrase endings without any musical reason for doing so is a mistake.

For more on agogic nuances, the reader should consult the performance analyses later in this section of the book. Agogics is essentially a small-scale world of temporal variations, similar to how rubato works, but on a larger scale.

Since the mere mention of performance instructions does not always help the student, this book is intended to meet practical needs too. Aesthetic moments run parallel with mechanical-technical issues, and with this in mind, we should draw attention to a few points:

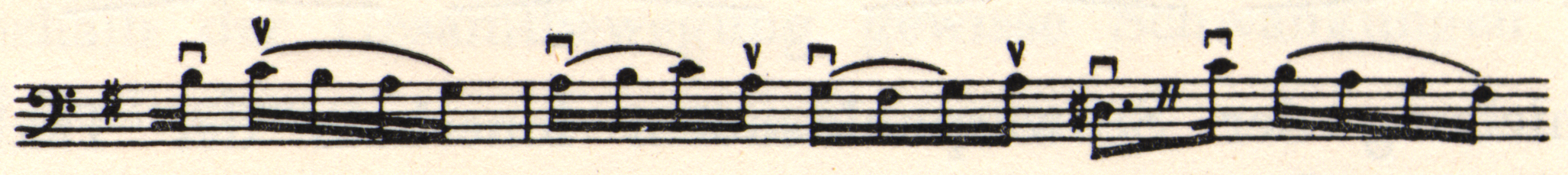

We have repeatedly emphasized the need to resist letting technique dictate musical interpretation. The following passage from Bach Suite I proves that the expediency of bowing sometimes conflicts with musical sense:

If we use a lot of bow in the down-bow stroke on the first three of the groups of four sixteenth notes in the second measure (A-B-C and then G-F♯-G), the up-bow stroke on the fourth and eighth sixteenth notes is usually much too strong and cumbersome. We should be aiming for quite the opposite. The “main notes” are A-G-D♯, as shown here:

The groups of notes that precede and follow them should be treated as their upbeats.

Only an awareness of musical necessity can help us choose the right mechanical measures here: saving bow on the down-bow and a gentle timbre on the up-bow. In the two places we have a single A on an up-bow, we can either play it from the string and make up the remaining distance in the air, or draw the bow through the air first before articulating the note further along the bow. It all depends on the motivic structure.

In the following example from the Dvořák Concerto, the first three sixteenth notes should be played with relatively little bow, as the energetic character requires being close to the frog. Don’t use too much bow! Play the fourth and eighth sixteenth notes of the measure immediately after the down-bow, but only briefly, because you should come off the string and “play through the air” to get back to the frog! Make sure to count the two dotted eighth notes on the third and fourth quarter of the bar correctly!

It seems paradoxical to claim that tempo fluctuations (agogics) are also possible on a single note. But first, the duration of each note must be measured relative to the other notes, and second, the staccato dot above the note requires it to be shortened. As long as the prescribed time signature is observed, the player is free to shorten the note as desired and play a rest during the remainder of the allotted time.

For an expressive performance of this passage from the Volkmann Concerto, the sixteenth note must be well separated from the preceding dotted eighth note, so that there is a pause of the approximate value of a thirty-second note.

In the following example, from the Gigue of Bach’s D minor Suite, the shortening of the upbeat note is best achieved through the marked use of the grip change technique, in which the bow only briefly and gently touches the string; for the remaining time of the notated note value, the bow is in the air (as a continuation of the grip change movement).

The agogic differentiation at this point should not disrupt the natural hierarchy of dynamics. That is, upbeats should be dynamically weaker than the following downbeat (unless the composer explicitly indicates otherwise, as in jazz).

- Christian Cannabich (1731-1798), the music director in the city of Mannheim, to whom the so-called Mannheim crescendo is attributed. ↵

- The German text in this musical example uses the words gedehnt (stretched) and Dehnung allmählich verschwindend (stretch gradually disappearing). ↵

- Becker refers to Eleonora Duse (1858-1924), a renowned Italian actress. ↵

- Becker's note: "See also the graphic representation for accelerando." ↵

- Becker's note: "Abzüge are therefore used for agogic accents under equal note values." ↵