On Appoggiaturas

The question of appoggiaturas[1] is a topic of much discussion, and to this day it has not been definitively resolved. Adolf Beyschlag’s[2] profound work, The Ornamentation of Music,[3] has provided extensive clarification on this complicated, multi-faceted subject.

To see the importance of the question, we should take note of this passage from page 103 of Beyschlag’s book:

“No other ornament has such a complicated theory as the appoggiatura; no other is a source of such continual confusion for anyone who studies older music. To bring some clarity to this perplexing matter, we are compelled to examine the development of the ornament in context. Above all, we must avoid unproven but nearly ineradicable assumptions about it. This includes, for example, that this is the symbol for a long appoggiatura:

![]()

and that this is the symbol for a short one:

![]()

It remains undecided which of the two errors has caused the greater confusion.

The reader will be aware that it was only shortly before the time of Bach and Handel that people began to notate appoggiaturas at all, instead of leaving them entirely to the discretion of the performer, as had previously been the case. Indications such as ‘hooks’ and ‘dashes’[4] served as symbols, which naturally excluded any indication of duration. But even when this small note symbol:

![]()

and subsequently this one:

![]()

were later introduced, such a tendency was completely alien, as these ornaments initially bore the character of short appoggiaturas.[5] J. C. Walther clarified this in 1732, writing that ‘the appoggiaturas (Accente) take a little off the value of the longer principal notes and half off the value of the shorter principal notes.’ Mattheson defined this in 1739: that single appoggiaturas take a little time from the principal note, while two-note appoggiaturas take half the value from it; thus making the first clear, albeit summary distinction between appoggiaturas into short and long examples. If we consider the somewhat vague hints at the meaning of longer appoggiaturas in works by Janowka (1701), Montéclair (1736), and Geminiani (1740), we exhaust everything that was known about the theory of this ornament up until the death of J. S. Bach in 1750, and the blindness of the elderly Handel.

Three years after the death of his august father, [Carl] Philipp Emanuel Bach published his groundbreaking Essay on the True Art of Playing the Clavier (1753), in which he presents a theory of Manieren (ornaments), worked out to the minutest detail, especially concerning appoggiaturas. Now, we might assume that the son had merely worked out and published his father’s teachings. There are, however, some major reasons to oppose this. Philipp Emanuel, whose father wanted him to be a jurist, had left the parental home in his twentieth year; he formed his own galant style among strangers, and from this emerged his theory of ornamentation. The galant genre could not do without the piquancy of freely-flowing, long-held suspensions, which the strict style would have abhorred. One thus circumvented the old prohibition by indicating unprepared dissonances with small appoggiaturas, but without neglecting to equip them everything that could recommend them to the ear. They received stronger accentuation and a duration that varied from half of the main note up to its full value. Philipp Emanuel’s textbook became the authority on the subject, and Marpurg,[6] for example, immediately modified his own system of ornamentation according to the new principles.

In his sophisticated theory, C. P. E. Bach naturally had to provide precise notation for the appoggiaturas he described. ‘For a long time (!) one has held these appoggiaturas to their true value, instead of indicating all appoggiaturas through eighth notes as one used to do. In previous times, appoggiaturas were of such different value that they were not systematized; with our present-day taste, however, we do less well without precise indication, the less all rules about their value are sufficient.’ Unfortunately, this reasonable advice found little attention among the best composers, with the single exception of W. A. Mozart; even with Haydn, Beethoven, Schumann, and Brahms, we find repeated relapses into the old notation, which indications short appoggiaturas with this symbol:[7]

![]()

The matter became even more confused when, around 1802, the old Italian-South German sixteenth-note mark still used by Gluck, Haydn, and Mozart, i.e.:

![]()

began to be proclaimed as the standard sign of the short appoggiatura. Even though composers up to the era of Berlioz and Mendelssohn took no notice of this innovation in notation, they could not stop some publishers from making use of it, which opened the door to general confusion.

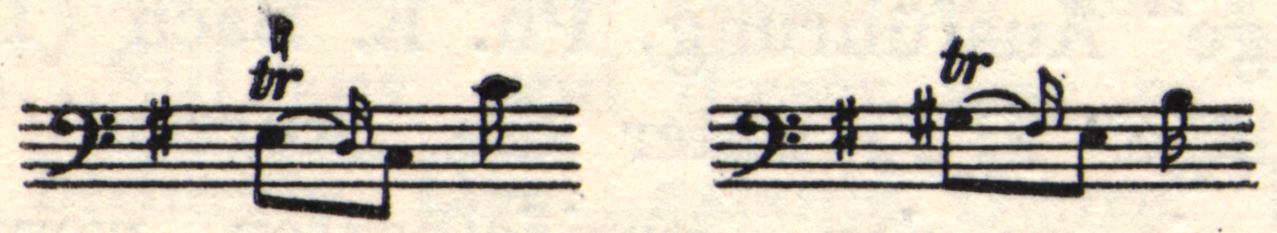

One more prejudice must be eliminated before we can gain some clarity about the question of appoggiaturas. The ‘serious musician’ would understandably fear for their artistic reputation if, in older music, they performed this notated phrase:

![]()

so that it sounded like this:

![]()

If we counter that such an interpretation is indeed correct for the Haydn-Mozart-Beethoven era, but not for the earlier era of Handel, Bach, Gluck, Scarlatti, Tartini, etc., we need to support this claim with verifiable evidence. Before J. A. Hiller[8] and Türk,[9] one will not find a single theorist who approves the above interpretation; on the contrary, everyone agrees in demanding the opposite.

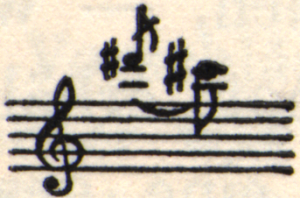

For example, for the following notation:

![]()

Quantz (1752) explicitly warns us not to play it like this:

![]()

In 1757, Agricola declares the following to be correct:

![]()

…and that this is incorrect:

![]()

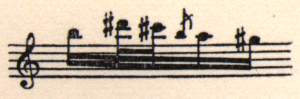

In 1753, C. P. E. Bach and his followers categorize the following as ‘short appoggiaturas’:

![]()

Only Hiller (1780) and Türk (1787) classify them as ‘uncertain, although at the present time they are usually played in the short way,’ thereby transitioning to more recent practice.

The following version is now generally adopted and remains absolutely binding for the works of Haydn, Mozart, Cherubini, Clementi, and almost always valid for those of Beethoven and Weber:

![]()

After the death of the latter, ‘long appoggiaturas’ gradually disappear from notation altogether. Following Berlioz, none of the composers born in the nineteenth century, beginning with Mendelssohn, made much use of them any more. Even this brief overview shows how much of the theory of ornamentation was in constant flux.

The difficulty of working to clarify this increases further due to the fact that some composers of earlier epochs did not use their notation practices consistently.”

Let us hear what Franz Wüllner[10] has to say, in his revised edition of Mozart’s operas:

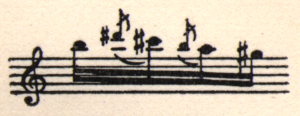

“In Mozart’s youthful works, we predominantly find sixteenth-note appoggiaturas—regardless of whether they precede a long or a short note. This sixteenth-note appoggiatura is always written like this, as was the custom at the time (not only for appoggiaturas, but for individual sixteenth notes):

![]()

The next example occurs very rarely in Mozart’s music, for example as the ‘completion’ after a dotted eighth note, but never before:

![]()

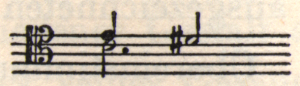

It should only be mentioned passing here that a frequently taught principle—that appoggiaturas with a line through them are short and those without a line are long—is based on a misunderstanding. The notation in the next example means that the appoggiatura has the value of an eighth note:

![]()

and this one has the value of a sixteenth:

![]()

In this respect, the first note is, of course, twice as long as the second. However, even a suspension executed as a sixteenth note can be what we call a long appoggiatura—if, namely, it is placed before an eighth note and has half the value of the principal note. Neither earlier nor later in his career did Mozart use a separate notation for short vs. long appoggiaturas, but rather wrote them using consistent note values (usually as sixteenth notes), leaving it up to the performers to decide whether to execute them as shorter or longer suspensions (taking time from the main note) or as short appoggiaturas in the modern sense (quick ornamental appoggiaturas).”

Wüllner adds that “the latter case” (i.e. short appoggiaturas) is very rare, and that most appoggiatura notes from that period were intended to be performed as long appoggiaturas.

From Engelbert Röntgen’s[11] remarks on the Urtext edition of Mozart’s violin sonatas, we finally learn that instead of the thirty-second note symbol, Mozart mostly wrote this symbol:

![]()

Cellists frequently violate this principles; here are some of the most frequently heard errors.

1. In the second part of the Allemande from Bach’s Suite in G major:

The appoggiaturas here are long, and the rhythm should have this stress:

2. In Haydn’s Concerto in D major, first movement, second measure after rehearsal C:

![]()

and also in the Adagio movement of the same concerto, in the second solo entry:

![]()

In both Haydn examples, the appoggiatura should be long, that is, it should take half the duration of the quarter note, otherwise the passage will sound angular and stiff.

3. In the Adagio of the Locatelli Sonata (fourth and fifth measures of the first and second sections):

![]()

The rhythmic division should be as follows:

4. In the first movement of Boccherini’s Sonata No. 6 in A major, Adagio section, the appoggiatura in the first measure should be shorter:

and the one in the second measure should be longer, like this:

and likewise in the sixth measure. Those in the tenth measure are probably supposed to be short; those in the eleventh measure are different. Here, it should probably remain a matter for debate whether the following appoggiaturas should be short or long.

The old edition in the Berlin State Library (probably dating from the end of the eighteenth century) records the passage in question as follows:

Perhaps the most tasteful way to interpret it would be as follows:

The appoggiatura before the note F-sharp at the end of the measure is undoubtedly short, as are the appoggiatura of the following (twelfth) measure. If one were to play them long, the execution would become quite uninteresting, because the following long series of sixty-fourth notes would create an impression of great monotony due to the proliferation of the same note values.

In measure 15, the appoggiaturas are to be played as follows: the first two long, the last short. Measure 16 contains a short sixteenth-note and a long quarter-note appogiatura. The latter is intended as follows:

In order to avoid the danger of monotony here, too, we recommend interpreting the suggestions of the next two bars as follows:

![]()

The first time, the appoggiaturas G-sharp, E, and C-sharp are short (in the Lombard style. The second time, they are long (in the old French style). The two E appoggiaturas in the second measure can also be interpreted differently, one time short, the other time long.

- Becker uses the term Vorschläge (singular: Vorschlag). This term can be used to mean "appoggiatura" or, more broadly, "grace note." I have chosen to translate Vorschlag as "appoggiatura" because Becker tends to use it interchangeably to encompass both the appoggiatura (in the present-day meaning of the word) and the acciaccatura (a term that he does not use at all), but not other types of grace notes. He occasionally uses the term kurzer Vorschlag (short grace note) to describe what we would understand as an acciaccatura in the present day. ↵

- Adolf Beyschlag (1845-1914), a musicologist whose landmark 1908 textbook on the interpretation of early music inspired early twentieth-century investigations of historically informed performance practice. ↵

- Becker's note: "Published at the instigation and under the responsibility of the Royal Academy of Arts in Berlin (Leipzig, Breitkopf and Härtel)." ↵

- Original: Beyschlag uses the terms Häkchen and Strichlein, meaning "little hooks" and "little dashes." These refer to the wavy and jagged lines used to notate certain types of trills and the S-shaped symbol for a turn. ↵

- Beyschlag's note: "We use the term 'short appoggiaturas' not only for those that are 'dispatched as quickly as possible,' but also those that are performed with some composure, should the style of the composition warrant it. In 1752, Quantz said of the appoggiaturas: 'It doesn't matter much whether [appoggiaturas] have more than one beam, or no beam at all. Mostly, they have just one beam.' Let the reader recall that 1720 marked Handel's first collection of suites; 1722 the Well-Tempered Clavier, book I; 1729 the St. Matthew Passion; 1741 the Messiah." ↵

- Friedrich Wilhelm Marpurg (1718-1795), a leading German music theorist and Enlightenment figure. ↵

- Beyschlag's note: "Since only short appoggiaturas were written, it was irrelevant how they were notated. But even earlier, some publishers' use of

was only apparently accurate; as a matter of business practice, they always printed the appoggiatura at half the value of the following main note." ↵

was only apparently accurate; as a matter of business practice, they always printed the appoggiatura at half the value of the following main note." ↵ - Johann Adam Hiller (1728-1804), a German composer and prolific author ↵

- Daniel Gottlob Turk (1750-1813), a German composer, professor, and author of several books on theoretical and pedagogical subjects. ↵

- Franz Wüllner (1832-1902), a composer, conductor, and editor for the Neue Bach-Ausgabe. During his lifetime, Wüllner was considered a leading authority on historically-informed performance practices. ↵

- Engelbert Röntgen (1829-1897), a German violinist and longtime concertmaster of the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra. ↵