On Dynamics

In the Mechanics section, we have discussed in detail how force affects the instrument, and have also often emphasized how the dynamics of the individual lever sections of the arm, hand and fingers work acoustically, and how carefully one must ensure that the muscular apparatus’s energy expenditure doesn’t exceed what is necessary.

With proper bowing technique, every intended nuance or accentuation becomes effortlessly achievable. As the touchstone of accomplished technique, the ability proves itself not only to sing beautifully in the cantilena, but also to play passages cleanly and with good sound quality.

The study of dynamics encompasses all levels of volume, from the most delicately breathed piano to the forte that pushes to the limits of possibility. Between these extremes lie not only the steps that are generally designated as piano, mezzo forte, etc.; but all possible levels of volume unite into a scale that, like a color band of the sound spectrum, shows imperceptible transitions.

Besides direct contrasts from forte to piano and vice versa, musical aesthetics recognizes dynamic tendencies, which are indicated by crescendo, decrescendo (diminuendo), and by accents. All these dynamic variants can be applied just as well to a single note as to a series of notes for expression. What freedom of nuance this gives the player, even when observing all the rules!…

A well-considered, sustained increase and decrease in dynamic power require absolutely steady bow speed throughout the phrase, as can be found, for example, in the first bars of Boccherini’s sixth sonata. The listener should be transported into a blissful, peaceful mood (A major!). Dynamic fluctuations, which all too easily catch the player unaware during bow direction changes and position shifts, should be avoided. The mechanics of bowing must be consistently balanced, so that there are no “holes” in the sound at any point. This is necessitated by the melodic line; every good singer performs phrases in this way.

Under no circumstances should the bow dictate the dynamics. One often hears the first measure of this movement played with emphatic accents on individual notes (see the discussion on portato). Such accents, which arise from deficiencies in technique, are a common bad habit. In solo performance and especially in chamber music ensembles, this manner of playing becomes tiresome and ultimately intolerable. The melodic line, which should flow according to the expression of the piece, must not be impaired by inconsistent dynamics.

It is different if we apply nuances wisely, as in the ascending scale in the second bar of the Boccherini work. This should be played rubato and should simultaneously decrescendo. Here, most cellists are tempted to make a crescendo just because it is played with an up-bow. This destroys the light, playful character of the figure.

Another example of combining rubato with a diminuendo can be found in Beethoven’s Sonata in D major, Op. 102 (for further explanation, see the section of this book on rubato).

In other places, an accelerando occasionally joins with a crescendo, particularly with ascending sequences, and especially when introducing a stormy development section. Besides proper dynamization of the arm, the economical use of the bow is essential here.

Capet bases his violin bow technique on the most precisely determined divisions of the bow. This relationship between metric proportions and bow dimensions, which is characteristic of the French school, cannot always be maintained when it comes to cello playing. It is precisely because of the need for sharp characterization in performance that one needs to understand intimately the expressive capabilities of the various parts of the bow.

If the goal is to develop such complete bow control that you can create accents even at awkward places in the bow, and to avoid having your dynamics suffer due to the natural differences between the weak tip and the strong frog, then it would be foolish for a player to ignore the advantages that different parts of the bow naturally offer. If there are technically difficult passages, particularly those requiring the parts of the bow that are innately better for certain demands, it is our task to sharpen the instinct for this through experience!

The proud Don Quixote theme, for example, requires a broad-sounding and energetic détaché that can be achieved neither at the tip nor at the frog, but in the lower third of the bow, with abundant bow changes and generous upper and lower arm movement.[1]

Even more than other bowstrokes, the spiccato demands a specific part of the bow. In the rapid, spontaneous movement of the so-called free-swinging spiccato, the balance point is the natural place to bow; in lighter, more delicate movements, it should approach the upper third of the bow (see the notes on Popper’s Dance of the Elves); in a martellato spiccato, it should be closer to the frog, as in the end of the first movement of the Dvořák Concerto at the fifth measure of the più mosso:[2]

The dynamic principle stands, as already mentioned, in relation to two factors: speed and pressure of the bow. Supporting elements include the degree of tilting and choice of bow position on the string. If the task is to simultaneously perform a series of connected notes on a down-bow with a consistent increase in dynamics, the player must use the bow economically at first, then use more as they approach the tip, as in this example (Dvořák Concerto, last movement, upbeat before rehearsal 13).

Through practicing difficult passages in various parts of the bow, the student should develop an instinct for the type of movement to use. This should help them instantly to find the right part of the bow for the intended expression. Even if it isn’t always successful, this sets them up well for sightreading.[3]

A particularly effective way to teach meaningful interpretation is with the help of words. It is beyond the scope of this chapter to trace all possible verbal relationships between beats and meters. We will cite just one of these striking cases where a word helps us avoid a senseless interpretation of a musical figure. In the following excerpt, we can sing the phrase to the words Voller Freude (full of joy) to illustrate its trochaic accentuation. Despite the fact that the accents are marked, one often hears an involuntary accent of the up-bow on the E-flat. Just add the above words to the notes, and the phrase will be correctly rendered.

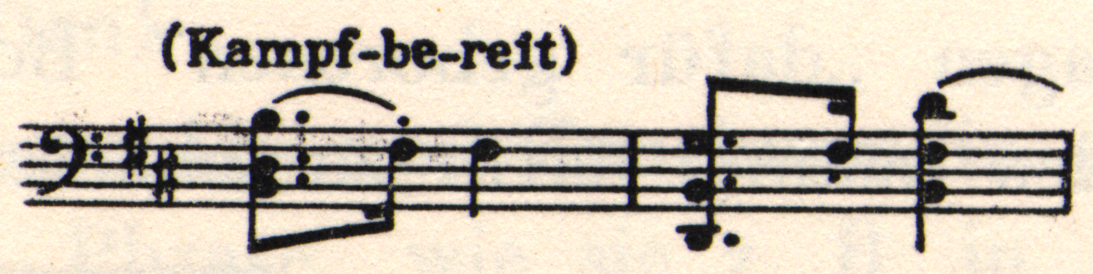

Another example, from the Dvořák Concerto, corresponds to the word kampfbereit (ready for war). The main accent in both measures should be on the chord, since these are dactylic rhythms.

However, there can be discrepancies in time. Accentuation is again closely linked to rhythm, since rhythmic structure requires correct accents. An example of this occurs in the main theme of the Saint-Saëns Concerto:

Here the first note E, although it falls on the weak beat, must be emphasized, while the second note falls on a strong beat that has been tied into. The emphasis is, in a sense, anticipated. A weak articulation of the quarter note E and an emphasis on the tied eighth note of the strong beat would be very inapposite. The charm of the phrase lies precisely in its metric displacement.

In the second measure, normal emphases fall on the first and seventh eighth notes. But the latter does not belong to a triplet: rather, it is a normal eighth note. The integrity of the rhythm therefore demands precise differentiation. The notated accent on the fourth quarter note of measure 2 is a special expression of the composer’s intentions.

In rhythmically complicated structures, we can’t manage with just one type of accentuation. For clear articulation we then use emphases of different degrees: alongside those of the most importance, we have less strongly emphasized ones. Such differentiation can be necessary, even with passages of rhythmically equal eighth or sixteenth notes (for example, the Prelude to Bach’s First Suite) or with dramatic passages such as this one from the first two measures of the Lalo Concerto.

In this passage, the E commands the strongest accentuation. Accents of secondary importance include the A and the second G, but they should be less emphasized. Through sensitive dynamic differentiation, we can clearly outline the character of these two measures, which decisively set up the character of the whole introduction.

The dynamics we use for accents are not just a matter of musical conception; they’re also tied to physical realities. However, the ways we express force on an instrument are only partially the result of physical processes. The connection between our physical movements and our mental associations—which are linked to emotionally-driven impulses—shows us that the inner sources of our musical force are influenced by psychological states, emotions, and feelings.

In practice, a musician’s personality is shaped by several factors: natural disposition, temperament, cultural background, and then the individual effects of intelligence, imagination, and finally environment—all of these form the foundation of musical personality.

Just as every language has its own accents and idioms, every nation has particular musical features. We can speak, for example, of “Slavic melancholy,” or “Germanic gravity,” or “Romanesque grace.” Such characters can be reflected in musical works. Just as every language has regional dialects that find expression in poetry, there are also folk melodies that put their own stamp on national musical cultures. Works of world literature are are not only the creations of different human minds, but of different regional temperaments, therefore their interpretation is dictated by the finest sense of style.

In the same way as dialects are different from literary languages—in which the masterworks of world literature appear—so one distinguishes folk melodies (such as Romani music) from the significant works of great masters infused with national elements from every country. Through their inner worth, elevated by the manner of their elaboration, beautiful creations first rise to the level of highest art.

So, if one wants to characterize melancholy romanticism in a Schumann concerto, the wistfulness and passion in one by Dvořák, and the colorful quality of a folk life bound to southern landscapes in the Lalo Concerto—to express what virtually jumps off the page—then the demand for striking characterization must not go so far as to transgress the boundaries of musical laws as determined by good taste.

- Becker's note: "See the notes on performing Don Quixote." ↵

- Becker refers to m. 333. ↵

- Becker's note: "The Frankfurt music director Karl Guhr, who had often heard Paganini, published a treatise entitled On Paganini's Art of Playing the Violin. In it, we find the following sentence: 'Reversing the laws of upstroke and downstroke, he played upstrokes with the downstroke and downstrokes with the upstroke.'" This book was published by Schott in 1830. ↵