On Intonation

To write exhaustively about intonation, we would have to be physicists, not musicians. Most reasonably educated musicians have some general ideas about tone production; anyone seeking greater enlightenment on the subject should refer to the classic work, On Tone Perception by von Helmholtz![1] There are also some high-quality works on the physiological processes involved in tone perception. For the practical musician, however, what matters most is training the ear. We have already noted that in most cases, poor intonation is caused less by clumsiness of the fingers than by imperfect understanding of how to judge pitch. The reason for this could be a lack of aptitude, or the neglect of proper ear training. We will disregard the former, since those who do not have the necessary ability should not play a string instrument!

Anyone who does not yet have a secure sense of pitch must first be instructed by impartial guidance!

Training the ear for clean intonation can be supported through various measures. First, we have an optimal aid at our disposal: the sympathetic vibration of the open strings. For example, when playing the note D on the G-string in fourth position, the open D-string vibrates sympathetically. By slightly adjusting the placement of the finger, the vibration from the resonating D-string will increase or decrease, depending on whether the finger moves towards or away from the physically correct point. Similarly, we can play an A on the D-string and observe the A-string vibrating in sympathy. When bowing a low D on the C-string, we notice that it is not only the open D-string that vibrates: the open A-string, as the fifth, begins to vibrate if the intonation is correct. Many such cases exist.

As far as acoustics are concerned, we primarily rely on comparison with open strings at the unison, octave, and consonant intervals. We can also consult the “Tartini tone.”[2] The learner should not expect a similarly strong, perceptible sound as the played notes. Rather, it is more like a soft, distant humming of deeper tones when two different notes are played (Riemann).[3] Although the combination tones are very weak, they have their own tonal structures, which can be developed through absolutely pure playing.

The tonal purity that we achieve in this way is absolute. We can recognize it not just by the pitch itself, but by the entire quality of the tone: its roundness, its freedom from impurities, its radiant brightness. In contrast to an absolute tonal purity is the relative purity of the piano, which many musicians prefer. The difference between absolute and relative tonal purity becomes evident in the so-called enharmonic substitution. An F-sharp and G-flat is, on the piano, the same pitch, but not on a string instrument.

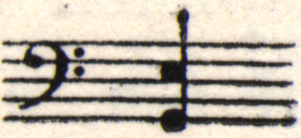

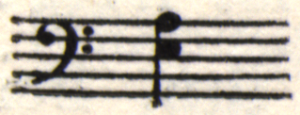

A brief detour into pure physics is permissible here: the problem of why E, in this example:

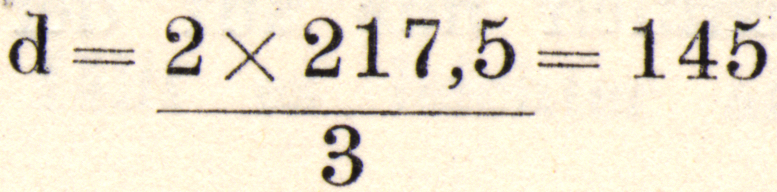

As is well-known, the feeling that an interval sounds pure is based on the fact that the frequencies of the respective tones are in simple whole-number ratios to each other. For example, concert pitch A with 435 vibrations per second corresponds to the note A on the cello with 217.5 vibrations per second, i.e. a ratio of 2:1.

Thus, in the octave: A : A’ = 1 : 2

Or, in the fifth: A : E = 2 : 3.

Accordingly, the D on the cello has 145 vibrations per second:

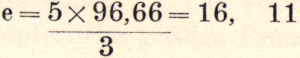

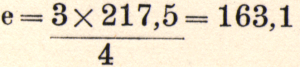

Conversely, if one wants to calculate E in the sense of the pure fourth below A, where A : E = 4 : 3, E will have approximately 163.1 vibrations per second.

Therefore, E must be higher if the fourth is to sound pure than if the sixth is to sound pure. Based on these considerations, we can conclude that the path to perfect intonation lies in comparisons with the open strings, observing the sympathetically vibrating strings, and paying attention to combination tones. These objective standards are the basis for studying intonation! It is also worth mentioning that in beginning studies, we should focus on the tones whose purity is the clearest to understand. The perception of tonal purity is similar to the perception of colors. As is well known, one cannot directly compare the sensations of two people; the color sensation of red can therefore only be tested for its intensity by comparing it with a scale of colors. The point of practice is to sharpen sensory perception and the ability to discriminate.

When practicing, one must take into account the increase in sound through combination tones. This is because some players, who previously played with poor intonation but were trained to study and perceive tonal purity, are initially struck by the greater intensity of sound. because some players who previously played impurely and were trained to perceive tonal purity through the study of intonation are initially struck by the greater intensity of the sound. In this respect, this person is like someone who suddenly steps out of semi-darkness into the bright light.

If, after prolonged and consistent effort, the student finally trains their ear to the degree of acuity necessary for playing with clean intonation, they may experience the subjective, depressing feeling that they are playing more out of tune than ever! This should not be cause for concern. It is only because they previously played out of tune while believing they were playing in tune. Now that the ear is more refined, even the slightest impurity of intonation sounds most unpleasant to them. This is a transitional phase and is part of progress. Right now, they perceive accurately but still play out of tune. To achieve pure intonation, it is necessary to establish an immediate connection between the ear and the motor functions of the hand. Instantaneously and without conscious thought, the finger can correct its position. Thus, we can conclude that playing “in tune” relies essentially on the constant improvement of previously incorrect playing.

- Hermann von Helmholtz, Die Lehre von den Tonempfindungen (Braunschweig, 1862). ↵

- Tartini tones, or combination tones, are the additional tone or tones that the human ear perceives when two "real" tones are sounded at the same time. Giuseppe Tartini (1692-1770) is said to have discovered the phenomenon. ↵

- Hugo Riemann (1849-1919), whose influential theories on functional harmony and acoustics still inform German scholarship. ↵