On Rhythm

Without descending into the depths of mystical speculation, we will make a brief attempt to give an idea of the significance of rhythm in music, and of the means of rhythmic musical formation. The educated musician will seek to grasp the essence of rhythm, not just from superficial familiarity with musical works, but through systematic study of the entire field of music theory.

Rhythm is primarily relevant to the temporal arts: dance, music, and poetry. In a figurative sense, rhythm also exists in architecture, sculpture, and painting, where it involves the rhythmic arrangement of adjacent masses or the depiction of arrested movement. Indeed, in a broader sense, we also speak of rhythm as an innate feeling—the human capacity to organize one’s life expressions into naturally flowing, regular patterns. (The rhythm of life.)

In general, rhythm represents orderly movement in time, as it also reveals itself everywhere in nature through the workings of the elements—in the surf of the sea, in the oscillation of the ether,[1] in the wave-like propagation of rays, in the circling of the stars. In organic nature, most movements, whether voluntary or independent of will, are rhythmically regulated—for example, the breath, the heartbeat, walking and running, the flapping of a bird’s wings, swimming. It seems that rhythm is the economically regulating principle to which all vital processes are subject, insofar as they involve an expenditure of energy and are essential for the individual’s existence. Thus, rhythm is closely linked with dynamics.

How deeply the rhythmic feeling is rooted in human nature is demonstrated by the experience that even across all levels of human society, all sustained activity is regulated in a rhythmic sequence (traditional dances, pulling and dragging loads, marching). The artistic expressions of earlier peoples were also characterized by the rhythmic structuring of their bodily movement to accompanying musical sounds.

In ancient Greek times, the three rhythmic arts—dance, music, and poetry—were united in a single artistic expression.

It is futile to investigate whether rhythm was truly present at the beginning or whether it developed later as a practical aid for physically strenuous expressions of life.

Maybe it is the expression of life’s feelings and life’s joys (dance, religious festivals, nature celebrations) led people to move rhythmically. In any case, the rhythm of music is something primal, something through which feelings and the soul are expressed in movement. We can accept Bülow’s words—that in the beginning, there was rhythm[2]—as a sure guarantee for music.

Definitions of rhythm:

Rhythm is the organizing principle that divides musical time into regular, predictable patterns (beat division). These time patterns are usually created by movements that repeat at equal intervals and are marked by accented beats, which help us recognize uniform time segments (like a conductor’s beat pattern). Alternatively, we can establish metric time units as the foundation of musical movement, where beats are organized according to their shortest note values (like setting a metronome). (In recent times, some musicians have moved away from strict beat division.) Along with audible dynamics and phrasing, proper rhythm helps distinguish artistic, expressive music-making from mechanical, robotic playing.

The choice of basic time unit (like whether to count in quarter notes or eighth notes) is always up to us. But once we have chosen that unit, it determines the tempo—i.e. the speed of the music. This lawful, consistent execution provides the crucial foundation for all musical design: the rhythmic mastery of a piece. There’s no worse musical distortion than choosing a tempo where the main beats stay rhythmic but fast passages and ornaments get bogged down by hesitation and delays. It is equally bad when fingers run away due to lack of rhythmic control.

All expressive freedom in music finds its natural boundary in strict adherence to the established rhythm. But rhythm also provides our strongest support for technical security in performance—as long as we put rhythm first from the very beginning of practice, making sure every sequence of notes, every bow stroke, and every fingering follows rhythmic patterns. Let us consider rhythm as a teacher!

This way, rhythm becomes an integral part of our physical movement sense. What becomes automatic through long, rhythmic practice becomes a reliable skill we can count on during performance.

All performing arts create their strongest impact on audiences by seamlessly integrating technical challenges into the music’s rhythmic flow. Our emotions, temperament, and expressive powers are also bound up in rhythm. From the chaos of unorganized feelings emerges rhythmically flowing, uplifting melody supported by harmonic foundations, organizing the harmonic structure of individual voices into a polyphonic whole.

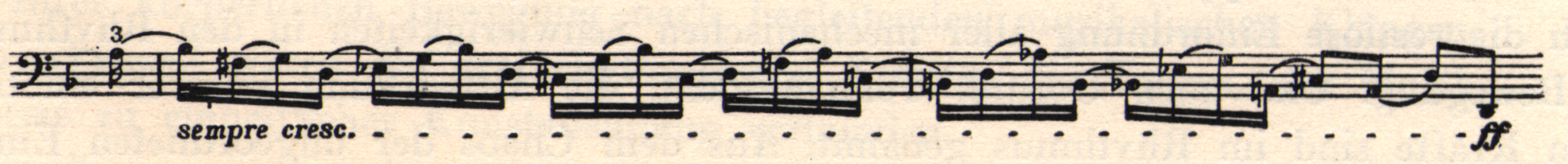

Rhythm has two kinds of meaning. In the narrower sense, it regulates the relationship of note values within individual beats. Here, the accented, or dynamic emphasis of individual notes is the means of organic organization.[3] In the broader sense, it regulates the flow of entire beat groups within the larger structure of a movement. Here too there are fixed rules: the intensification of musical expression, whether in the sense of a dramatically animated build-up of the musical event, or as logical development from themes to a climax, creates an acceleration of the time measure, that is, a rhythmic intensification. We will see that this intensification, which is marked with accelerando (or stringendo) and occurs frequently, but by no means always, is connected with a dynamic intensification, and stands under the compulsion of a lawfulness (Dvořák Concerto, p. 12, second system).[4] An example of how an accelerando can also be combined with a diminuendo is provided by the small cadenza of the Saint-Saëns Concerto, p. 5, second system.[5] Here the racing motion of the movement, the accelerando, expresses the transition from an emotionally emphasized passage into a playful arabesque.[6]

When the accelerando is applied as a nuance within a small figure (Haydn Concerto, first measure after E),[7] it involves agogic differentiations!

Another function of rhythm is the ritardando: it is often (though by no means always) connected with a dynamic weakening; while the accelerando has the character of urgency, pressing forward, or of a situation becoming more intense, the ritardando suggests reflection, holding back, hesitation, consideration (Dvořák Concerto, p. 2, the one-measure transition into Tempo I, which is the same in the recapitulation).[8]

The ritardando can also be combined with a dynamic intensification to work toward a climax (Dvořák Concerto, p. 7, last system, trill, intensification in the orchestra).[9]

Accelerando and ritardando are subject to lawful development. Just as a body set in motion gains its full speed only gradually, so must the intensification of tempo in music also proceed logically. That is to say, the time interval between two successive notes within the note sequence should become smaller in lawful development.

With increasing speed, every body gains greater living momentum (kinetic energy). The dynamic intensification should usually proceed in the same proportion as the rhythmic (see Reger’s Suite in D minor, Präludium):[10]

Here are some common “violations” that distort the meaning of a piece by combining expressive changes in ways that go against the composer’s wishes. (As stated above: an accelerando doesn’t always need to be connected to a crescendo, and a ritardando doesn’t always need to be connected to a diminuendo!)

Think of ritardando as a body losing momentum—its movement gradually slows due to constant frictional resistance. (For example, a railroad car that has been pushed away from a moving locomotive.) A bouncing rubber ball provides an excellent image for understanding motion. As the ball continues to fall, energy loss causes it to bounce increasingly slower.

Applied to music, this would result in an accelerando with a concomitant diminuendo. Imagined in reverse, this is an example of a ritardando and crescendo. The buildup of an avalanche is comparable to a crescendo and accelerando. The effect of a ritardando is almost indistinguishable from a ritenuto, but there is a fundamental difference between animato and accelerando, which is unfortunately often misunderstood.

Unlike rhythmic changes that involve uniformly continuous speeding up or slowing down, some tempo changes begin immediately at a new speed—namely animato and the opposite meno (meno mosso or più moderato).

Animato signals the heightened energy we feel when encountering events that move us more deeply, at a faster pace (e.g. in the first movement of the Saint-Saëns Concerto). The meno or più tranquillo, on the other hand, is intended to slow the flow of the narrative; it can be used both to calm the narrative or to highlight the significance of a passage, to emphasize something musically important. Sostenuto creates a similar effect. Sostenuto means “sustained” and should not be confused with ritardando (for further explanation, see the section of this book on sostenuto).

Within each measure, rhythmic structure emerges through emphasizing certain beats that traditional meter and rhythm rules deem musically important. The notes of the so-called strong beats of the measure are clearly accented. Accents in the true sense (that is, marked accents)—these terms must be clearly distinguished—are stronger dynamic accents of individual notes; they are expressed by the symbols sf or > (or erroneously, v!) and should not be confused with the gentler dynamic accents (better described as emphases), which are dictated by the rhythm and determine the character of a musical work (3/4 time in a waltz, march rhythm, etc.). However, we cannot arbitrarily change the duration of these emphasized notes; they must follow agogic principles. Meaningful musical interpretation only emerges through properly combining dynamic and agogic emphases within the measure’s rhythmic framework.

The fundamental principle that accents should be made according to the musical structure (though without metrically distorting the beat pattern) allows us the greatest freedom in shaping within the overall movement (Bach Suites! For example, the Prelude in D minor):

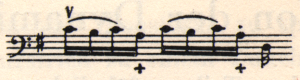

When, as here, dynamic and agogic accents coincide, the integrity of the rhythm must be preserved by maintaining the time duration of the note (for further explanation, see the section of this book on agogics). Upbeats can take on the character of negative accents, as the following example from the Gigue from Bach’s Suite in D minor shows:

Despite the dot over an upbeat note, the time duration prescribed by the note shouldn’t be shortened—rather, the abbreviated tone should be supplemented by a following pause so that the full time value is maintained. Such pauses are often applied to dotted notes to benefit rhythmic integrity (Volkmann Concerto, page 1, 7th system;[11] Dvořák Concerto, page 1, third system).[12] Beyond the accents that are typically applied to downbeats and upbeats according to established rules—those described as strong beats (i.e. emphases of the first beat of the measure)—further emphases within the same measure are often needed to clarify the rhythmic structure[13] or for other musical reasons (compare the analysis of the first Bach Suite—see also Riemann’s Metrik).[14]

*

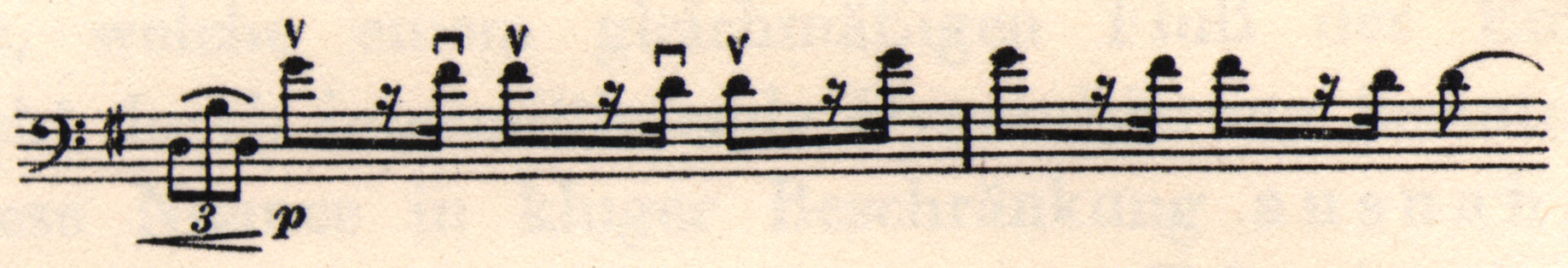

Here I should insert a comment about the connection between rhythmic accentuation and bowing technique, which has fundamental importance for performance and unfortunately causes distortion in practice all too often (not just in practicing, but sadly also in public performance) in the most valuable works in our literature. If we were to prioritize the mechanical characteristics of the cello, then all accents would have to be played with the down-bow and all crescendi with the up-bow. However, would not apply such a one-sided approach, since it would be incompatible with the design of the work.[15] In phrasing, we would be obligated to make constant concessions to this demand. All too often, a situation arises where a note’s emphasis doesn’t coincide with the down-bow, but with the up-bow. If we are unable to play in accordance with the composer’s musical intention vs. the peculiarities of cello mechanics, we deprive ourselves of the tonal nuances that so enliven a performance. For example, in this passage from the third movement of Brahms’s Sonata in E minor:

Or in this one, from the Courante of Bach’s First Suite:

The Prelude to Bach’s First Suite offers another suitable example: how imperfectly we would achieve the crescendo occurring in the bars of the sixth, seventh, and eighth system (p. 5)[16] if we took the melodic notes above the sustained A pedal on a down-bow! Our sense of the subtlety of sound and movement should prevent us from doing this. It is therefore better to choose the upbow for this passage, starting at the tip and and steadily increasing the amount of bow so that we finally use the entire bow. At the same time, however, we constantly minimize the sound of the open A-string, dynamically speaking, even though it falls on the down-bow.

We achieve the diminuendo by gradually reducing the amount of bow used. Conversely, we play the accented notes of the last measure of the third-to-last system[17] with a down-bow. The bowing direction in this case is determined by the tonal concept; melodic notes played on an up-bow can be produced more delicately, while with the opposite bowing direction, the crescendo is more pronounced. To create variation, the two types were contrasted. In the first case, the crescendo extends over a longer period of time (see the performance analysis of Bach’s Suite in G major).

- By "oscillation of the ether," Becker refers to luminiferous ether, which was a theoretical substance that nineteenth-century physicists believed filled all of space and served as the medium through which light waves traveled. ↵

- Becker quotes a motto attributed to the conductor Hans von Bülow (1830-1894), "Im Anfang der Rhythmus war." ↵

- Becker's note: "We distinguish between dynamic and agogic accents, but use both for melodic and harmonic emphasis (see Riemann)." ↵

- Becker refers to a section the third movement of this work, rehearsal 4, marked Poco meno mosso. ↵

- Becker refers to the Durand edition of this work. The cadenza he describes begins at m. 297. ↵

- Becker's note: "Compare the lecture analysis of the Saint-Saëns Concerto on p. 234 [i.e. later in this section of the book]." ↵

- Becker refers to François-Auguste Gevaert's edition-arrangement of Haydn's Concerto in D major, first movement, m. 50. ↵

- First movement, m. 157. ↵

- First movement, m. 341. ↵

- Max Reger (1873-1916), Suite No. 3 in D minor, Op. 131c. ↵

- Becker refers to his own edition of this work. The passage described starts at m. 39 of the first movement. ↵

- Becker refers to mm. 94-96 of the first movement. ↵

- Becker's note: "We distinguish rhythmic, melodic, and harmonic accents." ↵

- Hugo Riemann, System der musikalischen Rhythmik und Metrik (Breitkopf und Härtel, 1903). ↵

- Becker's note: "See the footnote in the next section about Paganini's characteristic use of accents on the up-bow." ↵

- Becker refers to mm. 31-36 of his own edition of Bach's Cello Suites. ↵

- Becker refers to mm. 37-38. ↵