On Rubato

A chapter on the art of interpretation would be incomplete[1] without an aesthetic consideration of rubato playing.

Despite the concessions we must make to individuality in the interpretations of talented people (for we can justify subjectivity in music), we must not forget that the history of rubato playing already contains so many examples that it saves players the effort of trying everything ourselves, providing we are familiar with historical developments in rubato.

Let us first familiarize ourselves with the historical origins. The first mention of the term is found, according to Kamiénski,[2] in a singing textbook from 1723 by the then-famous singing teacher Pierfrancesco Tosi.[3] Since Tosi speaks of the already well-known practice of rubare il tempo (“robbing time”), one may assume that rubato emerged in the seventeenth century, or the beginning of the eighteenth. Tosi refers repeatedly to a great singer named Pistocchi,[4] whom he calls an immortal musician and whose perfect taste he praises, saying that he brought forth the beauty of the art of singing without injury to the time. In his chapter “On Cadenzas,” Tosi speaks about the indispensable embellishment of interpreting arias. This involves “strolling along” (andare) according to the movement of the bassline, improvising ornaments that stick to the regular measure or take time at one’s own discretion. “Whoever does not understand rubare il tempo would not know how to accompany, and would lack the most refined taste.” Immediately after this, he says perché l’intendimento e l’ingegno ne facciano una bella restituzione (in translation: “provided that understanding and ingenuity can restore the robbed time in a beautiful way”). This remark tells us that rubato was only accessible to singers who were familiar with the theory of realizing basso continuo. It presupposed a high level of creative ability. It consisted of a rhythmic reshaping of the vocal line within a given tempo without changing it. The melodic changes, however, were already indicated through appoggiaturas and passaggi. Especially in arias full of pathos, rubato was appropriate performance practice. Briefly put, what the aforementioned historical documentation of rubato demonstrates is a rhythmically free treatment of a vocal line without changing the inherent pulse of the bassline.[5]

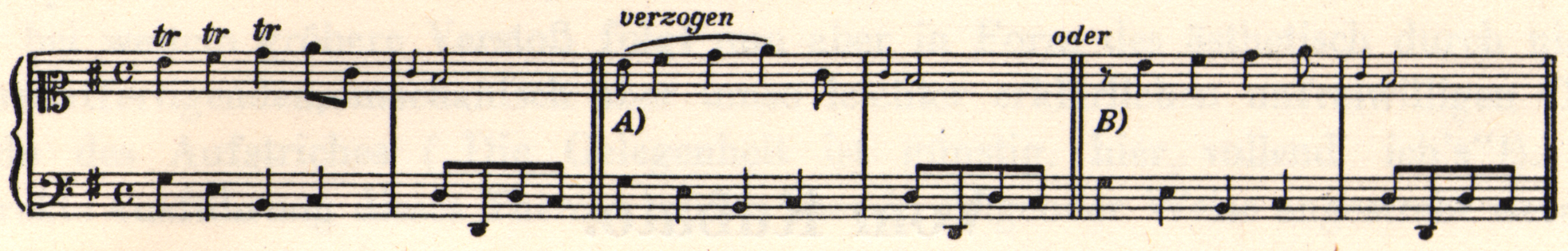

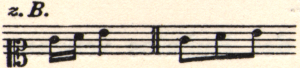

In arias, especially those of pathetic character, it was customary to shorten a note value by gliding from note to note without affecting the overall tempo. For example:

Further examples show the simple syncopation:

The anticipation of the beat:

and

Further formations, such as these:

Also, the reversal of these examples in such a way that rhythmically restless figures are smoothed out, giving a rubato effect, for example:

Or, in the popular Lombard manner:[6]

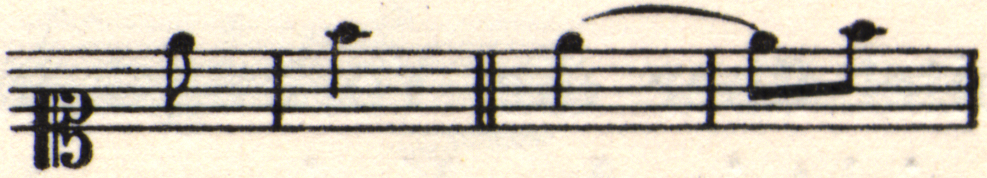

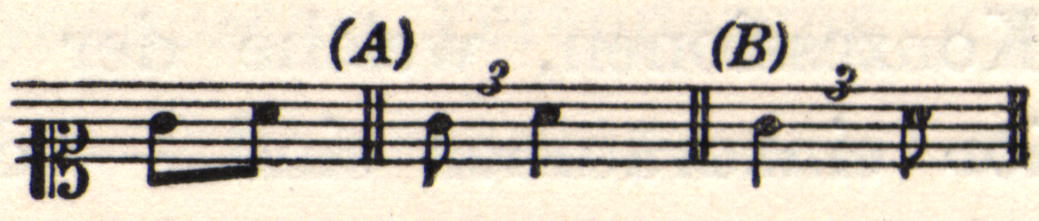

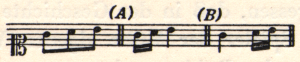

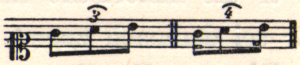

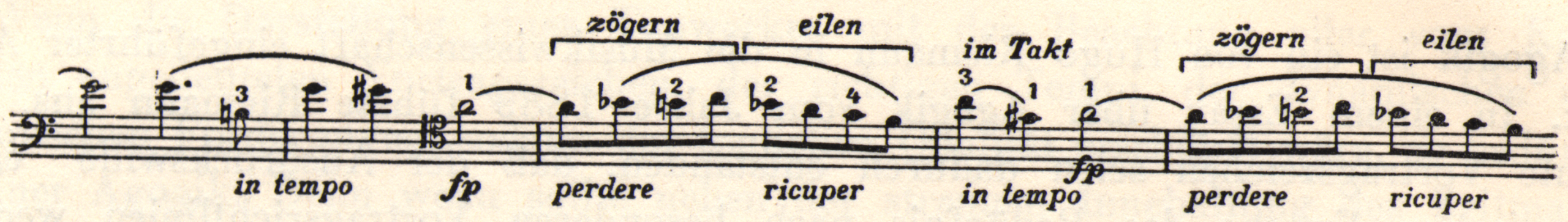

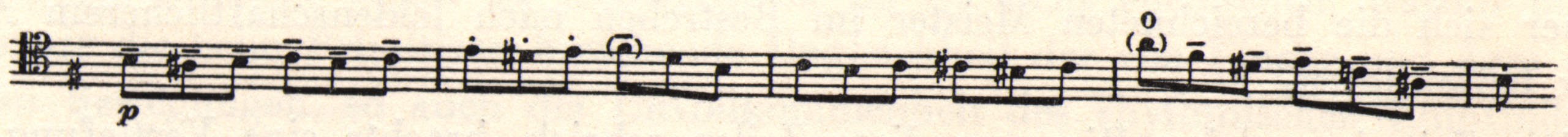

Kamiénski, rightly recognizing that the rhythmic fluctuations of such embellishments are too refined for exact notation, says: “The abundance of possible rubato variations is neither exhaustive nor exhaustible, since it concerns irregular inflections that we can hardly capture in notation.” However, to gain some conception of how to create a rubato, let us use the example of a simple scale-like figure to demonstrate some possible alterations. Naturally, this cannot precisely determine the note values (otherwise a composer could notate them from the outset!), but rather provides general guidelines.

The imitation and development of rubato as a performance practice in subsequent periods may have involved playful processes of perdere per ricuperare[7] and guadagnare per perdere,[8] but the original intention of its inventors was certainly the desire to intensify emotional expression. And this is where modern music picks up again, combining the intermittent increase and decrease of tempo with a retention or intensification of an affect; that is, the “loss” and “gain” of time are connected with a stringendo-calando or calando-stringendo.

The older Italian school (whose principles lasted, despite many changes, up until the time of Chopin) indicates special consideration of the bassline movement, which carried the tempo and thus should not be altered. The bassline represents the unyielding rule from which the individualistic melodic line (the domain of the singer or instrumentalist) deviates. If the melody sometimes deviates from the beat, rubato does not suspend the fundamental bassline movement, but rather heightens the sensation of contrast with the tempo. Rubato, as a kind of rhythmic freedom of expression against an unaltered ground bass, continues into modern times. From this historically informed viewpoint, we should no longer speak of “stolen” or “robbed” time, but rather of “time-taking,” with the with the complementary idea of restituzione, the restoration of what we took from one note to another note. We should call it more of a “rhythmic melodic ornamentation.”

It is remarkable that Quantz,[9] the informative theorist of the eighteenth century, does not mention rubato. This may be because by his time, there was a deliberate effort to rein in the excessive use of rubato. [Carl] Philipp Emanuel Bach also writes little about rubato, mentioning it insofar as he recommends using a good singer as a role model for rubato in slow movements. On rubato playing, Leopold Mozart writes: “A skillful accompanist must not yield the beat to a truly competent virtuoso, as he would otherwise spoil the soloist’s rubato; however, when dealing with a pretentious virtuoso who lacks real skill, the accompanist might as well sustain whole eighth notes for the duration of a half measure in an adagio cantabile, waiting until the soloist recovers from his fit of self-indulgence—nothing this person does follows the beat properly, since he plays everything like a recitative.” (This last part is meant ironically). Leopold’s son, the great Wolfgang Mozart, reports quite clearly in a letter to his father: “That I always stay precisely in tempo surprises everyone. What they can’t understand is that when I play rubato in adagio movements, the left hand maintains steady time and does not participate in it.”

The highest development of rubato is achieved by Chopin, who—in subtle and often quite far-reaching performance indications—only hinted at rubato playing.

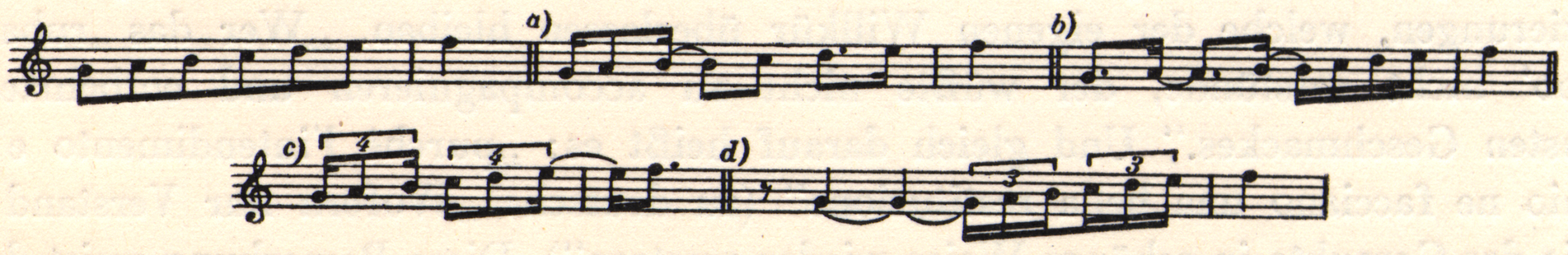

Guided by the idea that every measure must correspond to an emotional impulse, we will now try to quote some passages from our cello literature.

In the Prelude to Bach’s Fifth Cello Suite, the lines marked under the staff correspond to the relative lengths of the notes when played rubato (see further explanation below).

The rhythmically counted quarter note C that is tied to the sixteenth note C represents the character and tempo of the measure. The sixteenth-note figure grouped under the following slur represents a development that leads to the rhythmic landmark of the second measure:

We should use rubato in a sensitive manner, in the spirit of an intensification of expression. The transition from a state of repose into that of urgent movement is created through what the old masters called perdere per ricuperare.

In the knowledge that notation cannot precisely express the way rubato works, we have illustrated it differently in the following graphic representation of the passage, in which the lines represent time values:[10]

![]()

![]()

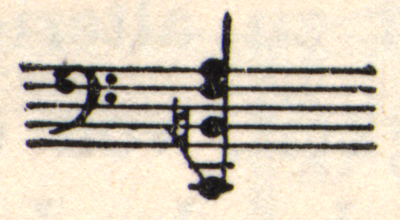

Similarly, the third-second notes in m. 9 of the Allemande in the Second Suite should be treated like this:

The preceding suggestion is just one of many possibilities, but is nevertheless one of the most commonly used in performance.

Here is another example, from the Adagio of Beethoven’s Sonata in D major, Op. 102:

Here, the group of notes beginning on the tied G would be rubato. The G is prolonged; then, we blend into the tempo when the piano takes up the melody.

From the same sonata:

The particular pathos of this passage demands very free declamation and great warmth. Hold the first thirty-second triplet note somewhat, and then play the following two more urgently! Play with great expression on the high D; then use portamento to get to the A. Make up for the lost time until the emphasize notes C and B. Then do the same thing for the next pattern in the sequence.

In the second Gavotte of Bach’s Suite in C minor, we can place a rubato over several measures: 2

The phrase marked with the bracket can be peaceful and expressive. Then we become faster and more animated.

A further example can be found in the Schumann Concerto. At the cantilena in the beginning of the development section, play rubato in this solo passage:

Here, a strict measure is followed by a rubato measure, in which we delay in the first half, then play the second half in a rushed manner “compensate.”

In the following passage from the third movement of Brahms’s Sonata in F major, the circled notes represent “targets” for the preceding triplet figures. Since the target notes themselves are only components of eighth-note triplets, we should only emphasize them with agogic accents (i.e. a slight lingering), not with dynamics. To avoid playing the triplets in the manner of an etude, we should play using rubato.

From these examples the concept of rubato emerges clearly. Rubato permits freedom of delivery without abandoning the underlying beat. One can certainly interpret the above passages differently, provided one can make a proper musical justification for doing so. For rubato must not be based on a vague feeling, but rather the intention to give vivid expression to a musical text. Of course, those who are knowledgeable will eliminate many of the possibilities as going against musical good taste—to do otherwise would be impossible!

- Becker uses the expression ein Torso bleiben ("remain a torso"), implying that omitting rubato from a discussion of interpretation would be as incomplete as a statue with only a torso and no arms or legs. ↵

- The eminent Polish musicologist Łucjan Kamieński (1885-1964). ↵

- The Italian castrato singer, composer, and writer on music Pier Francesco Tosi (ca. 1653-1732). Tosi's 1723 book Opinioni de’ cantori antichi e moderni remains an important primary source for the historically informed performance of early music. ↵

- The Italian castrato singer, composer, and librettist Francesco Antonio Pistocchi (1659-1726).( ↵

- Becker's note: "[Johann Friedrich]Agricola, the German interpreter of Tosi who lived a generation later, illustrates rubare as follows: 'To distort the notes, rubare il tempo, actually means to take away some of the significance of a prescribed note in order to add it to another, and vice versa.'" ↵

- The Lombard rhythm, also known as the Scottish snap or a "long-short" rhythmic figure. ↵

- "Lose to recover" ↵

- "Gain to lose" ↵

- Johann Joachim Quantz (1697-1773), the flutist and author whose Versuch einer Anweisung die Flöte traversiere zu spielen (On Playing the Flute, 1752) remains one of the most important treatises for historically informed performance practice. ↵

- In German musical notation, H is B natural and es is E-flat. ↵