On the Diversity of Timbres, with Special Consideration of the Open A-String

Just as the composer works on instrumentation and the organist pulls out stops, so too can the cellist produce different tone colors on their instrument. By this we do not mean the almost inexhaustible possibilities for dynamic gradation, but more specifically the color of the sound.

The four strings form four different registers, which the skilled player can easily exploit for an intelligent, varied performance by striving to play the coherent parts of a phrase on the same string, if possible. However, it will be more difficult to achieve homogeneity of tone between the registers if a passage crosses over two (or more) strings and one of the notes we need to play is the open A-string. It is important to be sensitive to this, and to create balance through applying appropriate dynamics to the individual pitches so that there is unity across the register.

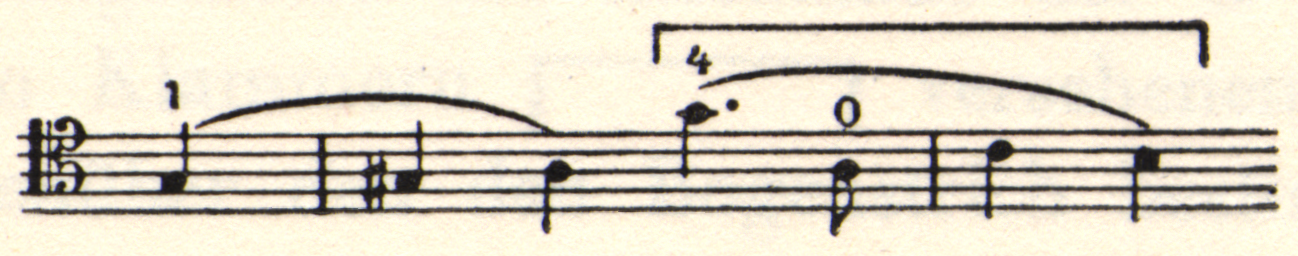

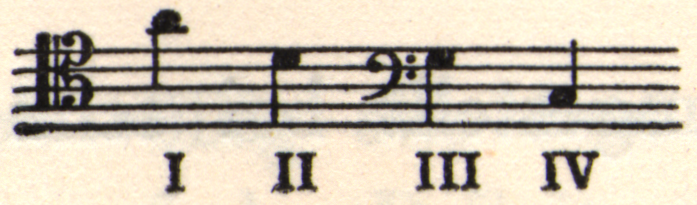

There are cases when crossing to another string is impractical and sounds unattractive, such as when it is for only a few (one or two) notes. A good example of this can be found in the second theme of the first movement of the Schumann Concerto. When the theme appears in C major, one can play the entire phrase (marked with a bracket) on the A-string.

But when it appears in A major, only the E falls on the A-string:

This would sound completely out of place; therefore, we usually play the entire theme on the D-string:

As is well known, it is best to avoid using the open string in cantilena passages wherever possible, since otherwise the uniformity of tone in that register would suffer. This refers particularly to the open A-string, which sounds brighter than the lower-pitched strings. Nevertheless, the cellist should try, through skillful use of the bow, to adapt its tone color to better match that of the surrounding pitches.

This finely differentiated handling of the bow sometimes even allows us to break the aforementioned rule without damage if context demands it, as we show in at one point in the analysis of the Dvořák Concerto.

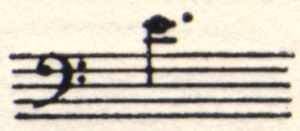

Naturally, we need considerable practice to achieve such complete mastery of the bow and refinement of the ear. Exercises like the following can lead to the desired goal. One would play this phrase first in the second position (third finger on G♯), and then in first position using the open A-string:

The student should now direct their effort toward matching the tone color using either approach, so that the listener can barely tell the difference between one fingering and the other.

Here is a similar example from the second movement of the third movement of the Locatelli Sonata:

By acquiring such skill, the player will also be able to play passages such as this one (from the first movement of Beethoven’s Quartet in C major, Op. 59, No. 3), in two ways, without necessarily giving preference to one or the other as regards the smoothness and uniformity of the figure.

However, in both cases, the bowing should be arranged as indicated. Also note that if you choose the fingering below the staff, the bowstroke should begin at the frog, while with the fingering above the staff, it begins in the middle so that the notes A and G can be played with great smoothness at the tip of the bow over the string crossings.

Overcoming anything that might disrupt the tone is one of the main aspects that define a player’s artistry.

There are also cases, however, where using the open string would be less disruptive. Indeed, there are even some where using the open string would support the composer’s intended effect.

For example, let us imagine the motive above rhythmically rearranged at a faster tempo, with energetic expression and a forte dynamic:

In this version, the open string supports the desired expression.

For the same reason, we recommend using the open A-string in this sixteenth note passage of the d’Albert Concerto (page 3, eighth system), because of the accent falling on A.

Should circumstances force the player to use the open A-string during an expressive cantilena at a slow tempo, they can produce an effect similar to vibrato by gently tapping on the sympathetically vibrating D-string with an inactive finger of the left hand. In this way, we establish uniformity of tone.

In the two following passages, both from the first movement of Beethoven’s Sonata in A major, it would make no sense to choose fingerings other than those shown.

![]()

Similarly in the first of Schumann’s Pieces in Folk Style:

The same objection arises if a player were to play an open A-string on the second eighth note of measure 7 in the first movement of the Locatelli Sonata. However, we usually hear it like this, and it creates a false emphasis on the A.

![]()

Also, in the following passage (from the third of the present author’s Spezial-Etüden, Op. 13), the string crossing to the open A-string is initially quite fitting, since the expression calls for a sonorous sound. At a piano dynamic, this is not the case, and we must avoid the open string.

Certain notes also demand greater attention, such as natural harmonics:

However, harmonics should not be used habitually when playing cantilena passages, because the tonal homogeneity of the phrase would suffer. The random interspersing of natural harmonics usually occurs only for reasons of convenience. Here, too, the player should observe the guiding principle that ease of execution must be sacrificed for the sake of beauty.