On the Dynamics of the Bow Hand

Anyone who takes the idea of the hand as a “unit” and turns it into something heavy-fingered and effortful will actually scatter the force instead of focusing it. This weakens tone production. As stated earlier, when the fingers work properly, they do not weaken the tone, they actually help to enhance it.

The forearm’s capacity for leverage works most effectively in the so-called middle position. Therefore, for the optimal application of force during changes of bow direction (especially during string crossings), do not make excessive use of the longitudinal rotation of the forearm. In other words: extreme rotation (i.e. the extremes of pronation and supination) should be avoided. This becomes possible if we involve the fingers when changing bow direction. The double lever action—bending and stretching the fingers, as well as a less noticeable but very important sideways movement in metacarpophalangeal joints— this elasticity is exactly what facilitates the development of a powerful tone.

You can properly assess the activity of the fingers by understanding them as levers that primarily transmit the forces of the forearm muscles, while the short metacarpophalangeal and thenar muscles assist through bending of the finger segments and stretching of the end segments.

When, however, the fingers clamp down and curl tightly around the stick, bending and locking at the knuckle joints in an excessively tight grip, the hand can no longer function as a flexible unit. Instead of the coordinated system of forces working together, only one rigid force operates. The bow is locked rigidly to the forearm, and the inevitable results include getting “stuck” during bowing, jerking and clumsy string crossings, and uncontrollable flailing of the forearm.

The hand’s function as a flexible “unit” works in two different ways depending on bow speed: in slow bow movements, the hand actively participates in controlling and shaping the motion; in rapid bow movements, the hand works more reactively, flexibly responding and guiding the motion rather than trying to control it.

The function of the “artificial joint” can be twofold: in slow bowing movements, it acts more independently (active), while in faster movements, it serves more as a conduit (reactive). The curved, active configuration of the hand must always be maintained, just as the wrist joint should never be bent too strongly, because this causes us to lose force (especially at the tip). See image 9 in the Appendix.

The faster the change in direction of the bow, the more carefully we must manage the balance between wrist, forearm rotation, and finger motion.

Precision in bow technique depends on coordinating movements correctly and applying the right amount of force (whether you’re working actively or reactively).[1] Generally, when playing fast sixteenth-note passages, the fingertip control and the hand’s oscillating movement work together so well that the movement patterns learned during bow changes become more obvious.

When playing spiccato (or détaché-spiccato) across three strings, your bow hand needs greater stability for certain passages to get the right bow bounce on each string. In these cases, you can replace the finger lever action with forearm rotation (pronation and supination).

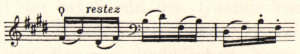

Example from the first movement of the Valentini Sonata:

We have seen that forces applied to the bow work in two ways. First, the index finger and little finger move independently against the resistance of the thumb. Second, the forearm rotates lengthwise while the index finger and little finger transfer this rotation to the bow without changing their positions.

We use the second method for passages like this:

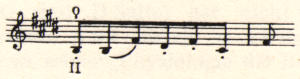

Here, the crescendo needs a flowing bow stroke with plenty of arm movement. Forearm rotation works perfectly for this style of bowing. Near the frog, independent finger lever action helps to create a particularly expressive character. Here is an example from the last movement of the Valentini Sonata:

This shows how to use the momentum from the weight of the hand. These passages often use tremolo stroke (first and last movements, plus the second system on page 5[2]). We can create the accented single and double-stopped sixteenth notes through hand momentum with sudden but light impulses from the forearm!

Détaché near the frog always requires significant restriction of wrist activity. We must emphasize here that when playing détaché in the lower third of the bow, the movement originates from the shoulder (see the section on the détaché stroke).

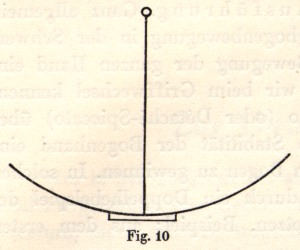

Fig. 10

It is better to avoid all wrist and finger movements than to avoid arm movements in the shoulder joint. To pull the bow straight near the frog, we need to use the “long pendulum arm.” The trajectory of the bow becomes much straighter this way. (See Fig. 10 and also the section on the détaché stroke.)

Here too, to avoid stiffness, the rule applies that during rapid bow direction changes, you should limit big arm movements and let the smaller parts of the body (hands and fingers) take over the movement in a timely manner.

The bow hand movement that we will describe later (in the section on changes of bow direction) is a simplification of the movement sequence. For short, stopped bowstrokes at quieter dynamics, this movement can even be limited to just the fingers (see the section on finger strokes and their variations).