On the Physiology of Bowing

Bow technique is the natural outcome of movements that follow consistent patterns while being continuously adjusted in real time.

There are not many fundamental works where one can recognize the individual moments in bowing on the cello, as well as the various phases and dynamics of the movement. Those who wish to fully understand the visual material of this book, which comes predominantly from a motion picture and thus repeatedly represents reality, would do well to at least familiarize themselves with the main physical and physiological concepts. In addition to the work by Steinhausen from 25 years ago, The Physiology of Bowing on String Instruments, there newer works dealing with this subject. Deserving of special mention are The Fundamentals of Natural Bowing on the Violin by Arthur Jahn,[1] as well as the book The Natural Fundamentals of the Art of Playing String Instruments by Trendelenburg.[2][3]

Let us first consider the arm and bow as a moving system!

The movement of the bow and arm kinematically represents a combination of so-called elementary movements, whose two components are elementary linear movements and elementary rotations. During a linear movement, the body moves so that all its points describe parallel and congruent paths; during a rotation, all its points describe circles whose planes are perpendicular to a straight line that simultaneously contains the center points of all circles. Through the combination of both movements, a so-called elementary spiral motion arises. All movements of the bow-arm are spiral motions, because the following conditions of bowing must be met:

- The bow must always be pulled perpendicularly to the string, or (in what is essentially the same thing) must always be placed on the string at a right angle.

- So that the bow always touches only one string, it must be moved in a direction that results from its extension toward both sides.

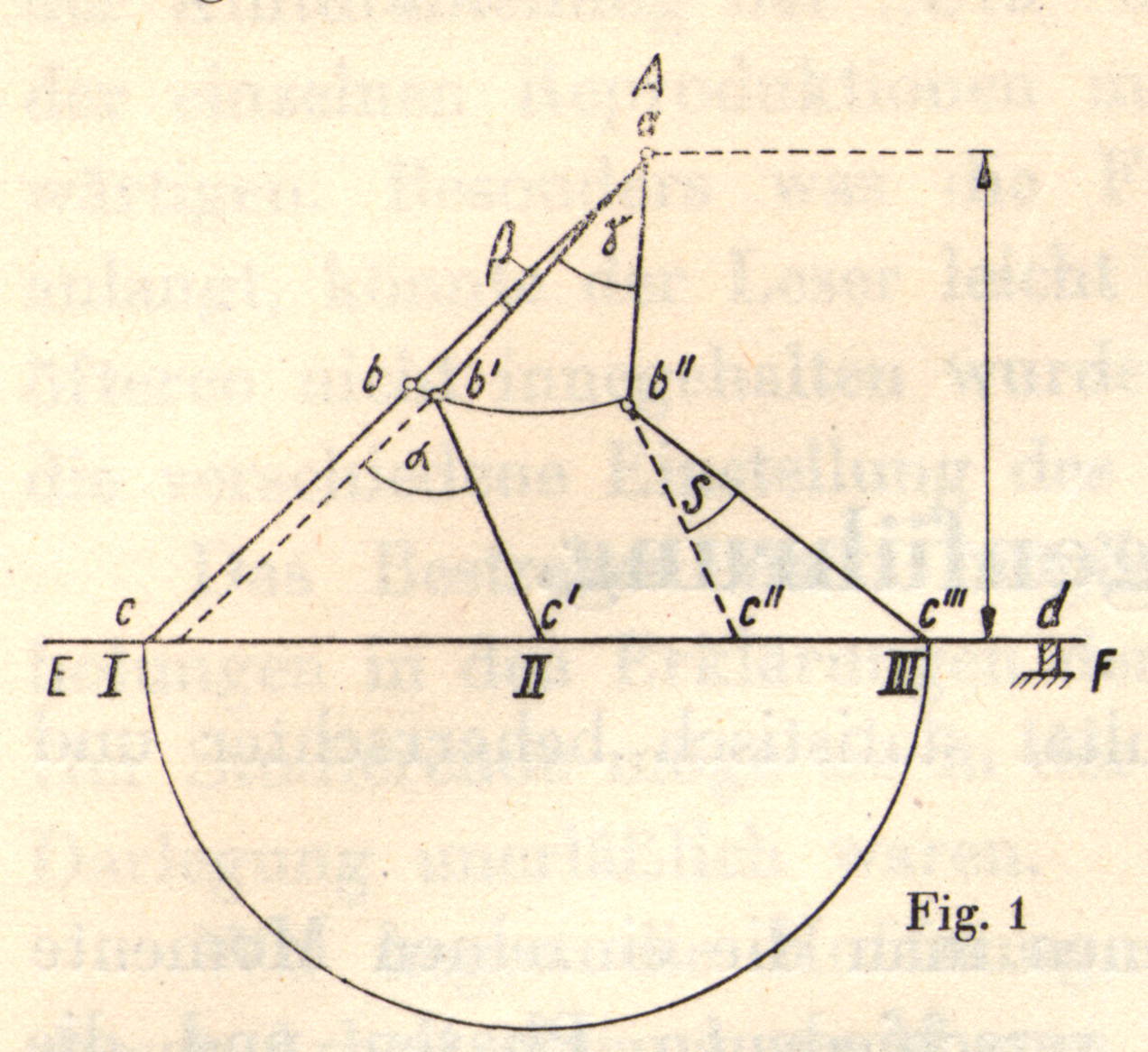

If we imagine the movements projected onto a plane parallel to the ground, the following schematic picture emerges when bowing on one of the middle strings:

Let A be the shoulder joint, b the elbow, c the hand at the bow. We distinguish three main movement phases. Phase I shows the bow at the tip; the forearm bc stands approximately in straight continuation of the upper arm (with a long arm at an obtuse angle), in the course of the upbow Phase II results. Here the bow touches the string with its middle. The upper arm has been adducted by the small amount of angle β (adduct = move toward the body). The forearm, however, has rotated in the elbow joint by the amount of angle α. Since the tip must also move outward, it must inevitably change the position of the forearm relative to the upper arm when retracing the path from tip to middle, in other words, a shortening of the lever system formed by the upper arm occurs during the up-bow in the upper third (conversely, an extension during the down-bow).

During completion of the up-bow, the following occurs: The upper arm is adducted further toward the body by the amount of angle γ, thereby the hand and with it the bow move forward to c” and finally the hand reaches the final Phase III through further angling of the forearm (angle δ). Whether the upper arm stops its adduction movement from a certain point and the forearm alone continues the bow, or whether upper and forearm remain coordinated in movement until the end, is initially irrelevant for our consideration. One can see from the sketch that the arm lever system abc has become relatively longer again when approaching the frog.

The reader should not be confused by the fact that the upper arm and forearm—which are constant—appear as different lengths in the diagram (ab, bc, ab’, b’c’, ab”, b”c”, b”’, c”’). This happens because we are looking at a flat projection of arm movements that actually occur in three-dimensional space, not just in one plane. As we will explain in more detail in the chapter on the full bow stroke, the elbow rotates somewhat backward during bowing, and the hand and fingers also bend and stretch. Because of these three-dimensional movements, the lines representing the forearm and bow (bc, b’c’, b”c’, b”’c”’) sometimes look longer or shorter in our flat diagram than they actually are.

The distance between the bow hand and the pivot point of the shoulder joint (which we can think of as staying in a fixed position) constantly changes throughout every bowstroke. The division of the arm into upper arm and forearm, as well as the flexion of the wrist joint, enable the arm to adapt to any distance between shoulder and bow. Likewise, the aforementioned “backward guiding” of the elbow contributes to regulating the peripheral movement of the bow hand; for every deflection of the elbow backward causes a shortening of the straight distance between shoulder and bow hand, provided the latter remains at the same level.

While the upper arm and forearm have to carry out the bow’s forward movement in the actual bowing direction, the hand and fingers are responsible for maintaining the straight line in the bow’s trajectory. This activity is called “compensatory movement” and describes both wrist compensation and finger compensation, depending on whether the wrist joint or the fingers are more involved in this process.

From a purely static viewpoint, one can easily imagine that compensatory movement at the frog, for example, can be done in two different ways, namely through pronounced bending of the wrist joint or through stretching the fingers.

But when it comes to actually playing the cello, it’s not just about static positions—the dynamic aspects of movement and technique are what really matter. In later chapters, we will explain how all these mechanical adjustments work as ways of adapting our natural body mechanics to the specific requirements and limitations of the cello.

Let us first give a brief overview of the physiological possibilities of our body’s moving parts: Every person can actively lift their upper arm (away from the body) and lower it, and also move it forward, backward, and to the side. Raising with an upright posture is called abduction, lowering is called adduction. Although more precise knowledge of the muscles brings no further advantages to the player, we mention (as an interesting fact) that the well-known deltoid muscle can only lift the arm up to a horizontal line. Raising it further to a vertical line necessitates a change in the position of the shoulder blade. The upper arm can also rotate along its length. If you bend your forearm at a right angle and keep your elbow in place, your hand will trace out part of a circle when you rotate your upper arm. The forearm acts as the radius of that circle.

The elbow joint primarily permits bending and stretching of the forearm. This means that humans are capable of lengthwise rotation of their forearm, in which the bone of the forearm (radius) crosses over the other (ulna). We call this forearm rotation. This is one of the most frequent and everyday movements. Every rotation of the hand illustrates forearm rotation. When locking a door to the right, the hand goes from a state of pronation to one of supination, and when opening it, the reverse is true.[4]

The wrist joint is capable of flexion and extension (bending and stretching), as well as sideways movement. A combination of wrist rotation and forearm rotation make circular motion possible for the entire hand. The thumb’s range of movement is very diverse. It can be placed opposite the palm (opposition), and also can be moved away from and toward the palm. Additionally, there are the stretching and bending movements of both phalanges (i.e. the individual finger joints). The four remaining fingers are connected to the palm at the so-called base knuckle joint. The flexibility of this joint brings with it the ability to spread the fingers in an extended condition: the more you bend the finger at the base joint, the less you can spread the fingers, and with extreme bending the ability to spread is practically zero. The remaining finger joints, like the joints of the thumb’s phalanges, are pure “hinge joints” that only allow movement in one plane.

The muscles that support and move the upper arm make up the shoulder girdle. Raising the arm (i.e. above the horizontal plane) is accomplished by changing the position of the shoulder blade. The muscles that bend and straighten the elbow are attached to the upper arm or shoulder girdle (mainly the biceps and triceps). The upper arm musculature can perform its function through leverage and rotational action.[5] The muscles that bend the wrist and move the thumb and fingers are located in the forearm. However, there are also some quite short muscles that have their origin at the base knuckle joint of the middle finger in the thumb, as well as on the individual phalanges: the interosseous and lumbrical muscles, as well as some short muscles for the movement of the thumb and fifth finger (abductor digiti V. et extensor digiti V. propr.). They support the action of the long finger flexors and extensors that originate from the forearm. They are very important because they bring about an increase in the performance of our hand. (Steinhausen underestimated their significance.) Furthermore, they enable certain movements, such as the spreading of fingers at the base joint, as well as the bending of the base finger joints with extended end phalanges.

The complex interplay of movements—triggered by muscles working together in the right combination and sequence under nervous system control—is called coordination. Only a healthy nervous system can ensure that movements happen in the proper order. We will explore the details of this in the following chapters.

We will later prove why it is necessary to have a flexible bow grip. Here, we will discuss its possibility.

Through the opposition of the thumb, as well as the functions of the four individual joints of the fingers, we have almost unlimited mobility of the hand. Let us now test the limits of hand movement by holding the forearm still and holding the bow.

First, we can move the bow upward and downward by stretching and bending the hand. However, this bending and stretching movement is not practical for actual playing. As you can see by comparing Figures 2 and 3, when the hand bends, the fingers get squeezed together so much that the entire hand ends up in a completely different position. If we tried to use this mechanism in actual playing, we would run into serious problems when moving from lower strings to higher ones. The bow would inevitably tilt every time we changed strings, which would make the volume fluctuate.

To solve this problem, we need to use what is called “longitudinal rolling of the bow.” Instead of gripping the bow tightly, you hold it loosely and make small twisting motions with your thumb and fingers against the bow stick. The thumb does most of the work—when it rolls up on the wood of the bow, it turns the bow hair downward, and when it rolls down, it turns the hair upward. The fingers can also help with this rolling motion; often the thumb and fingers work together.

By combining wrist and finger movements with this bow rolling technique, we can adjust to the different string levels without moving the forearm and without tilting the bow. Compare Figure 4 with Figure 2 to see the difference.

There is another important finger movement for playing called “double-lever finger action.” Using the thumb as a pivot point, the index finger and little finger work together to move the bow stick in what we call the “bow rotation plane.” (The ring finger can sometimes substitute for the little finger.) Th double-lever technique is especially useful when moving from one string to an adjacent one, particularly for playing near the frog.

This type of finger leverage should be clearly distinguished from another way of moving the bow, where the bow is held firmly between thumb and fingers and moved by forearm rotation so that sometimes the tip points up and the frog points down, and sometimes the frog points up and the tip points down. Double-lever finger action is the more flexible type of movement; it also combines better with wrist flexion and extension. Of course, forearm rotation is sometimes part of the technique too; it is used mainly for string crossings near the frog, especially when combined with broad bow strokes. We will explore the details of this mechanism when we look at specific bow techniques.

Now let’s explain the concept of the “playing axis.” Since we perform so many different rotational movements with our hand on the bow and with the bow itself, we need to address the question of which axis these rotations take place around. When the bow rotates lengthwise, it’s clear that the rotation axis is the bow stick itself. In the finger lever technique, it is the imaginary connecting line between the thumb and the contact points of the opposing middle finger, which can be considered the axis. This is generally what we mean by the term playing axis. However, we must also remember that the bow is not only rotated but also held. Finger friction plays an important role in this. It means that in reality the playing axis does not have the great significance that theoretical considerations might suggest. Moreover, the position of the playing axis changes continuously with the rotational movement, even if only by small amounts.

In cello playing, the dynamic principle of bow technique matters more than it does in violin, because the cellist has to apply greater forces.

The problem of achieving fluent bow technique is theoretically inconceivable without understanding the concept of force application.

Force application is the crucial point for understanding bow technique in general. While left-hand technique is made up of relatively few building blocks and presents no difficulties for understanding once the basic principles are clear, bow technique has always been perceived as something special. There have been varying approaches in the attempt to understand this extraordinary problem, and ever new secrets seemed to emerge before we could even analyze them. The fundamental principle of string instrument playing has been correctly recognized (see Capet):[6] force and softness, calm and lively movement, joy and pain, jubilation and lament, longing and renunciation—in short, all the emotions that humans are capable of feeling can be conveyed through the bow. This miracle of constant transformation of purely physical impulses through motor energy into acoustic effects by means of mechanical tools (though admittedly an example of perfect tools) can therefore be explained through rational analysis! We are going to focus on the most important aspect of this chain of events, though it is not necessarily the first step in the process. (The very first would be how a musical idea in the mind can be converted into physical impulses to create movement, but this is a philosophical question that touches on life’s deepest mysteries.)

In terms of the dynamic principle, we must ask the physiological question: how can we use natural forces in the service of optimal tone production?

The importance of this question becomes clear from the fact that the constantly incorrect application of force, usually in the form of unnecessarily excessive effort, not only hinders the technical development of aspiring musicians, but also leads to physical harm. Waltershausen[7] has already described shoulder tension and pain as an impediment to playing.

However, pain in part of a limb is already a consequence of incorrect movement patterns, since proper practice should not lead to pain. Pain occurs due to inadequate relaxation and incorrectly prolonged tension in one or another moving part, but not in participating muscles working in static function. We must distinguish between these two conditions. A muscle can be trained to relax through the conscious cultivation of a process of relaxation; this occurs automatically in a well-developed individual when tension is no longer necessary, and when one checks oneself deliberately. Detecting the accompanying movements or tensions is more difficult. Everyone can picture a beginner, whose tension is visible even in their facial muscles. However, it is often difficult to detect unnecessary tension in distant muscle groups during individual movements of the bow.

For this reason, I have used two objective measures for detecting muscular co-contractions. The first experimental arrangement consisted of a mechanical device being strapped to the muscle examined, which registered every increase in volume of the muscle (i.e. as an indication of tension).

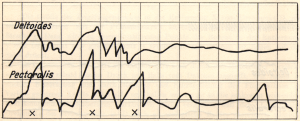

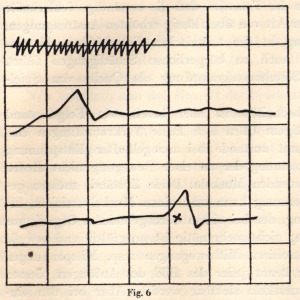

A series of simple bow strokes executed with excessive tension in the shoulder, as shown in the adjacent curve I (Fig. 5):

Both the deltoid and pectoralis muscles show signs of increased activity. The peaks of the curves indicate a state of increased tension (through increased muscle volume). The later the elevations occur, the more suddenly the tension appears. The points marked with an x correspond to the phases of the bow change. Here, the action is particularly intensified.

With a relaxed shoulder, curve II (Fig. 6) takes a much simpler course. This movement diagram corresponds to the so-called “forearm force application” that will be discussed later.

The muscles in question (deltoid and pectoralis) are not tensed in an unproductive, excessive way as in the first case. (The function of the deltoid muscle is to lift the arm; that of the pectoralis is to pull it down—the adduction of the upper arm.)

What’s interesting when comparing the two curves is that in the second case, the bow change can only be detected at one point (at the tip). The tension is distributed evenly throughout the entire bow movement.

A second, much more refined method for determining muscle action consists of measuring the electrical current that occurs with every muscle contraction, using precise electrophysical instruments. Anyone who is willing to have a few silver needles stuck into their flesh and muscles can replicate these experiments and verify them personally.

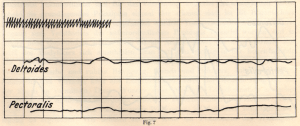

Here, too, the difference between correct and incorrect dynamic movement is demonstrated by objective evidence: curve III (Fig. 7) shows the activity of the pectoralis and latissimus dorsi muscles when playing with a properly controlled application of force.

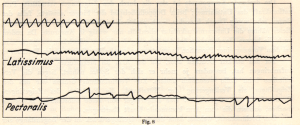

Next, curve IV (Fig. 8) demonstrates increased tension in the same muscles at exactly the same spot and with the same volume when using physiologically incorrect technique:

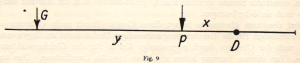

To properly interpret this experiment, we must refer once more to the pressure conditions on the bow. Volume, along with bow speed, is determined by the bow pressure exerted on the string. This pressure is delivered mainly by the pronation force of the forearm, which acts against the opposing thumb as a pivot point on the bow stick from above. A simple sketch may help to illustrate the “lever” action: (Fig. 9)

The amount of index finger pressure at distance x from pivot point D, which we consider identical to the pronation force, is represented by distance p. Then, at a specific point on the bow at distance y from the pivot point, a certain force G will result, with which the bow presses onto the string.

It’s clear that the index finger’s force can also be reinforced by the middle finger, as long as its pressure is only applied to the left of the thumb. In our analysis, we disregard all forces generated by friction and oblique positioning of the finger axes, and focus only on the vertically acting force components. We must not forget, however, that the physical pivot point of the lever system at D also absorbs physiological forces, namely those of thumb adduction and opposition.

A force that acts rotationally on a system is called a torque. It is equal to the product of the force multiplied by its perpendicular distance from the pivot point. In our simplified diagram, D would be the pivot point of the system, p the point where the force is applied. The finger pressure would then be determined by the product p × x.

The rotating component is therefore the pronation force of the forearm, transmitted through the index finger. When playing a double stop with the fingers, for example, very little torque is required if the bow needs little pressure. In this scenario, the forearm muscles are barely engaged. Since the short hand muscles also participate in bending the fingers, one hardly senses any muscular tension in the forearm during the act of pronation.

However, with strong arm pressure, as occurs in mezzo-forte and forte playing—especially as the bow approaches the tip, conditions are fundamentally different on the cello. To simplify the explanation of basic joint mechanics, let’s assume that the index finger’s function is switched off. The index finger should make no independent movement, but should transmit the force coming from the arm.

The torque that then comes into effect through finger pressure on the bow stick arises physiologically through a rotation of the forearm to the left (in the direction of pronation). Against the thumb, the forearm attempts to carry out its leftward rotation.

Now, equilibrium can only be maintained in any system on which rotational forces act when the arithmetic sum of all torques equals zero. For example, if a 3 kg force acts on a rotatable disk at a horizontal distance of 5 cm, then another force must act to keep the disk in balance. If this force acts at a distance of 3 cm, it must be 5 kg.

Applied to the arm, this principle means: for my forearm to generate the necessary torque on the bow for tone production through leftward rotation, the upper arm must ensure equilibrium by exerting opposing forces (a process of which we have no conscious awareness). This is achieved by the muscles at the shoulder joint, which act upon the upper arm to produce a rightward rotational tendency.

This interplay of forces requires a specific “average” arm position. We orient ourselves at the level of the elbow, because only with the movement of the arm (described in the chapter on full bow strokes) is it possible for the shortening and lengthening of the forearm required for string crossing to take place through simple bending and stretching at the elbow joint, while the rotation of the upper arm around its long axis happens automatically. The elbow moves approximately on a horizontal plane. If a player lifts their elbow high during down-bow strokes (especially a weaker player trying to generate more bow pressure), this upward arm movement automatically causes the upper arm to rotate inward. This inward rotation works against efficient force production, making it harder to generate the bow pressure you actually need.

Let us imagine that the balance of force at the elbow joint being switched on (for example, through stiffening of the joint or by encasing it in a plaster cast), so that the forearm and upper arm form a single rigid unit. In this locked-arm scenario, the only way to create the downward bow pressure you need is to rotate your entire arm leftward from the shoulder joint while simultaneously lifting your elbow up. This forces you to use your whole arm as one rigid unit instead of the more efficient segmented movement.

We must distinguish between these two types of peripheral pressure distribution, both conceptually and practically. Applied to the normal conditions of bowing, we have both possibilities: to distribute the pressure through rotating the forearm leftward, where the shoulder forces only have to keep the entire forearm in equilibrium; or to use the entire arm as a rigid lever, thereby applying force through an inward rotation of the upper arm via the shoulder girdle.

Actual rotations naturally do not need to occur, since all the strong pressures are still paralyzed by the elastic resistance of the strings. As soon as there’s enough give, the tendency toward rotation works against the string’s resistance. (If a disc remains at rest, even though a torque is acting upon it to set it in motion, then an opposing torque of equal magnitude acts on it, whether through axle friction or some other force that brings about equilibrium.)

The two types of physiological force application described above are not equivalent in terms of their mechanical efficiency. We must therefore ask which mode of movement engages the shoulder forces more, since it is clear that the one that burdens the shoulder muscles the least deserves preference. The pectoralis major and latissimus dorsi muscles have the task of adducting and abducting the arm with each bow stroke. If this is accompanied by a strong load from the torques that are necessary for pronation at the periphery to generate the bow pressure, the movement becomes impeded, especially when changing bow direction at the frog and the tip.

The inward rotation of the upper arm has the disadvantage that during the down-bow stroke, an actual elevation of the elbow occurs. As we will explain in more detail in the chapter on the full bow stroke, it is essential for unhindered bowing that the elbow remains at its level. We have therefore chosen not to speak of a “full bow stroke” in both directions (supination and pronation; see Steinhausen’s Physiology of Bowing), but rather to remain more or less in readiness for pronation. The reduction of force (for violin, this would be supination with the help of the little finger) is achieved on the cello through other measures (such as the “grip change.”) The cellist must avoid the inefficient technique of using the whole arm for support (which happens when the elbow is lifted too high). This problem inevitably occurs when we try to generate bow pressure by distributing the rotational force from the shoulder instead of using proper forearm rotation.

Can players actually become aware of these processes? Absolutely! These force theories were developed in harmony with practical playing experience.

A player who understands proper technique and practices correct movement patterns, or one who naturally integrates different technical elements into unified movement, will feel uninhibited and free while playing. They are free in a double sense: free from psychological inhibitions that create physical incapacity in others, and free from faulty coordination that can cause errors. This freedom in both physical and psychological realms creates the fortunate disposition which enables great achievements.

We can better understand the difficult and obscure area of movement technique by making important distinctions. First, we must separate “movement guidance” (the active motoric process of directing our actions) from “movement execution” (the passive following of the limbs, or “reactivity”). Second, we need to distinguish between the dynamics of movement (the form and quality of how we move) from the movement itself, even though both factors involve underlying muscular processes.

Since large-scale bowing is primarily a matter for the forces of the shoulder, the shoulders must not be unnecessarily burdened by using torques incorrectly to generate bow pressure. The shoulders should remain free from increased tension. Half of all playing problems, and the great majority of technical inhibitions, come from stiffening of the shoulder. This is caused by the too-rigid application of the shoulder girdle muscles as a result of incorrect bow pressure technique.

To make the matter easier to understand using key concepts, note that bow pressure comes primarily from the forearm (specifically from muscles that originate at the upper arm and attach to the forearm, enabling it to rotate along its length). Especially in forte playing, no tension should be felt in the shoulder and upper arm. Physiological training can help achieve this, as can attentive self-observation during practice, to reach the correct distribution between pressure application (forearm tension) and movement guidance (shoulder mobility).

How this theory works in actual playing will be shown in the following chapters.

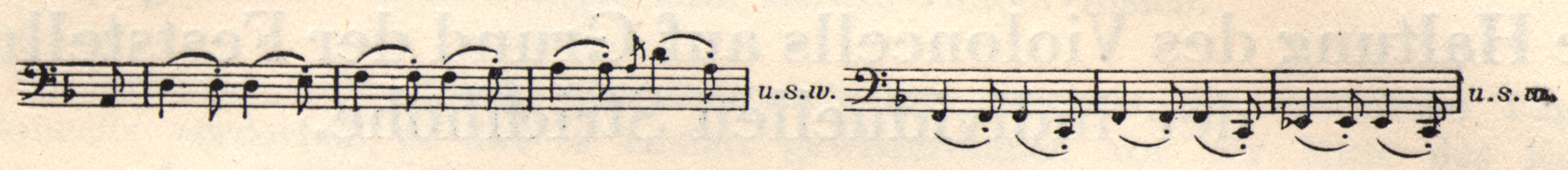

Abrupt bow changes provide an interesting example of the relationship between bow pressure and arm muscle dynamics. To avoid making extraneous scratching noises during “stopped” strokes, it’s essential to interrupt the arm movement precisely and reduce the pressure simultaneously. Full pressure must not remain on the bow while it is stopped on the string. Fixing the bow on the string after short, stopped movements can be achieved by just using forearm pronation for the distribution of pressure during the stroke. If the impulse engages the entire arm, the moving mass becomes too large to stop the bow in time—this might only be possible under abnormal arm tension (examples: two passages from Schubert’s String Quartet in D minor).

Based on these principles, we can now describe poor technique more precisely. An inexperienced player’s stiff playing style comes mainly from using arm forces incorrectly. Instead of the efficient forearm rotation system, they create bow pressure by using their entire arm with the shoulder as the pivot point.[8] This approach eliminates the elbow’s important role as a balance point for forces. Rather than using forearm pronation balanced by shoulder forces, the player twists the entire arm, which forces the upper arm to move towards and away from the body (abduction and adduction). This makes the subtle control of pressure forces at the bow-string contact point either impossible or achievable only through excessive strain.

But another factor makes this way of playing appear imperfect.

Pure, clean tone production depends not only on maintaining a straight bow trajectory and even contact between hair and string, but also on the consistent application of bow pressure. The most favorable condition for generating regular vibration in the string is naturally the perpendicular application of pressure from bow to string. Pressure is not applied directly at the point where the bow contacts the string (the sounding point), but rather at alternating forces applied at the frog end of the bow. The ideal condition for consistent perpendicular bow pressure is achieved when the partial forces of the forearm can engage at all points of the stroke through vertical-parallel movement. However, given the anatomical structure of our movement system, this cannot be achieved through torsion of the entire arm (with the elbow changing its level), but only through a controlled playing technique where the pressure is generated by so-called “forearm weighting,” while simultaneously relaxing the upper parts of the arm (including the shoulder).

- Arthur Jahn, Die Grundlagen der natürlichen Bogenführung auf der Violine (Breitkopf & Härtel, 1913). ↵

- Translator's note: Wilhelm Trendelenburg, Die natürlichen Grundlagen der Kunst des Streichinstrumentenspiels (Julius Springer, 1925). ↵

- Becker's note: "Jahn's book, in particular, provides the reader with a certain mathematical background with valuable insights into specific physical and physiological questions; much of it can also be applied to the cello with appropriate modification of the data. Studying Jahn's book is therefore highly recommended. Insofar as we may refer to the author's excellent research, we simplify our task by only discussing the specific cello aspects here.." ↵

- Becker's note: “Pronation refers to the position of the hand where the back of the hand faces downward; supination is where the palm faces upward.” ↵

- Becker's note: "The functions of individual muscles are not entirely clear-cut. For example, the bicep does not just pull the forearm toward the upper arm, it also rotates it into supination." ↵

- Lucien Capet (1873-1928), violin pedagogue and author of La Technique supérieure de l'archet (M. Senart, 1916). ↵

- Hermann Wolfgang von Waltershausen (1882-1954), a German composer, professor, and author. ↵

- Becker's note: "The player may and should occasionally use this method to achieve special sound effects, especially in cantilena passages." ↵