On the Physiology of the Left Hand

Forming a rational theory of movement for playing string instruments means understanding the movements and forces exerted by the left hand as well as the bow hand. For a flawless technique, which is the foundation for mastering demanding music, the right and left hands must coordinate perfectly. First and foremost, we must learn to synchronize movement impulses from both right and left sides. The success of performing difficult passages in détaché or off-the-string strokes depends on the finely tuned motor skills of both limbs. Furthermore, the force exerted by the bow arm must be independent of that exerted by the left arm. For example, when the bow approaches the tip and the right hand increases pressure on the string, this action must not be transferred to what the left hand is doing. By the same token, when the left-hand fingers increase their pressure in high positions on the fingerboard, which is essential for clear articulation, this should not cause an unintentional increase in bow pressure. (On the contrary, a reduction of the latter is usually appropriate.) This also involves discussing why so many string players perform multiple audible glissandi and place their portamenti incorrectly. This has less to do with musical interpretation than with an inability coordinate the application of pressure with the bow hand while keeping the left-hand movements independent. During glissando, bow pressure should be reduced. However, since the muscles of the left arm become more tense during the movement, especially in wide shifts, this is easily transferred to the bowing arm as a kind of reflexive tension. This tendency partly explains why it is so difficult to play a four-octave scale at a rapid tempo on one bow. When shifting from lower positions to the higher ones and vice versa, abrupt movements can occur in the muscles of the left arm. But the movement of the right arm must remain completely unaffected by this. Movement develops according to its own laws and is determined solely by the strength of the tone, which in turn is a function of speed and pressure (taking into consideration the tilt of the bow).

At this point, we must understand the deeper meaning of rhythm from a physiological perspective. It is incontrovertible that fast playing is a matter of motor dexterity, but it often manifests in a musically inadequate way: namely, unrhythmically (or, to be more precise, arhythmically!). During practice, tempo choices are typically determined by the level of bow dexterity, or the agility of the left hand. Rhythmic inconsistencies can easily arise because players often overlook that the bow arm and left hand rarely develop at exactly the same rate. Consequently, the motor function of one side or the other gets forced beyond its capabilities, and movement becomes unbalanced when its speed does not emerge organically from increasing skill (i.e. through refining coordination) but is instead forced through constrained muscular effort. Therefore, rhythm should not be solely the the property of just the bow arm or just the left hand, but must be anchored centrally in the musical consciousness. The degree of speed in practice should always be determined by carefully considering how far rhythmic coordination between the left and right sides has actually progressed. While endless repetitions can increase tempo to virtuosic levels, only control through musical awareness makes the performance artistically viable by ensuring that it is rhythmically flawless.

Principles of movement for the left hand are fundamentally determined by the spatial conditions of the cello. This will be discussed thoroughly in the sections on left-hand technique. Whether the hand should be positioned one way or another, whether fingers should be placed on the string steeply (on their tips) or on the flat pad of the distal joint—these decisions are primarily determined by the physical nature of the cello, though we must also consider the anatomical structure of the player’s limbs.

In the context of these physiological discussions, we should examine the dynamic element of the left hand and arm. Their application of force must follow the same strict requirements of physiological efficiency that apply to the bow arm. The principle of minimal force applies equally to our entire technique. When pressing down the strings with the fingertips or the side of the thumb, only as much force as necessary should be applied to the specific action. Stronger pressure is both physiologically inappropriate and pointless, the strength of the tone depends solely on the bow. This naturally doesn’t preclude using stronger pressures specifically for the gymnastic strengthening of the fingers.

In lower positions, the thumb serves not only as a guide for the hand, participating in every movement like the slider on a slide rule. It also saves energy by providing counter-pressure for the fingers. If you press the strings with your fingers while removing your thumb from the neck, no great force is required to determine the pitch. However, this distribution of force to the arm musculature is physiologically disadvantageous. The hand’s weight alone is not enough to exert the necessary pressure; instead, active contraction of the shoulder musculature in the upper arm (that is, lowering the arm) becomes necessary.

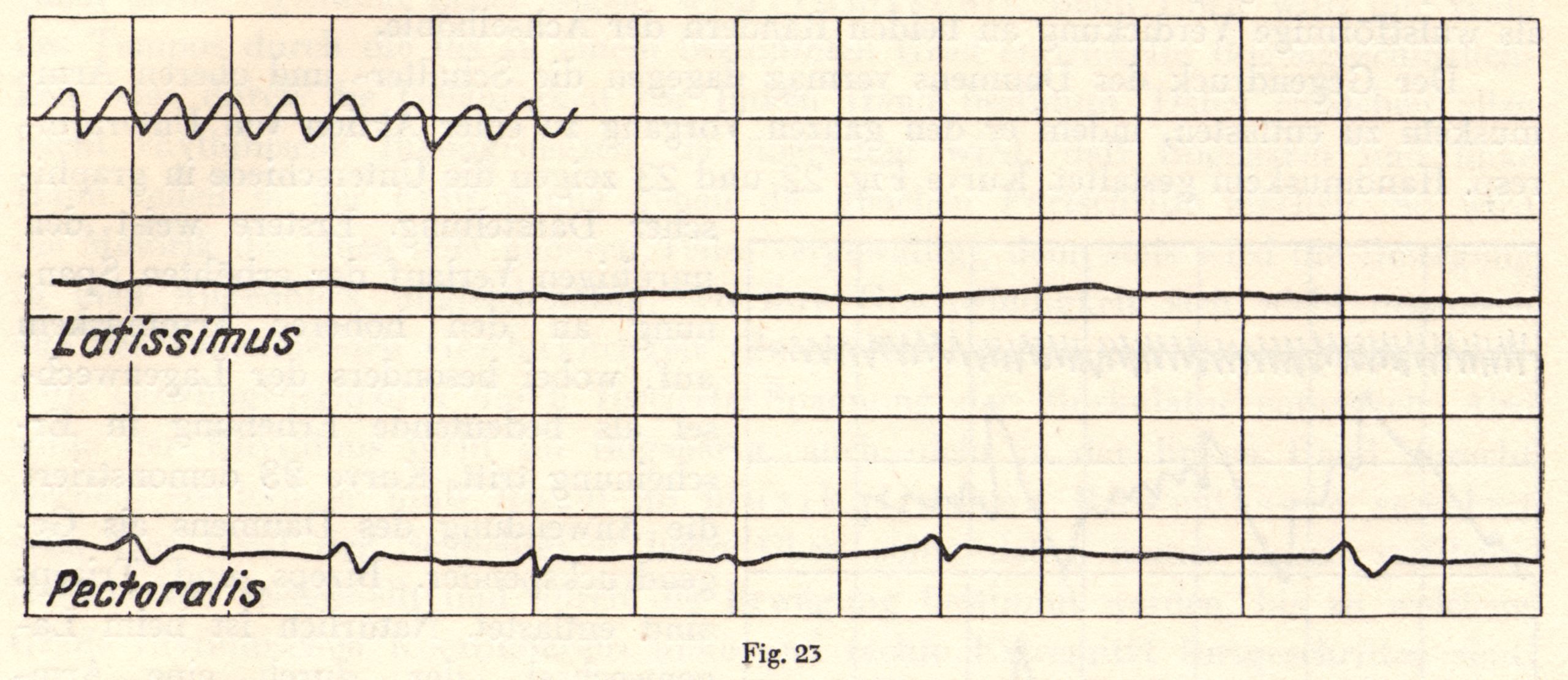

One can feel the tensed latissimus dorsi and pectoralis major muscles as cord-like “bulges” along both sides of the armpit.

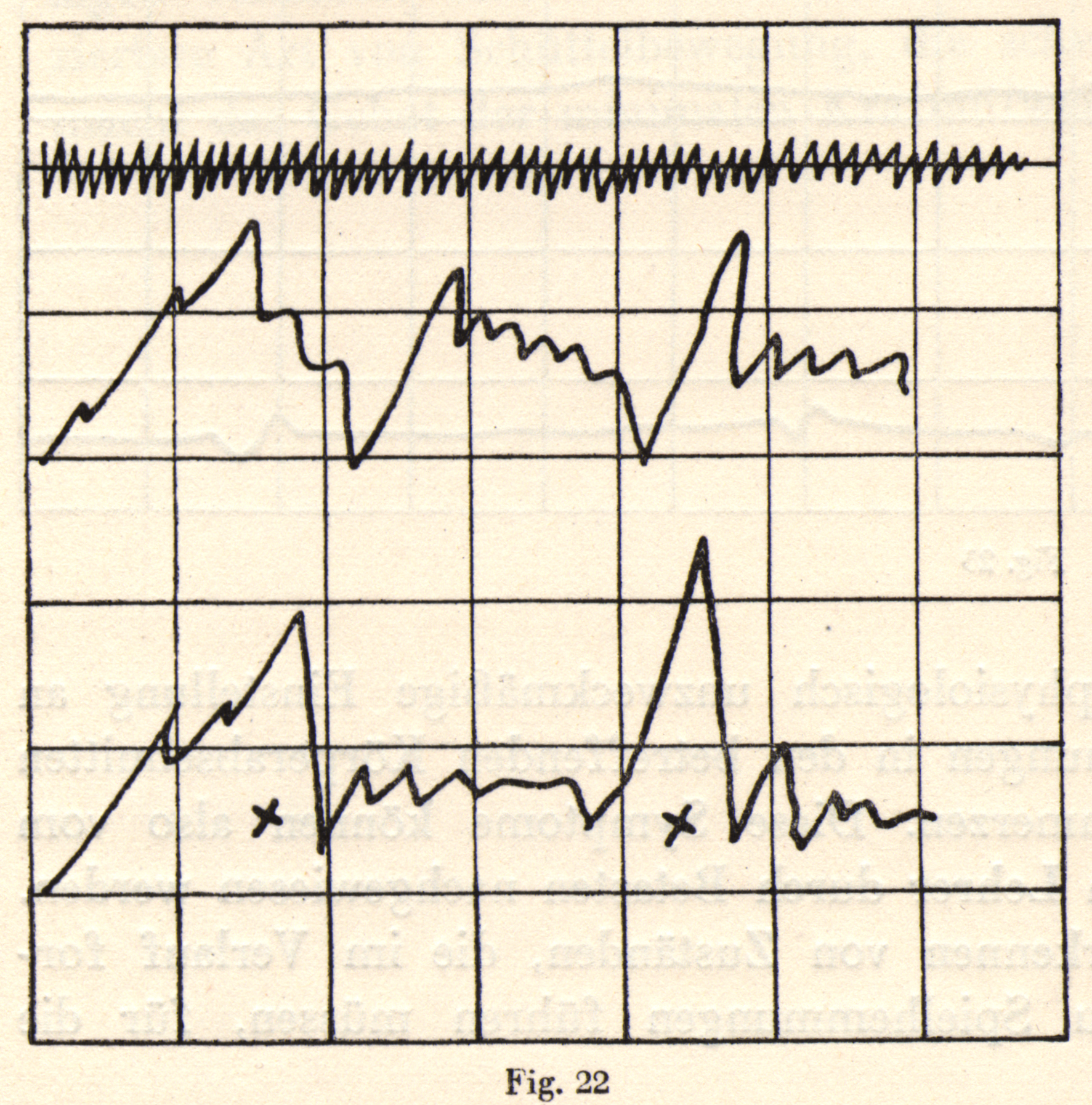

The thumb’s counter-pressure, however, can relieve the shoulder and upper arm muscles by transforming the entire process into an action of the forearm and hand muscles, respectively. Figures 22 and 23 show us a graphic representation of the differences. The former shows the uneven progression of increased tension in the upper arm muscles, with the change in position particularly noticeable as a significant elevation.

Figure 23 demonstrates the use of the thumb as a source of counterpressure. This relieves the biceps and triceps. Naturally, when shifting between positions (which occurs through arm extension or flexion), the activity of these muscles is necessary and cannot be eliminated. We distinguish between the activity of the forearm muscles in distributing pressure with the fingers and the activity of the shoulder or upper arm muscles during position shifts.

If we were to always play in the lower registers without the thumb on the neck of the cello, the tension in the shoulder muscles would increase excessively with each shift of the hand when changing positions, resulting over time in increasing shoulder tension. Indeed, this state of shoulder tension is the most common cause for a number of obstructions in playing. We could make an analogy here to the behavior of the right arm in bow technique. While the shoulder muscles are already heavily used in the simple application of pressure to the bow, the resulting bowing at forte dynamics results in such an increase in tension in the muscles of the shoulder and upper arm that it starts to obstruct playing. We thus notice a natural congruence between the left and right sides of our playing apparatus.

In the case of physiologically incorrect use of the distal parts of the body, tension in the higher muscular areas occurs; whereas the correct, appropriate application of force allows the arm to function as a flexible system, loosely suspended from the shoulder joint, and facilitates the greatest increase in mobility across all individual joints. Furthermore, one can see from these connections how wrong it is, when practicing, to focus one’s attention solely on isolated aspects of the movement sequence, and how much the hand technique also depends on the correct processes in the sections of the limbs closest to the body.

In practice, physiologically incorrect posture shows up in increased, objectively verifiable tension in the relevant body part—and in subjectively felt pain. The student may report these symptoms, which can also be detected by the teacher through touch. It should be noted that it is very important for the teacher to attend to such conditions in a timely manner, because they inevitably lead to playing problems during intensive daily practice.

The correct method of dynamizing our natural playing apparatus, explained above—where the distal body parts are primarily responsible for the transmission of force—has the further great advantage of allowing the small supporting hand muscles (lumbricals and interossei) to become well-developed. This makes the hand more powerful and expressive.

In the left hand, we particularly notice this advantage when playing in the higher registers, where the thumb, acting as a counterforce to the fingers, itself becomes a playing finger. If the muscles of the hand are weak and underdeveloped, we can incur the same symptoms as with increased shoulder tension in the lower positions. These are pain and muscle stiffness, which will be felt primarily along the back of the hand.

When the thumb is used as a playing finger, it adheres to the fingerboard as a “base” for the hand. If it is pressed firmly onto the strings, it facilitates playing for the other fingers in a similar way to playing in the lower positions: that is, through reduced arm tension.

In Popper’s Spinning Song,[1] for example, the fingers move more precisely and easily across the strings when the main pressure of the hand consistently rests on the thumb. This gives the hand greater stability and the fingers greater mobility.

Special attention should be paid to vibrato, which is so important for the left hand. In the lower positions, we primarily execute it through forearm rotation, with the hand acting as an oscillating mass; the physical weight of the arm plays a role. For hand to be able to oscillate unhindered—since this is the only way to execute a smooth, elegant vibrato at variable speeds—we must significantly reduce tension in the upper arm and shoulder. The principles are always the same! In thumb position, the more straightforward forearm rotation we would use for neck-position vibrato transforms into a more complicated type of oscillating motion that is difficult to describe. But even here, there are no exceptions to the principle of minimal expenditure of force.

- David Popper, Spinnlied from Concert Etudes, Op. 55. ↵