String Crossings

To perform a proper string crossing (that is, the connection of two notes on different strings), two requirements must be met. In musical terms, it demands homogeneity of sound and integrity of rhythm. The string crossing should not become audible through an unintentional accent on the second note, nor should the rhythmic structure of the sequence of notes be disturbed even slightly; the string crossing should not be acoustically perceptible. In mechanical terms, the technique for executing string crossings in all possible parts of the bow and for every type of connection between two notes (legato, staccato, détaché, or spiccato) must be determined and ingrained into our memory to make sure that the bow can move from one string to another in the simplest, easiest way while still maintaining a right angle to the strings and a consistent bow tilt, and minimizing any lifting and lowering movements of the arm. To achieve the latter, the arm should maintain a position from the start that allows it to control the playing plane of the adjacent strings.

Position of the Arm During String Crossings

There is a fairly common tendency among cellists, which is especially noticeable in piano passages, to use exaggerated arm movements when executing rapid passages spanning multiple strings. This is a result of an inability to perform string crossings without pronounced lifting and lowering movements of the arm.[1]

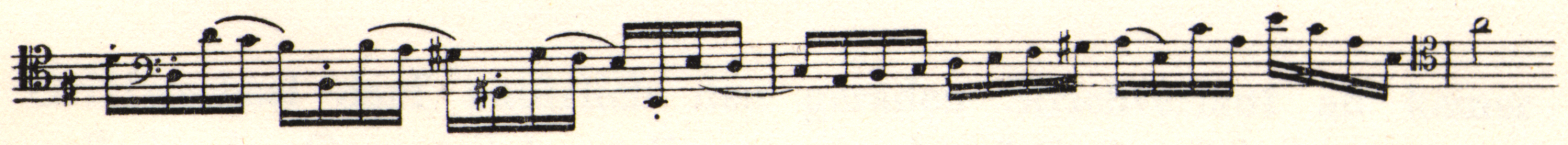

Passages such as those in the final movement of Schumann’s Concerto:[2]

or in the first movement of Romberg’s Concerto in E Minor:

or Hugo Becker’s Caprice in A minor:

will sound clumsy and awkward if the arm does most of the work.

To avoid this error, we should establish the following principle: when playing passages that span three strings, the arm should always assume the position corresponding to the middle string, and maintain this position for notes played on either adjacent string.[3] It follows that the transition from one string to another is accomplished through movements of the wrist and fingers. We can achieve balance between the fingers. We therefore have to distinguish between two main arm positions: that of the G-string for figures on the three lower strings and that of the D-string for figures on the three upper strings. Three additional arm positions are required for passages that only occur on two strings: C-G, G-D, and D-A.

Finally, in certain cases, e.g. when great force is required, a specific arm position may be used for each individual string. In a smoothly flowing cantilena, for example, where power and fullness are more important than lightness, the whole arm may accompany the hand as the bow crosses over the strings, although it is also important to avoid unnecessary raising and lowering movements of the arm. However, when playing figures more quickly, it is essential to go by the principle outlined above, i.e. to use the arm as little as possible for string crossings. Of course, the supination and pronation movements, which often involuntarily accompany the extension and flexion movements of the hand, remain unaffected. Also, lateral arm movement must not be affected in the slightest by these influences, since otherwise the tone production would suffer.

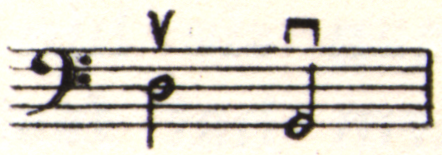

Performing string crossings means overcoming the difference in playing planes while simultaneously connecting to the new playing plane. Let’s first consider the simple process of connecting two whole-bow strokes on two different strings:

A) String Crossings at the Tip

1.

We perform the down-bow stroke on the D-string in the normal manner (i.e., higher wrist at the frog, lower wrist at the tip) to the tip (see image 14 of the Appendix). By bending the hand and extending the fingers, we reach the G-string (see image 15). During the subsequent up-bow stroke, the wrist remains raised to regain the movement at the frog to get to the D-string without using the arm. Images 16 and 17 illustrate the process of hand movement and finger extension.

If we repeat the process in the same way on the other strings, the mechanics of the string crossing are the same everywhere; the only difference is that when there is a different playing plane, the position of the arm changes. Depending on whether we are on the A-string or G-string, the forearm will be slightly more pronated or supinated.

From the above observations, we derive Rule I: that the down-bow on the higher string, followed by the up-bow on the lower string, is performed in the normal way. String crossing at the tip to an adjacent lower string should occur to hand flexion and finger extension (see images 16 and 17 of the Appendix).

2. In the case of a string crossing at the tip to the adjacent higher string, the situation changes.

If we performed the down-bow stroke in the normal way, allowing the wrist to sink towards the tip, we would be forced to make the transition to the next higher string with the whole arm, since the remaining stretching movement would no longer be sufficient. (We can see how small the range of wrist movement is before reaching full extension by comparing images 16 and 17.) For this reason, we keep the wrist elevated up to the moment of transition to the higher string. This measure, which deviates from the norm and leaves the hand on the bow in its original position, is called “reserving.” [4] This results in Rule II: if we want to go to the next-highest string at the tip at the end of a full bow stroke, we must “reserve” the wrist (see image 19).

The process of bending and stretching the hand is connected with the so-called “active longitudinal bow rotation,” which was discussed in the section on the physiology of bowing. This consists of a quarter-circle rotation of the hand around the bow-stick, and requires a loose bow hold. Its purpose is to prevent the bow from tilting, which is inevitable with a rigid grip.

B) String crossings at the frog

While string crossings at the tip necessitate a very long lever arm, string crossings at the frog require a much shorter lever. For this, the double-lever action of the fingers may be sufficient.

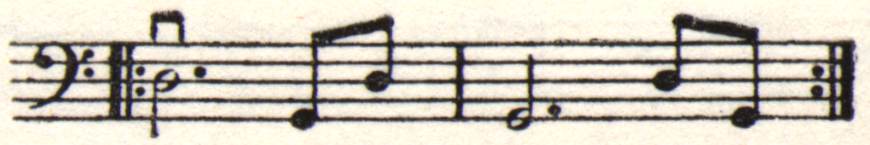

The normal up-bow stroke shown in this example is followed by a down-bow stroke that crosses to the G-string using this double-lever action. Consequently, we would have to “reserve” the high wrist position for the down-bow stroke and the low hand position for the up-bow stroke. However, since the lever length of the bow is greatly shortened by approaching the frog, we can help ourselves in another way, namely by using double-lever action[5] of the fingers:

(From Friedrich Grützmacher’s Technologie des Violoncellspiels, Etude No. 7.)

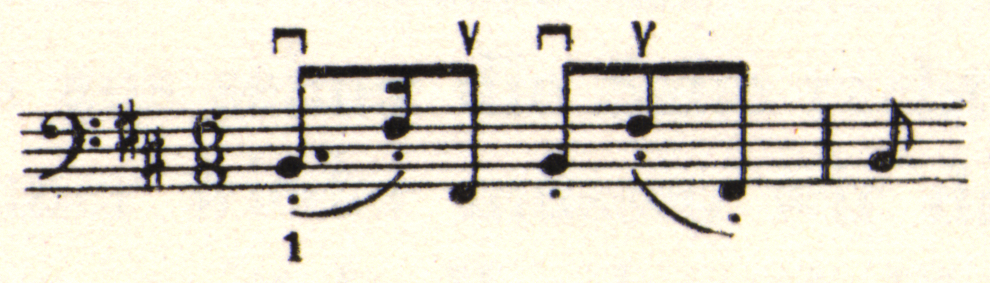

When playing the following figure:

the steps for correct string crossing arise naturally as a result of the normal bow stroke.

However, if we begin the same exercise on an up-bow, difficulties arise with the string crossing: we reach the higher string with a high wrist and consequently cannot reach the lower string without using our arm. To counteract this disadvantage for bow control, we must “reserve” the wrist for both the up-bow and the down-bow.

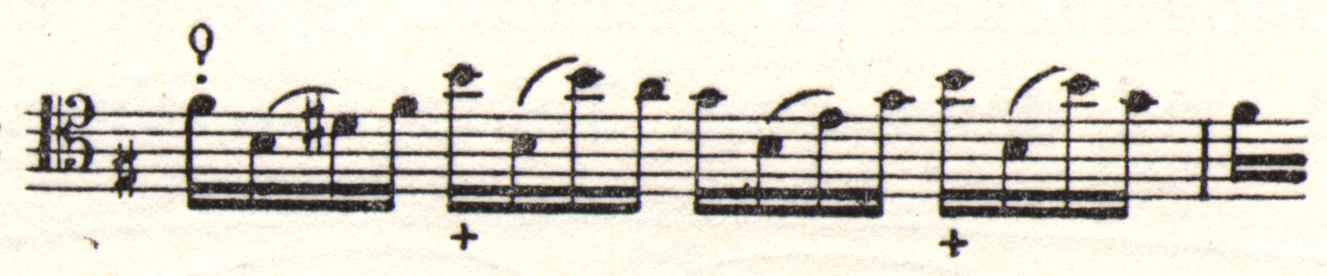

C) String crossing in the middle of the bow

If we play the same exercise in the middle of the bow, we recognize that the mechanics of “reserving” are equally important towards both the frog and the tip.

In the following example:

it is necessary to reserve the up-bow on the high B marked with +, otherwise we would be forced to make an arm movement when crossing to the D-string, which would give the passage a certain heaviness.

The wrist should be neither high nor low, but at a medium level, allowing the hand to guide the bow equally easily to both the higher and the lower strings. This principle mainly applies to playing in the middle and lower thirds of the bow. For the upper third, we need slight support from the arm; that is, the forearm makes a small horizontal movement from backward to forward.

To an even greater extent, the arm participates in this movement when crossing over four strings, especially in arpeggios with full bow strokes (e.g., at the beginning of the d’Albert Concerto). The movements of the arm involve less lifting and lowering (as on a pump lever) than moving slightly back and forth in a horizontal way. Naturally, these arm movements must be accompanied by compensatory movements of the hand and fingers.

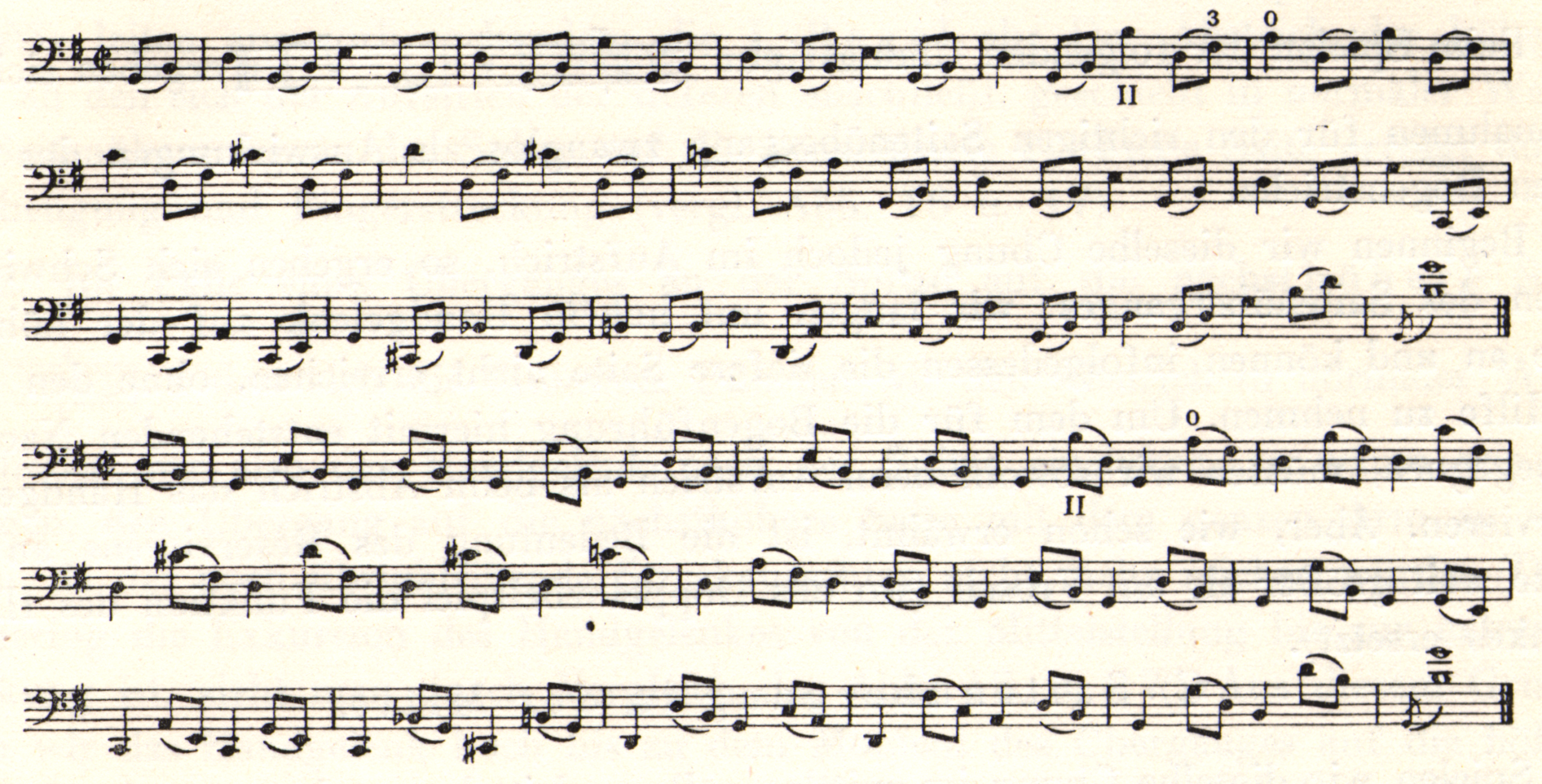

To ensure secure string crossings in combination with all conceivable bowing patterns, practice the following example in the three sections of the bow with alternating up-bow and down-bow strokes.

Regulation: as soon as a bowstroke is performed across more than two strings, the only way to avoid unnecessary arm movement is to adjust the wrist. For example, if we play the C major scale, first with one measure to a bow and then two measures to a bow:

we reach the G-string for the first time by “reserving” the wrist. The hand thus comes to rest on the G string in an outstretched position. If we were to leave the wrist at this level while continuing to play, we would only be able to reach the next higher string using the arm. To counteract the disadvantage this creates for bowing, we must create a state that allows us to reach the next higher string using the wrist again. We raise the wrist by moving the hand and bow upward in a quarter-circle motion (so that the wrist is elevated and capable of reaching the D string by extending). We can repeat the same process to cross to the to the A-string, so that within the above scale, the wrist is lowered once and adjusted (raised) twice. When descending the scale on an up-bow, the hand is already in its normal position (lowered wrist), making it easy to reach the D-string.

But then the need for regulation begins again. If we begin the scale on an upbow, the wrist must be raised a priori in order to reach the G-string by extending the hand. This is where the adjustment begins. We reach the A-string with the hand outstretched (i.e. with a lowered wrist). When descending, we keep this configuration unchanged. Adjustment then takes place as described above.

To achieve a smooth, fluid execution, it is necessary that regulation and horizontal arm movement do not occur simultaneously, but one after the other, because regulation represents a local measure of the hand, but the adjustment of the arm to the respective playing plane is done with an impulse of the arm. This time difference, which is difficult to see during rapid execution, can be clearly seen in a slow-motion film recording.

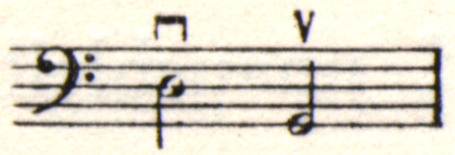

A short exercise to demonstrate this adjustment is as follows:

Practice this in up- and down-bows in the middle, at the tip, and at the frog.

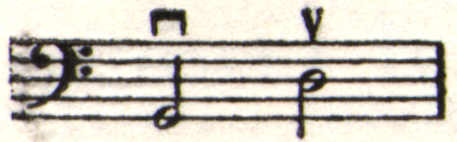

Then practice the following exercise in reserving and regulating:

The fifth measure of Bach’s G major Prelude clearly shows us the necessity of both reserving and regulating:

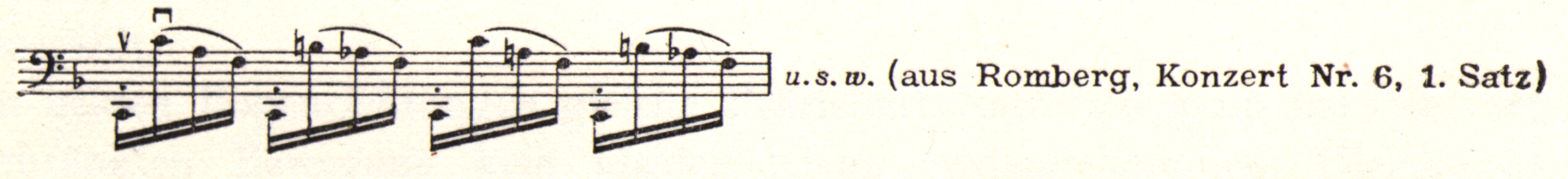

String crossings that skip over the middle strings require an intensive change of bow-hand position. In the following passage from the first movement of Romberg’s Concerto No. 6, aside from the change in playing level, we must also pronate the forearm and make a “double lever movement” of the fingers (in the air) to bring about the string crossing.

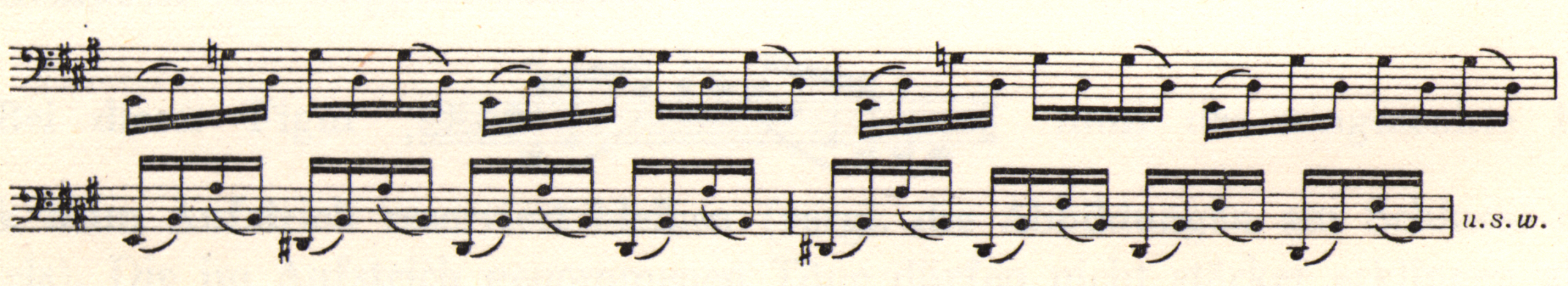

An example of crossing over three strings (from the first movement of Beethoven’s A major Sonata):

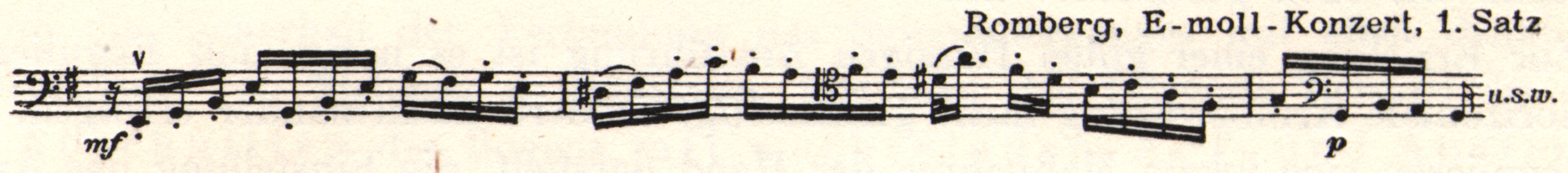

Further examples of characteristic string crossings, mainly executed by the hand and fingers (Romberg, E minor Concerto, first movement):

or from the present author’s Special Études, No. 2:[6]

Images 20, 21, 22, 23, and 24 of the Appendix show, in order: starting position on the D-string, up-bow on the C-string near the frog, down-bow on the G-string, up-bow on the D-string near the frog, and subsequent down-bow on the A-string.

- Becker's note: "Duport already made this demand. In his Essai sur le doigté du violoncelle, et sur la conduite de l'archet (published around 1770),* he writes in Article 4: 'The second movement of the wrist serves to move from one string to the other. If, for example, the bow is on the D-string, one may only raise the hand slightly to bring it to the A-string; if, on the other hand, one had lowered it, it would have landed on the G-string; the arm has almost nothing to do.'" *Becker is mistaken: Duport's book was actually published in 1806. ↵

- Becker's note: "From Frau Clara Schumann I learned that Robert Schumann actually intended the forte in the cello part to occur only at the third occurrence of the above motive (the beginning of the theme), whereas before that it should appear somewhat timidly." ↵

- Becker's note: "When practicing, particular attention must be paid to the adjustment of the arm. Only when the player is convinced that they are capable of moving the bow from one of the middle strings to the adjacent higher or lower string without having to change the position of the arm may practice begin." ↵

- Becker's note: "A term introduced by [Becker's teacher] Friedrich Grützmacher, Sr. 'Reserving,' whether in the upstroke or downstroke, means that we keep the hand in its starting position." ↵

- Becker's note: See Steinhausen, Physiology of Bowing, page 64, Figure 12. ↵

- Translator's note: Sechs Spezial-Etüden zur Erwerbung größerer Leichtigkeit im Bewegungssystem des Violoncellisten, Op. 13. Leipzig: Hansen, 1920. ↵