The Détaché Stroke

Just as it is on the violin, the détaché stroke is one of the most important bowing techniques for the cello. There are some ambiguities regarding its terminology. According to common nomenclature, this term is used for bow strokes executed with varying speeds and any length of bow, usually playing one note per stroke. An essential characteristic is the absence of pauses between strokes. Even full-length bow strokes can take on the character of détaché, making the performance extraordinarily grand and energetic—for example, at the beginning of the first measure of the Prelude from Bach’s Suite in C major.

A détaché, which can sound good anywhere on the bow, is versatile precisely because (unlike off-the string strokes) it is not tied to a specific part of the bow. Besides mistakes such as a slanted bow,[1] poor string crossings and bow changes, an inadequate détaché is to blame for various unpleasant inadvertent noises (which have earned cellists that well-known, malicious, but unfortunately often justified alliterative joke about the “screeching cello”).[2]

Let us first consider the physiological necessities, distinguishing between the détaché below the midpoint of the bow, détaché above the midpoint of the bow, and détaché in the middle of the bow.

Détaché movement in the lower third

First, let us examine the possibilities of executing shorter strokes near the frog (Fig. 15):

a) By rotating at the elbow joint (with a stiff wrist), it is certainly not possible to have back-and-forth movement, because the bow would deviate “upwards” on the A-string. (E H and E H’ represent the two forearm bones—the radius and the ulna—which form the sides of an isosceles triangle in this diagram.) Therefore, we must compensate through extreme flexion of the wrist on the up-bow stroke and a corresponding lowering of the wrist on the down-bow stroke. However, the frequent repetition of this process requires continuous, vigorous wrist movement, which would inevitably destroy a pleasant tone. Moreover, the unavoidable tilting of the bow stick, where the tip of the bow would point downwards on the up-bow stroke and upwards on the down-bow, proves how unidiomatic such bowing motions are for the cello.

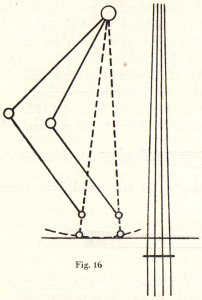

b) The larger the radius of a circular motion, the more a small segment of the arc almost looks like a straight line. So to create a “straight” bow movement, we need to make our arm into a very long “lever.” In other words, we will use the shoulder as a pivot point, and the upper arm and forearm as a “fixed lever” (as if there were no elbow joint in between them). (See Fig. 16.) Of course, this does not mean that the arm has to be tense. On the contrary, with the slight pressure on the bow stick near the frog, the whole arm can be considered as an absolutely relaxed system that can rotate from the shoulder. Through this movement from the shoulder joint, we are able to move the bow back and forth at a right angle to the string near the frog, even with a rigid wrist and motionless fingers. Of course, rotation in the shoulder joint occurs in different directions depending on the playing plane. On the A-string, the upper arm moves diagonally outwards and upwards; on the D-string, it moves almost horizontally, and on the C-string it moves more backwards and downwards. (These instructions refer only to the guidance of the movement, not to its dynamics.)

However, with very rapid sequences of strokes, we will feel a certain stiffness and heaviness in the movement. This indicates that we should not let hand and finger move like a dead weight, but should absorb the arm’s momentum through finger activity, transferring it to the bow. (Flexibility through springing finger movement, essentially a reduced grip change.) The wrist movement is so minimal that we can disregard it. Practically speaking, the movement occurs in the shoulder and fingers.

Through this combination of shoulder and finger movement, we achieve optimal playing conditions for détaché near the frog. The cello can make a full tone that is free of superfluous noise, even when moving the bow fast.

From this we can derive the following rule: never perform short strokes in the lower third of the bow with the hand alone, but always in combination with the upper arm. For strokes that use larger sections of the bow, up until approximately the middle of the bow, we will use the full pronounced change of bow grip on the frog, just as we do for full bowstrokes.

We will now learn

Détaché in the upper third of the bow

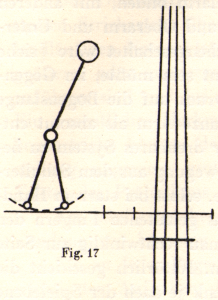

Here, we can make use of the movement of the forearm with the elbow as the pivot point. As Fig. 17 shows, the forearm forms the apex of an isosceles triangle when executing up- and down-bow strokes. (Upper arm movement remains minimal.)

For broader bow strokes, execution using only the forearm is quite possible, especially when playing forte and at a moderate tempo. However, the more we use the tip of the bow for détaché, and the faster we play, the more we use lateral movement of the wrist and replace forearm movement with finger action. During string crossings, we should also consider adjusting how we use our fingers.

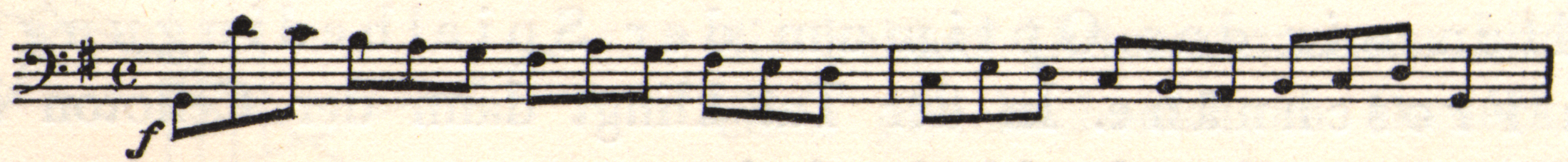

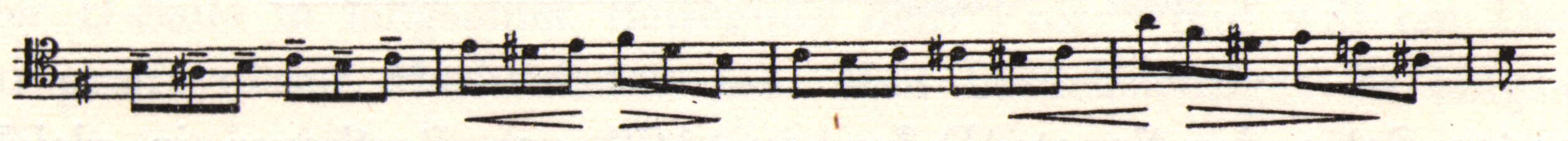

For example, let us play the following passage using détaché in the upper third of the bow at M.M. ♩ = 80, using plenty of bow (approximately as shown in Fig. 18), and considerable forearm movement.

![]()

When playing F on the C-string, prepare for the upcoming string crossing to the G-string. “Refill the reservoir,” i.e. regulate, when playing C on the G-string, so that the string crossing to the D-string can occur without arm movement! (Image 52 of the Appendix demonstrates the moment of crossing onto the A-string.)

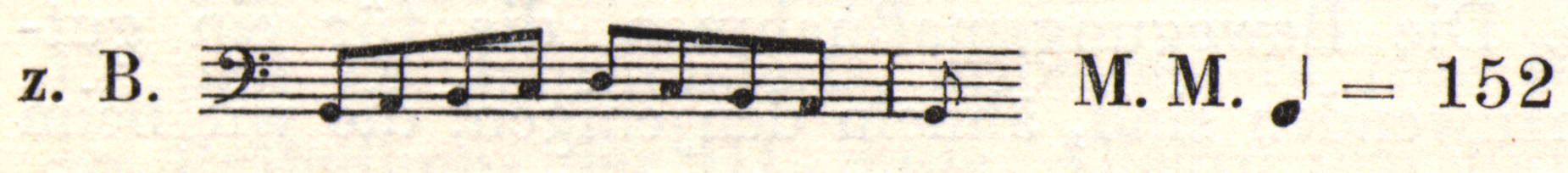

If we play the same passage at double the speed, i.e., M.M. ♩ = 160, we can largely eliminate the forearm movement, restrict the range of motion, and replace it with lateral movement of the hand and fingers. The following passage (by Berteau, from Duport’s 21 Etudes[3]) should be played in a similar way:

Now, a few more points on the dynamism[4] of détaché at the tip: just as the faulty combination of two main factors of movement (the arm and the fingers) disrupts bowing technique, the incorrect dynamization of the muscular playing apparatus is also disruptive. In the section on the physiology of bowing, we learned how acoustically perceptible sound effects are produced by analogous physiological processes in the muscles that generate a unified sequence of movements.

Every tense beginner realizes that the uncontrolled application of force not only fails to increase the tone, but also muddies the sound with extraneous noises. It is not excessive, uncontrolled force, but the finely balanced interplay of forces that enables advanced technical skill. However, for these forces to work effectively, they must be applied independently and in varying ways. Even the simple up-bow and down-bow stroke require this: pronating pressure toward the tip, and the relief of pressure toward the frog and the grip change.

As we approach the frog (as we have already learned), the grip change is a valuable substitute for a supination of the hand. The grip change is a more consistent way to bow here than a supination, since the latter is difficult to perform, especially when playing fast (as Steinhausen has established).

Dynamics require special consideration in the upper third of the bow. Here, a détaché in forte and mezzo forte can only be executed by applying quite strong pressure to the bow stick, which remains on the string for the entire duration of the horizontal back-and-forth movement.

Two challenges, (a) maintaining a consistent pressure so that up-bows and down-bows are equally strong and (b) keeping the right angle between bow and string, can only be overcome by resting the entire weight of the arm on the bow stick and utilizing the shoulder forces (latissimus and pectoralis muscles) to increase the pressure. However, the fingers and hand ensure consistently horizontal movement. (The movement is only horizontal on the D-string; on the other strings, its direction can deviate from the horizontal depending on the playing plane!)

Let us say more about the performance of the right hand when executing détaché at the tip. It is more difficult to create a consistent tone when bowing at the tip, since it not only requires that we transfer the arm’s full pressure to the bow, but that the bow’s trajectory remains absolutely straight. Playing ability is reduced, because the need to maintain strong pressure places extraordinary strain on the pronating index finger, impairing the movement.

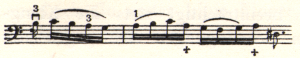

While a passage like this one can be played at M.M. ♩ = 152 at the frog with support from the index finger, it requires considerable pressure from the index finger to get the same volume at the tip.

In order to transfer the maximum pressure from the arm to the bow stick through the pronating index finger without loss of force, we must be careful to avoid extreme pronation, i.e. strongly rotating the forearm inwards. This, as we have learned in previous chapters, hinders the unimpeded transmission of force (aside from the fact that the arm’s mobility would also be exhausted, as well as the effect of force).

We must especially avoid this pitfall when playing at the tip. We can achieve this by simply following the rule that the wrist must not bend! (See image 9 of the Appendix.) Any lowering of the wrist towards the tip reduces the force to some extent during a steady full-bow stroke; here, this is not so disastrous, because the force changes direction at the moment of the up-bow, and any change in tension implies a recovery for the arm and allows for the release of new energy. But when it comes to rapid, powerful détaché above the middle of the bow, it is very important to avoid any loss of power. This goal can best be achieved by keeping the right hand in an arch-like configuration, as shown in the illustration above. This has two effects: first, the prevention of excessive pronation, and second, an increase in individual finger strength.

We can see in image 12 of the Appendix that the wrist has assumed a “middle” position on the A-string, so that if we bend the fingers at the base joint and slightly raise the wrist, we can access the D-string. The height difference at the frog between the two strings is approximately 6-10 cm when playing at the tip. This is the greatest deflecting movement that we can achieve on the cello purely through compensatory raising and lowering movements of the fingers (primarily the fingers, secondly the wrist).

With the help of this special mechanical arrangement, the forearm can remain in its position during bowing and execute a horizontal movement, while the bow can touch the adjacent string without slanting. Image 53 of the Appendix illustrates how the extreme tip is reached by inclining the wrist towards the side of the little finger (not by bending the wrist, which would exhaust the direction of the pronation and partially break the force!).

Let us now consider the

Détaché in the middle of the bow

With the previous analyses of détaché at the frog and tip, the conditions for détaché in any part of the bow are comprehensively established. We can easily determine how to execute a détaché in the in-between parts of the bow through approximation and adjustment. Détaché in the middle of the bow is the most common. The techniques we apply for a good-sounding détaché in the middle of the bow are similar to those for spiccato (refer to the relevant chapter). However, the impetus here comes from the upper parts of the arm and the shoulder, without the free “swinging” that we would use in off-the string strokes. Instead, we must exert continuous pressure on the strings so that the bow hair can adhere to the string. This pressure is less than at the tip, but greater than at the frog. The movement of the fingers and wrist is very similar to that of a bow grip change; the involvement of the wrist is even less in this movement pattern. One should focus more on the lifting and pushing motion of the arm, which moves the bow-holding hand forward and backward, rather than on wrist activity, which needs to be minimal.

Executed at a fast tempo, the arm movement decreases in favor of the hand movement. But one should always study détaché in the middle of the bow by first performing it slowly and with ample arm movement. This generates the momentum that positively influences our tone quality, whereas a détaché led mainly by fingers and wrist from the beginning sounds rather dull and lifeless and can easily lead to unpleasant extraneous noises. The immediate causes of these unpleasant sound effects are: first, the bow hair gripping the string too suddenly and forcefully; second, the bow hair is angled (i.e. not perpendicular to the string). As a result, the string cannot immediately vibrate to its maximum capacity, and the constant change of the bow’s path (i.e. “sawing” the bow in all directions) during up-bow and down-bow strokes prevents proper tone production.

The regular “sawing” motion is not as detrimental as the irregular changes of the angle between bow and string that are caused by excessive movements of the wrist. Occasionally, we will deliberately deviate from the right angle between bow and string for a special sound effect, a diminuendo, or to get the bow closer to the fingerboard. But a constant unintentional change of angle during a bowstroke always impairs the sound effect, because opposing vibrations develop that interfere with each other.

The main task in détaché in the middle third of the bow is to ensure that the bow remains relaxed enough, at any degree of bow pressure, to allow all compensatory movements of the fingers to occur with the greatest ease and security. This is especially important during string crossings. A good example of this occurs in Étude No. 3 of Book I of J. C. Duport’s 21 Exercises.[5]

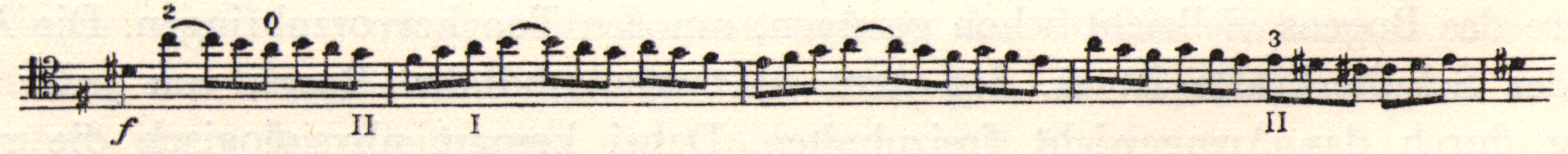

In the following example from Strauss’s Don Quixote theme, we need great expressive power, which we can achieve with détaché in the middle of the bow and ample use of the arm.

The détaché technique offers the perfect opportunity for this. By allocating a larger amount of bow to each note, we can harness the energy of our arm movement for notes we wish to emphasize, while interpreting the less emphasized notes either with the same amount of bow but with reduced pressure, or with less bow but the same pressure.

Occasionally, we find ourselves in the pleasant situation of being able to exploit favorable mechanical configurations of the bow stroke for musical interpretation, e.g.

The accents at the tip with an upstroke require a skillful application of force through pronation, combined with strong forearm stroke, while the string crossing must be done with active finger movements and wrist pivoting. Rhythmically, this passage is also significant: by slightly lengthening the duration of the stroke on the accented notes and shortening it on the subsequent ones, the downward movement in the melodic progression becomes even more pronounced (i.e. agogic accents). We must also consider that the lower third of the bow is most conducive to the application of force. To execute the détaché stroke evenly and rhythmically, we must therefore keep the dynamics under control. Proximity to the frog, however, requires subtle finger adjustments in combination with shoulder activity, and that elbow rotation be eliminated where possible.

Thus, one might say, the outward appearance of the movement already points to the meaningful interpretation of a work that aims for grandeur, such as the aforementioned Bach C major Prelude.

The very first measure, with the C on the A-string as the starting point and the descending sequence of notes to the C two octaves lower, requires a deliberate, dynamically balanced bow movement. Use equal amounts of bow for the initial C and the two following slurred notes; the same duration for the latter! Capture the low C with all of the bow hair!

As the second measure progresses, add strong rhythmic emphasis through secondary accents, which express the rhythm even more strongly. Move your arm on the C string in the direction of the bow and the grip change! (This involves the upper arm rotating backwards, with flexion and extension of the metacarpal in an upward diagonal direction!) The movement of the upper arm on the D-string occurs more through lateral lifting than by rotating backward, with the wrist effectively oriented upward! (Adjust the hand more horizontally!)

Lead the upper arm diagonally upwards and outwards on the A-string to the right. Pronate your forearm sufficiently to facilitate a smooth grip change. From page 17, seventh system, to the first E of the third measure of the sixth system, play quasi in the character of a second keyboard manual.[8] Move more towards the middle! Lift the weight off the string with the shoulder. The bow is guided by the whole arm. The entire arm system moves in a springing, diagonal motion from front left to back right.

In the second bar of the eighth system[9] we will use a kind of “soft spiccato” to make the string crossing as easy as possible.

In the seventh-from-last and sixth-from-last measures, perform a powerful détaché in the middle of the bow with energetic hand and finger coordination! Without slanting the bow! You should therefore use a rotational movement of the thumb around the bow stick to achieve the bowing position! Go back to the middle of the bow!

The Courante of the same suite offers examples of the union of two detached notes within the same bowstroke, e.g.:

which creates a special sound effect. Other examples of détaché with particularly soft tone production include the third movement of Brahms’ F major Sonata:

This passage is best played between the lower and middle thirds of the bow, with plenty of upper-arm movement. The appropriate tone color is achieved with gentle pressure of the bow on the string, supported by the shoulder. A distinctly détaché passage can be found in Brahms’ E minor Sonata, Allegro, final movement:

Similarly, the following passage from Marcello’s Sonata in F major.[10] Both passages are best performed energetically and with rhythmic control around the middle of the bow, using broad strokes of the forearm. The correct dynamic use of the arm is of particular importance for détaché. First, this is where most violations of the rule of drawing the bow at a right angle to the string occur. (As we have already mentioned, this detrimental skewing affects tone color and projection; its cause lies in incorrect movement stemming from the improper application of force.) Secondly, due to the characteristics of the stroke (i.e. where bow balance plays a less significant role), the détaché stroke must be made to sound good in every part of the bow. A flawless spiccato, on the other hand, can only be produced near the balance point of the bow at rapid tempos. Reducing the arm’s force enough to produce a bouncing motion must be done in the correct proportion to minimize arm movement. Once the right proportion between force and movement amplitude is precisely achieved and centered around musical feeling (which comes through experience), the movement “sits,” as musicians say. A good spiccato can always be reliably achieved with the same means. In spiccato, bow control requires a constant amount and force for the same tempo.

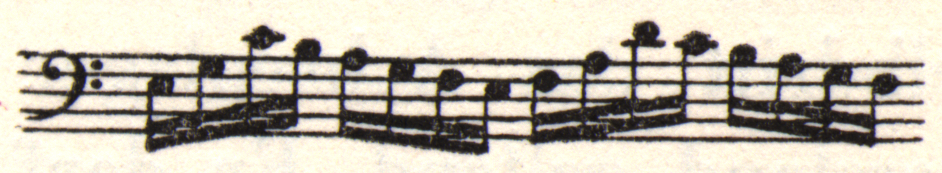

Not so, however, with détaché! To play the first two measures from Beethoven’s Sonata in D major, Op. 102 at the same volume, we need very different amounts of force at the tip and the frog.

Because the bow’s weight does not distort the hand position, the natural hand configuration when the bow is at the tip corresponds to the relaxed final phase of a movement.

Near the frog, the bow’s own weight is already too heavy for producing soft dynamics. Therefore, the pressure must be reduced either by actively lifting part of the bow’s weight from the string with the fingers, or by managing bow changes at the frog through the grip change technique we learned in earlier chapters. This serves to reduce pressure. However, playing the last musical example loudly in the upper third of the bow requires enormous muscular effort.

Dynamics and the détaché stroke

Applying pressure to the bow using arm strength often disrupts smooth patterns of movement, as we have already pointed out. It is important to remember that when applying force, the player must still strive for fluid movements.

Since détaché is played at various different points along the bow, there are many ways that the improper application of force can inhibit smooth movement.

In the lower third of the bow, we need to partially lift the bow’s weight off the string. This does not require us to rotate the hand and forearm in the sense of supinating, but rather involves a small lifting action by the little finger, which acts as a lever on the short section of bow between the pivot point and the place where the little finger touches the bow.

If you approach the frog on the D-string slowly and want to make a crescendo, observe the following, keeping in mind that the slower you move the bow, the more the forces acting on the bow resemble the static forces of simply holding the bow motionless in the air. This means that toward the end of a bowstroke at the frog (unless there is further movement through a down-bow stroke involving the grip change technique), the fingers of the bow hand work almost exactly as if you were simply holding the bow in the air.

In cello playing, the function of the index and little fingers varies depending on the string being played. On the A-string, the index finger guides the bow direction and the slight curvature of the top joints around the stick prevents the tip from tilting downward. On the C-string, the little finger is more responsible for controlling the direction of the bow.

The little finger also ensures the transmission of the supinating force, which acts against the thumb in every case. The thumb, in turn, provides counter-support for the second and third fingers. Between these two middle fingers and the thumb, which together form a fulcrum, there is always a certain noticeable frictional resistance. However, it must never be so great that the “leverage” between this fulcrum and the index or little finger cannot take effect.

This is precisely the meaning of the relaxed bow grip: every individual force is measured according to its relation to the total effort and the degree of dynamic bow pressure on the string. The pressure on the string represents, in a sense, the result of all the forces of the arm. In relaxed bowing, we must minimize exertion, otherwise the delicate interplay of double weight transfer, grip change technique, and finger flexion and extension is not possible. If we press the bow between the thumb and the two middle fingers, this results in an entirely unnecessary use of force, especially at the frog, because here we are dealing only with the weight distribution of the bow without any additional pressure effect on the stick. In fact, we even take some of the bow weight away from the string. One could, of course, guide a rigidly clutched bow over the strings by lifting the entire arm from the shoulder. We would normally do this to achieve certain sound effects, but not during normal bowstrokes.

Therefore, gripping the bow too hard is a waste of strength, as the individual forces on the forearm partially cancel each other out in their opposing effect. (Anyone who constantly holds the bow with excessive thumb pressure and does not relax it even where only slight counterforces are acting—such as at the frog—sometimes incurs a repetitive stress injury in their thumb. We can see that physiologically correct playing not only achieves the best sound production, but also represents the healthiest way to make music.)

Sometimes, however, when we are playing pianissimo or with an extremely delicate sound, the normal finger adjustments described earlier do not work very well, especially in faster bowstrokes (or when “bowing on one hair,” so to speak). In such cases, we must “carry” the bow over the strings. We can do this by lifting the whole arm along with the bow from the shoulder (though do not confuse this with hunching the shoulders!). The upper arm is connected by a ball-and-socket joint in the shoulder; this anatomical feature allows free rotational movement in all directions. The shoulder joint thus provides a pivot point to use the entire arm as a lever. The arm works as one unified lever while the shoulder muscles remain relaxed. This weightless effect is accomplished by using the shoulder musculature to support the upper arm.

It seems paradoxical, but in reality, the bow grip should be somewhat firmer in pianissimo than in mezzo forte and forte under these conditions. Note that the entire arm, along with the stick of the bow, again forms a single fixed lever. This is an exception to the rule that the hand should form movable link between the arm and the bow.

Movement processes develop quite differently, however, when we apply stronger force to the bow, especially in forte passages toward the tip of the bow.

At this point, we must re-examine Steinhausen’s theory.

In his Physiology of Bowing, Steinhausen speaks of the upper arm and shoulder as force levers and the forearm and hand as force transmitters. He analyzes the physiological conditions under which violin playing operates. From his conclusions—which are somewhat one-sided in assigning the upper arm the role of power source while wanting the forearm to constantly serve as power transmitter—it’s clear that he based his research on more basic violin playing techniques. As the primary auxiliary movement for bowing, he defines forearm rotation—which functions as supination on every up-bow and pronation on every down-bow—as what gives bow technique its essential momentum. However, he dismisses all wrist and finger activity; he also does not understand understand the reactive responsiveness of the finer movements of the hand and fingers that we have described above.

To summarize Steinhausen’s theory in a formula: the power source of the playing mechanism should always reside in the upper arm and shoulder. But this simple principle alone cannot solve the problems of highly developed violin technique.

However, these conditions apply even less to cello technique, since it operates under different premises from that of the violin. Beyond the fact that all movements occur in completely different planes and directions—meaning the basic movement patterns are different—the dynamic forces acting on the bow are of an entirely different nature. In other words: the visible movement patterns are different, and generally much greater forces are required in cello playing.

The difference is best illustrated by the fact that forearm rotation plays a considerably less important role in cello playing than in violin playing. Because greater exertion is required to play the cello, we deal more with sustained forearm pronation, or the readiness to pronate.

From this perspective, Steinhausen’s principle alone does not work for cello technique. We have established that with a freely swinging spiccato stroke, both the impulse and the downward pressure can originate from the upper arm, because the force required is very modest. Likewise, we play détaché strokes in the lower third of the bow using forces from the shoulder and finger movements (for mechanical reasons, to ensure straight bowing). Here too, the force expenditure required is quite modest. But when we must produce a powerful forte at the tip (as in the opening of Dvořák’s concerto, for example) or play détaché passages spanning several measures in forte at the tip, considerably greater force is required.

Two approaches are possible:

- Either the forearm locks into a pronated position on the bow so that the partial forces of the forearm combine into a single force. The upper arm then participates more intensely in the exertion of force, and the grip becomes progressively tighter since the capacity for pronation is exhausted. However, the increased upper arm tension restricts free shoulder mobility. Instead of perpendicular bow pressure on the string, lateral pressure effects develop, and this impairs the string’s vibration (see Jahn, Basics, p. 52). This pattern shows up when the index finger gets stuck around the bow stick, and the base knuckle joint collapses under pressure. The individual fingers progressively lose their ability to function normally.

- In an alternative approach, the forearm’s lever forces remain controlled within limits. Pronation acts on the bow without leading to extreme forearm rotation. Here, the application of force comes primarily within the forearm. The upper arm remains free from excessive tension, and shoulder forces can be utilized without hindrance for bow momentum. Furthermore, pressure can act perpendicularly on the strings, which is most favorable for vibration control and tone production in every case, but becomes absolutely essential when playing with full hair contact at loud dynamics.

The second method compels the fingers into increased activity, in accordance with our theory of responsive playing technique. We can avoid gripping the bow too heavily while still producing a powerful, resonant tone. Now (as we have seen in the chapter on the physiology of bowing technique), flexion and extension of the fingers at the knuckle joints also involves the so-called short muscles of the hand (the musculi interossei and lumbricales), so that by extensively training the fingers to be active, we can relieve the upper parts of the arm. This has an extraordinarily beneficial effect on the mobility and momentum of the entire system, and removes the heaviness and clumsiness in bowing that is typical of many cellists.

Cello bowing mechanics work a bit better than violin bowing in some ways. (Cellists can do some bow strokes that violinists cannot, such as arpeggiated passages going through the lower to the higher strings on an up-bow staccato. A technically skilled cellist can play these in both bow directions!) The main thing that stops cellists from fully developing their technical potential is using their arm muscles improperly…

In reality, it is not always possible to implement theoretical ideals perfectly. Take a simple bow stroke—for example, playing piano at the frog and getting louder as you move to the tip. During this one stroke, we go through the whole range of force application. At the frog, we partially release the weight of the bow; at the tip, we reduce downwards pressure but compensate by using pronation to retain contact and control. We apply these principles smoothly and continuously as we transition from frog to tip.

In practice, we get close to the technical ideal when we smoothly execute the grip change technique during bow changes at the frog (which also reduces pressure), while maintaining a flexible curvature of the fingers and not allowing the wrist to bend as we approach the tip of the bow.

This is why executing a full bowstroke at a slow tempo—down-bow with crescendo, up-bow with decrescendo—is so difficult. For the détaché at the tip, and of course for simple bow changes at the tip, the challenge is to keep the wrist loose and flexible despite applying force.

It is clear that the only quick way to learn uninhibited, automatic technique is to consciously study all phases of movement from the beginning, and train the muscles to use exactly the right amount of force while keeping the ear focused on making sure all physical movements create good tone production that serves the musical interpretation.

- i.e. when the bow is not perpendicular to the string. ↵

- Becker uses the term schabenden Cello, a "screeching cello" or "howling cello." ↵

- Translator's note: Becker refers to Etude No. 6 from Jean-Louis Duport's Essai sur le doigté du violoncelle, et sur la conduite de l'archet (Imbault, 1805). Martin Berteau (ca. 1691-1771) is considered the founder of the French school of cello playing. ↵

- Becker uses the word Dynamik, which can refer to musical dynamics, but in this instance seems to refer to "dynamism," or "the action of forces." ↵

- Becker refers to Jean-Louis Duport: "J. C." is a mistake or a typographical error. ↵

- Translator's note: "Allegro maestoso" is not present in any of the eighteenth-century manuscripts of the Bach Suites. It is Becker's own suggestion in his own edition of the Suites, published by Peters in 1911. ↵

- Translator's note: Again, Becker refers to his own Bach edition. ↵

- This passage refers to mm. 65-71 of the Prelude of Bach's Suite No. 3. ↵

- i.e. measure 74 of the Prelude. ↵

- Benedetto Marcello, Sonata Op. 1, No. 1. ↵