The “Grammar” of the Playing Process

If we can justifiably describe music as a language, then we may also speak of the grammar of instrumental technique. Just as one cannot learn a language correctly—whether spoken or written—without mastering grammar, one cannot make music without understanding mechanics. And just as mastery of grammar enables “ornate syntax,” grammatically sound mechanics allow musicians to consciously create artistic compositions.

No poet or orator would disregard the rules of language; mastery of these rules is a self-evident prerequisite for both. Why should music be an exception?

If knowledge of the “grammar” of playing procedures were more widespread, most ungainly errors and misapprehensions could be avoided. Beyond the frequently encountered errors in the “declamation” of music, intonation alone would improve considerably through adherence to foundational principles.

Most intonation errors are primarily the result of poor (or rather, inappropriate) hand positioning. A secondary cause is the uncertainty about whether to use a closed or extended hand position when executing position shifts. Knowing which to choose each time prevents serious intonation errors.

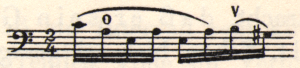

The following measures from the present author’s Spezial-Etüden, no. 3 illustrate several principles:

a) The hand must shift from the narrow position to the wide position. This shift is completed on the low C-sharp of the first measure: first use the closed hand position, then extend to the wide position. Do the same in the third measure on D-sharp and in the final measure on the sixteenth-note G-sharp at the beginning of the second half of the measure. Here, the turn occurs on the second finger, which enables the fingers to cleanly grip the following notes played in the wide position: D-sharp, C-sharp, and B.

b) The systematic change of position. In the first measure, the first finger moves inaudibly from an extended hand position in half position from G-sharp to the (imaginary) auxiliary note B in second position using the close hand configuration, thereby ensuring the intonation of D and C-sharp. In the second measure, the position shift goes to the imaginary auxiliary note D-sharp (first finger). Here, two close hand positions follow each other. However, in the next position shift (fourth finger from F-sharp to C-sharp) we must transition from the closed position to the extended position. The transition from the second to the third measure is interesting: the last two sixteenth notes of the second bar are still in the previous extended position from before, so that getting to the D-sharp at the beginning of the third bar only necessitates bending the first finger.

We can find a good example of a place where we have to adjust the hand position in the first of Schumann’s Five Pieces in Folk Style.[1]

Without this adjustment, the intonation cannot be flawless unless the player has an unusually large hand that allows them to execute both closed and extended hand positions in the same configuration.

A normal hand cannot achieve this.

Even this well-known run from Popper’s Vito[2] contains an example that proves that we must not only take care to land cleanly on the first note of the new position, but simultaneously get the hand into the appropriate extension and configuration to land correctly on the sequences of notes in different positions on the fingerboard. (Note the two different fingerings in the second-last measure of this passage.)