The Martelé Stroke

The essential characteristic of the martelé stroke is, as the name suggests, its distinctive, hammering character. Martelé is a stopped stroke: between every two notes, there is a pause. Some authors distinguish between long and short types of strokes; the martelé is the latter.

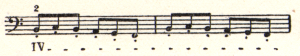

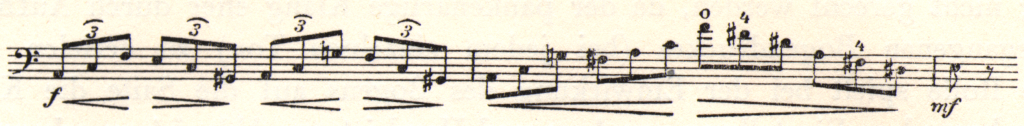

In order to achieve the sharpness and shortness of tone characteristic of this bowstroke, the student should initially play this excerpt from Grützmacher’s Technologie, Part 1, Étude No. 2,[1] using full-bow martelé strokes:

![]()

The tempo should initially be so slow (approximately M.M. ♩ = 72) that the bow is only used for a quarter of the value of the note; the remaining time is reserved for rests, i.e.

![]()

Here again, cello mechanics differ from those of the violin. Cello playing requires greater bow pressure than violin playing; therefore, the bow pressure should not be completely released during the pauses.

Analogous to other processes in bow technique, the bow pressure must be generated, if possible, by peripheral muscles (i.e. pronation of the forearm). In this way, we create a favorable situation for the rapid martelé and the staccato resulting from the martelé. The latter is usually best achieved by keeping the shoulder as free as possible from increased tension.

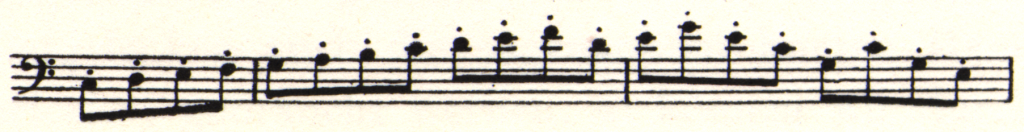

After practicing slow martelé strokes using the whole bow, proceed to faster, shorter ones. For example, in the same Grützmacher composition, at M.M. ♩ = 100:

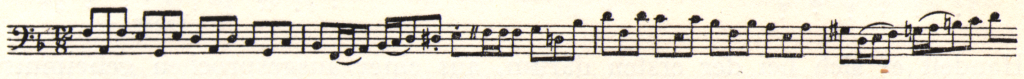

Here are some other characteristic passages from the literature.

Haydn Concerto, first movement:[2]

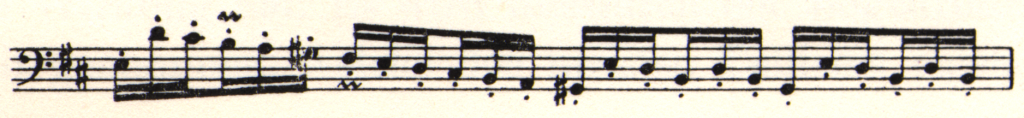

From Romberg’s Concerto No. 3:

From the first movement of Brahms’s Double Concerto:

In addition to the aforementioned martelé stroke, there are variations of this type of stroke, which are created by modifying the bow pressure, speed and choice of sounding point, and which lead in various gradations to the détaché or spiccato strokes.

From Strauss’s Don Quixote, martelé-détaché:

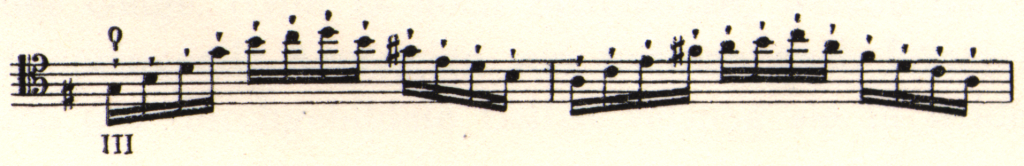

The short notes in the second half of the bar in the following example from the last movement of the Dvořák Concerto also use a martelé-détaché. These are very abrupt movements—do not release bow pressure during the pauses!

A “thrown” détaché, or spiccato, can be found in the last movement of Schubert’s Trio in B-flat major:

![]()

By using the martelé stroke very close to the frog, we can get a special sound color resembling that of the timpani. We will call this the “timpani stroke” and dedicate a separate discussion to it, as it has been previously unknown and therefore never addressed.

The “timpani” stroke

Just as the composer’s imaginative soul strives insatiably for new tone colors (the ability to mix timbres is a component of their individuality), so too will the gifted performer aim to enrich their “tonal palette” to enhance the expressiveness of their instrument. While the rich nuances of properly-executed vibrato and portamento already provide us with a valuable way to create musical character, the bow’s possibilities for tone color are almost inexhaustible. It is first and foremost the interpreter of our emotions, whether they seek elegiac expression or indulge in bubbling cheerfulness.

A particular sound effect results when we play detached notes and let the bow act on the C-string with short, sustaining strokes, right at the frog, using all the hair, and close to the bridge. It can hardly be called bowing anymore, but even the word “beating” would not do justice to the process, since the timpani-like sound is more likely achieved by releasing the previous bow pressure (for each individual note). An important role is played here by the bow’s effect on the string in the shortest possible time. The special positioning of the hand and arm can be seen in image 54 of the Appendix.

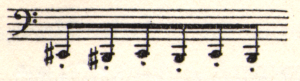

The “timpani stroke” can be used to great advantage in, for example, both the third movement of Brahms’s F major Sonata and the last movement of his Double Concerto to create a characteristic performance. Here are the two examples:

![]()

In the first case, it involves initiating a significant dynamic increase from a distinctly mysterious atmosphere—which the timpani stroke effectively supports—while in the second, a humorous passage from the Double Concerto, we can emphasize it in a characteristic way despite the indicated piano, and thus adapt to tone color to that of the timpani.

In the descending sixteenth-note figure, the spiccato gradually transitions into the timpani stroke, which then resonates in all its characteristics from the low E. This stroke can also be successfully applied in the first movement of the String Quartet in A minor, Op. 33, by E. von Dohnányi.