The Portamento

Portamento plays a great role both in the art of singing and in the art of playing string instruments. The attentive listener will be able to observe during the performance of a highly cultivated, intelligent singer—a phenomenon that we unfortunately do not encounter often enough—that they understand how to apply portamento in various forms, according to the meaning of the words that determine the expression of their singing.

The instrumentalist lacks this sure guide: the word—hence the frequent aberrations of taste in so many bowed strings artists.

For the string player, portamento is a musical means of expression in which the mechanical movement of the position shift is regularly utilized in a special way for performance; it is a gliding connection between two notes that are (with a few exceptions) in different positions on the fingerboard.

There are two ways to execute the portamento:

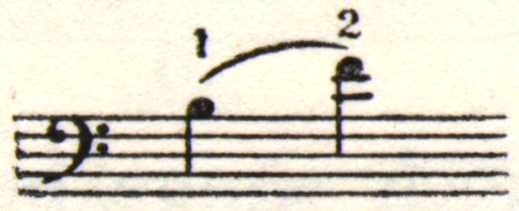

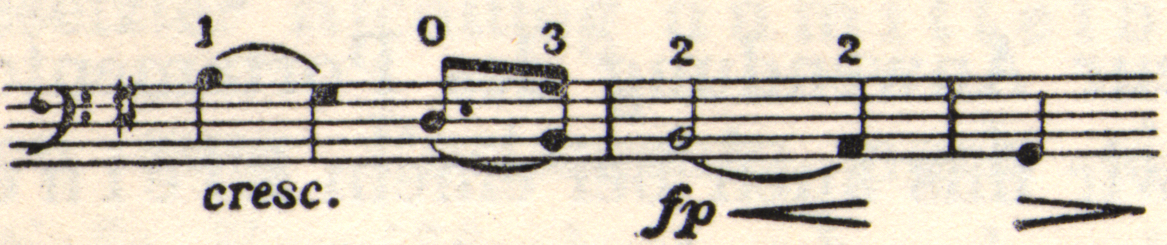

1. With the same finger, e.g.

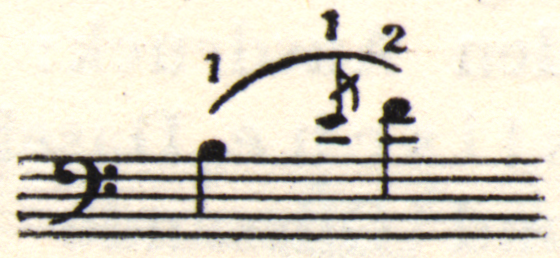

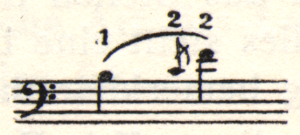

2. Using two fingers, e.g.

For the first type, the connection between notes takes place without interruption.

For the second, we can either (a) slide up on the “starting note” finger to the auxiliary note, E:

or (b) use the “target note” finger for the portamento, like this:

Examples 1 and 2b are more suited for playing in a lyrical style, and example 2 is more for playing in a heroic style.

The cultivated cellist always plays the portamento with a fairly pronounced diminuendo (that is, a decrease in the bow pressure or a reduction in bow speed) during the slide.[1]

When portamento is applied too frequently, or in the wrong place, or even when it is used too intensively, it can distort the performance to the point of ridiculousness. Here, too, as with vibrato, a wise measure of restraint, a subtle, intelligent differentiation, enhances the beauty and meaning of the performance. In addition to the few written rules, there are countless unwritten ones that, guided by good taste, can have an impact here.

Trying to list all the possible ways of using portamento correctly here would be as futile as trying to list all the cases of inappropriate portamento (“If you don’t feel it…”). Nevertheless, we do have certain clues that allow us to establish some irrefutable rules. With their help, we can create clarity in the area under consideration.

- One should, as we have already mentioned, play every portamento with a diminuendo.

- The further apart the notes we want to connect, the slower we should execute the sliding movement, which makes a diminuendo all the more necessary.

- One should never immediately follow a portamento in one direction with another in the opposite direction.

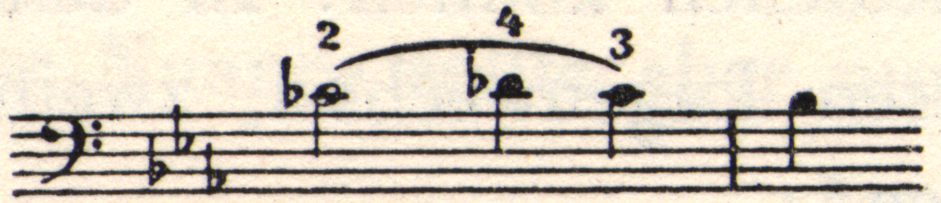

- One should add vibrato to the portamento if you want to portray great passion, pain, deep emotion or the expiration of life force. However, this nuance should only be done from a higher to a lower note, e.g.,

(the third finger slides to the E-flat in second position, whereupon the second finger comes in on D). See also Don Quixote, penultimate bars, p. 254 ff.[2]

(the third finger slides to the E-flat in second position, whereupon the second finger comes in on D). See also Don Quixote, penultimate bars, p. 254 ff.[2]

These are the first general rules we must observe when applying portamento.

Now, here are some special types of it. To understand a very subtle type of portamento, we must temporarily move to a somewhat distant area where we find a characteristic analogy in the French language.

To understand a very subtle type of portamento, we must temporarily move to a somewhat distant area where we find a characteristic analogy—the French language.

As is well known, the French customarily connect the last consonants of one word with the first vowel of a second word—for example, “pas un mot” or “dans une maison”—when linking them together. For the non-French speaker, this linguistic nuance, which is called the “liaison,” presents some difficulty. Either they omit it altogether, or the make too pronounced a connection to the second word by articulating the S too sharply or harshly. Both ways are wrong. The correct way is somewhere in the middle. Therefore, there should be no interruption between the two words, but rather, a gently sliding, soft connection!

The nuance of speech is best characterized by the “small” portamento, which can be effectively applied over short distances (e.g., the interval of a second), and which can also be applied at the attack of a note, at the beginning of a phrase if the musical diction permits this somewhat sensual nuance to color its performance (comparable to the “sobbing” articulation of Italian singers. Think of Caruso!)

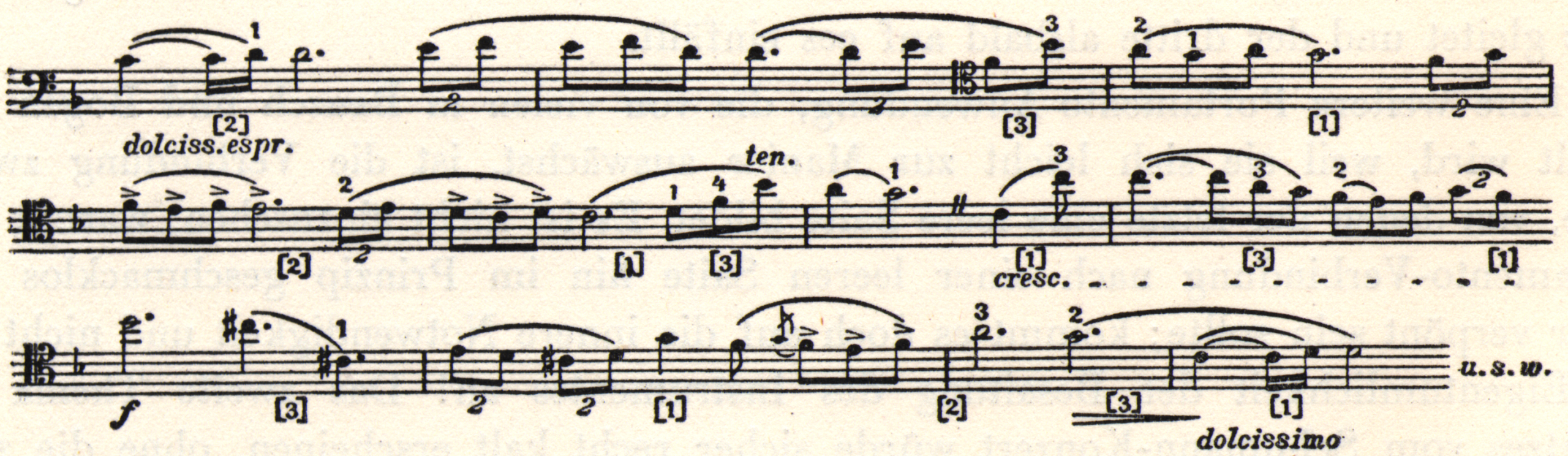

The second theme of the first movement of the Lalo Concerto provides a good example of the three different types of position changes, which are the main—though not the only—opportunities for applying portamento. (We say “not the only opportunities” because we can also use portamento for small intervals such as seconds within a single position!) In this theme, we find opportunities first for inaudible position shifts, secondly for the application of small portamento, and third, for large portamento:

The Arabic numerals in parentheses indicate which type of position change should be used to play this theme in a tasteful, noble way.

For shifts covering large distances, as in these examples:

we can also delay the portamento until the second or last third of the distance covered if we find the large portamento undesirable, being too noticeable. Constant audible sliding when changing positions is intrusive and repulsive; it’s like a mark of Cain showing lack of culture that performers carelessly or unknowingly brand upon themselves! The subtly applied, noble portamento, on the other hand, is able to color the performance in such a variety of ways that the receptive listener cannot escape its charm.

From the earlier numbered list of rules for portamento, the attentive observer will recognize that techniques of convenience (“safety” fingerings and so on) should not come into our interpretations according to aesthetic principles. The solution is to renounce cheap effects on one hand, and technical shortcuts[3] on the other. Therefore, one should examine where a portamento would be appropriate, since it is not suitable for every position shift. One should trust one’s ability to shift inaudibly, i.e. seamlessly and without portamento, even when covering greater distances, for the sake of “cleanliness” (!).

On the other hand, there are also passages that absolutely demand portamento, and where even a well-trained singer would never fail to use it, but where a change of position normally doesn’t take place. Here, we must specifically create one; for example, in the twelfth bar of the Adagio of the Dvořák Concerto. By changing to another finger on B, we are able to create a beautiful, intense portamento, which adds considerable warmth to the entire passage.[4]

Such cases also include the following (from Hugo Becker, Romanze in E-flat major, Op. 8, seventh-to-last measure), where portamento from D-flat to C-flat, in which the fourth finger slides only to the C and the third immediately drops onto C-flat.

Another application of portamento (that many condemn outright because it can easily become gimmicky) is the connection of two notes, the last of which is on an open string. It’s hard to see why a portamento going to an open string should be condemned as tasteless; after all, what matters is the inherent necessity, not the peculiarity of the instrument’s stringing!

The second theme of the first movement of the Schumann Concerto would certainly appear quite cold without the tender “liaison” from G down to A (observe the exact fingering and portamento notation):

Without portamento from B-flat to D in the following phrase from the climactic section of the Romanze, which demands an inspired, passionate expression, would be completely flawed:

Similarly, in the following short motive from the Adagio of the Locatelli Sonata (page 7, second measure), the note B requires a slide (albeit a very delicate one) to the open A-string.

Overly frequent or indiscriminate use of this nuance is, of course, wrong. Here, too, only good taste can protect us from mistakes; moreover, such expressive devices must be executed to perfection, otherwise they seem ridiculous or repulsive.

Finally, let us mention a portamento nuance that produces a very beautiful effect when the trill note is continued upwards:

The trill should be played without a Nachschlag; the first finger slides slowly from D to E; upon the repetition of the E, we change finger. The bow makes a strong diminuendo, but gives a gentle accent to the repeated note.

- Becker's note: "We should distinguish between the emotionally expressive portamento—with its audible pitch changes—and the simple sliding of fingers along strings to shift from one position to another. This finger sliding is merely a mechanical necessity that should be made as acoustically unnoticeable as possible.

Following the suggestion of my former trio colleague [Carl] Flesch, I reserve the term 'glissando' for this type of sliding movement. The glissando, therefore, has no real acoustic purpose! The common confusion between the terms portamento and glissando arises because both involve the same mechanical process.

Put another way: when we hear a glissando, even though the player has not intentionally played a portamento, it reveals a technical flaw—either in the bowing or from a hand that is moving too slowly. Unfortunately, this clearer terminology won't easily take hold anytime soon, since musicians have long used 'glissando' when they actually mean 'portamento.'"

- Becker refers to the last two notes of the solo part (beginning six measures before the end of the work), where Strauss ends the phrase with the interval of a descending octave, marking the two notes with a line that indicates portamento. ↵

- Becker uses the German idiom Eselsbrücken, "donkey bridges," meaning mental shortcuts or mnemonic devices that serve as memory aids. ↵

- Becker's note: "See my analysis of Dvořák." ↵