Supporting Open Textbook Creation

19

Stefanie Buck

Sustainability in OER can take on many dimensions. As Downes (2007) points out, it’s important to look at the big picture of sustainability and the “total cost of ownership” of OER which includes not just the creation of the OER but the ongoing upkeep and maintenance. Sustainability refers in part to the longevity of the program-how will you use the funds that you have to create and maintain OER? There are other considerations too. Wiley’s (2007) On the Sustainability of Open Educational Resource Initiatives in Higher Education is an excellent resource that summarizes some of the challenges around the sustainability of OER.

Wiley (2007) defines sustainability in OER initiatives as:

“… the ability of a project to continue its operations. And certainly, the idea of continuing is a critical part of the meaning of sustainability. However, we cannot place value on the simple ongoing machinations of a project and staff who produce nothing of value. So the definition of sustainability should include the idea of accomplishing goals in addition to ideas related to longevity. Hereafter, sustainability will be defined as an open educational resource project’s ongoing ability to meet its goals. [emphasis added]”

Institutional Support

First, it is important to acknowledge that without institutional integration on all levels, an OER program cannot be sustained (OECD 2007). One of the main components of a sustainable OER program is having the support and infrastructure in place to help these projects develop (Desrochers 2019). It is recommended that an institutional OER policy be developed to affirm the institutional commitment to OER as well as lay out the purpose and expectations for creating and implementing OER in the classroom (Desrochers 2019). Having these supports in place will make it easier to encourage faculty to experiment with OER.

Resources

Funding is usually the first thing people think about when they hear the word sustainability (Wiley 2007). Free-to-use resources are not free to create. As the project manager, you are likely aware of this. It is not, however, always obvious to everyone else just how much goes into creating and sustaining OER. Even projects that have an enthusiastic institution that provides “start-up” funding can falter without additional or sustained support (Annand 2015).

There are many potential funding models out there, but funding typically comes from the institution or a government or non-governmental organization (NGO). Examples of funding models include:

- Community-based donations

- Institutional (which may be at the institution level, department level, or from a specific support office such as Academic Affairs)

- Government

- Philanthropic/NGO

- Endowment

- Commercial (e.g., Lumen Learning)

- Partnerships (e.g., OpenStax’s strategic partnerships with commercial partners)

One additional and more unusual model is the Increased Tuition Revenue through OER model described by Wiley, Williams, DeMarte and Hilton (2016) which essentially works on the premise that if fewer students are dropping out or withdrawing because of the cost of textbooks, having an open textbook in a course should increase the number of students who enroll and persist. This translates to increased tuition revenue; revenue which could be used to fund OER initiatives.

Lashley et al. (2017) wrote an excellent article about many of these different funding models that are possible. In this section, we will not go into each model but instead, list some areas of sustainability to consider when you are budgeting for projects and the program.

Funding for Projects

Each project will likely have its own budget and the funding may come from different or multiple sources, such as institutional funds or a grant or both. However, in many cases, these are one-time funds, and the bulk of the funding goes toward faculty incentives. (See Lashley et al. [2017] for more on sustainable means of incentivizing faculty). Faculty incentives can range from $500 to several thousands of dollars. Financial incentives are important to many faculty as it allows them to buy out of their course time or hire assistance on the OER project.

However, it is not just faculty incentives that need consideration. Financial incentives are only one type of cost that an OER project has. Ancillary costs need to be factored in, and you may want to build the sustainability of the project into the grant in order to keep up the quality of your product. For example, your project budget may include the following:

- Author fees/Other Payroll Expenses (OPE), such as fringe benefits

- Copyediting

- Honorariums for peer reviewers/contributors

- Funding to keep the project up to date

- Travel to conferences, etc.

- Software or technology costs for production and/or hosting

- Media production (audio, video, graphic design)

Wiley (2007) points out that there are other ways of sustaining an OER project or program besides money. For example, he notes that many open software projects are created and maintained by volunteers. This may prove challenging but is worth consideration.

Funding for Programs

What happens when the money runs out? Will your program be dissolved? Grants and funds are available from federal agencies and institutions, but those are not necessarily guaranteed year to year. As you develop your program, consider the funding models available to you and how they can sustainably support your program over time. Keeping track of your project expenses will help you determine your annual budget.

You will most likely be the person not just charged with managing the money but also may be charged with finding the money to keep the program going. To do this, you want to build a culture of sustainability, which is discussed elsewhere in this text, through partnerships and relationship building at your institution. Sustainability is not an afterthought but needs to be built into your program from the beginning.

Budget considerations:

- Technology infrastructure: Even within institutions of higher education, the department or college often has to “pay” for the technological support it receives. Or you may be hosting on a platform like Pressbooks. In either case, if this is going to be a recurring cost, it needs to be accounted for in your master plan.

- Professional development and training: for your team or your authors. Things change and you need to keep up, or you may need to provide some training for your authors. You may want to support faculty travel to conferences.

- Graphic design and media support: If you do not have the capacity to do this in-house, then you may have to outsource some of this work or you may need funding to purchase a specific program for graphic design or media support.

- Special projects: Sometimes a unique opportunity comes along. You may want to set aside a little of your funding to cover it and it may be helpful to keep copies of unfunded project proposals in case there are some unexpected resources made available in the future.

Technical Sustainability for Use and Reuse

Technical sustainability refers to both how the creation of the items is accomplished and how they are distributed and made available for reuse. OER are only open if they can be edited, updated, revised, remixed, and shared (Amiel 2013). Technological issues can get in the way, not only when choosing the content creation tool but also in the method of distribution. For example, you may create a video as part of your OER and post it with an open license on YouTube, but unless the actual raw video footage is available, it may be difficult for others to revise or remix the video. Proprietary formats can cause issues with the openness of a resource. If the item needs specialized software to be edited, it can limit the reusability of the work in the future (Ovadia 2019).

Interoperability is key, as is the ability to update works using different tools and to reformat a work if the file format is no longer used (technological obsolescence). When an OER is created, it should be made available in at least one format that is easily editable. This can be facilitated by providing users the ability to download local copies of an item in multiple formats. The technology you use to create and distribute an OER should not prevent the 5Rs from happening with your content (Ovadia 2019). See the ALMS framework for help when considering which tools/platforms to use (Hilton et al. 2010).

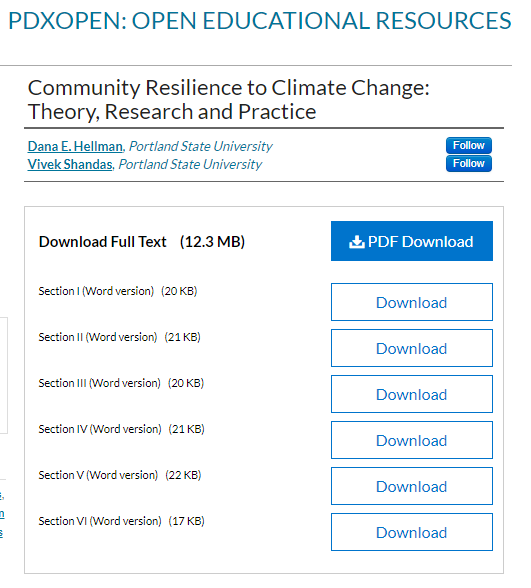

PDXOpen, the OER program at Portland State University, for example, provides both the PDF and the Word versions of the work for easy editability. Other institutions use GitHub or Google Drive to offer editable versions of a text or other resource.

Sometimes it is necessary to have a technological barrier to your content, and it’s important to consider how individuals can access the work if there is a restriction. For example, an instructor has provided the answer key to an OER lesson. The lesson can be downloaded by a student or instructor, but you may not wish to give students access to an actual answer key. How will other instructors who use the work gain access to the answer key? Will they email you or be able to gain access to a shared folder? How will you regulate this? If your OER becomes popular, you might be fielding many emails from instructors asking for the answer key. Each institution will have a different solution to this problem. Working with your IT department can help you set up a system that works for you.

Archiving

When a new edition is released, create a review process to determine when works are out of date or no longer being updated and need to be archived. This is called a retention schedule.

- Make it clear the text is a new edition or version.

- Put a link to the new version somewhere in the old version.

- Indicate somewhere in the old version that this (old) version is no longer being updated/corrected/fixed and refer users to the new edition/version.

- If the new version will be replacing the old version, consider keeping copies of the old version in a repository for posterity. Keep in mind someone may be linking to the old version.

To be sustainable, your technology needs to be stable, maintained, and available. In order to allow others to use and reuse your content, you need a reliable platform. What if the hosting platform goes away? This is a very real possibility. You should have a contingency plan in your strategic planning document in case the university decides it no longer wants to pay for your Pressbooks account, or the open-source software you are using is suddenly no longer being updated. Use the technology available to you, but keep this potential issue in mind as you plan. One way to help mitigate this problem is to host your content in several places, not just one.

This can all sound quite daunting and like a lot of work, which it is. But these are the questions/things to consider when trying to create a new system for publishing/knowledge dissemination/education, and it’s much better to anticipate these situations early on than having to deal with them once your program is in place.

Creating and Sustaining Quality Content

Among the issues that often crop up at the end of a project is how will this project be updated or maintained? It’s important for the quality of the content and the sustainability of your program that the text be accurate and up to date. Many initially enthusiastic authors get bogged down with other projects and do not return to the textbook to make important updates or improvements. Production encompasses many aspects, but one of these is proper workflow. Proper workflow can lead to a sustainable product or program. Below are some examples of areas where well-developed workflows will help you sustain your project or program.

Currency of Content

One of the great things about OER, which are usually digital, is that they are easy to update and keep current. It’s one reason why many authors want to create an OER; their discipline is changing rapidly and they want the most current textbook or OER they can get. But someone has to do the actual work. Make it clear early on who is responsible for this work and how it will be done. If you do not, the project is likely to disintegrate.

You may want to set up a form (e.g., Google Form) linked from within the OER and your website where errors can be reported. If the author is correcting the content, then you need to think about versioning (see below). Review this form on a daily basis and make the easy changes quickly (within 24 to 48 hours). This includes errors in spelling or grammar, missing captions, formatting, or layout issues. If the change is more significant, you will need to work with the author to determine how to fix the issue. If authors are responsible for correcting errors in their textbook, you need to be clear that they have this responsibility and set some expectations. For example, you may want to write into your MOU what the sustainability plan of the author is (e.g. review content for updates once a year) but then you also need to hold them to it. It is likely that you will be the one reaching out to authors asking them if they want to update their OER rather than the other easy around, although some creators are very careful to keep their content up to date. You may want to set up a calendaring system with reminders of which OER requires a review so that you can reach out to the author in a timely fashion.

Link Checking

Many open textbooks contain links to relevant content or additional resources. Those links need to be maintained and checked regularly. You can ask your authors to take on that responsibility or you can take it on. Either way, make that clear in the Memorandum of Understanding (MOU). An automated link checking system is invaluable here. You can work with your local IT department to see what options are available. Authors frequently make their text up to date and relevant by including outside sources, such as journals or news articles. In these cases, it may be better to link out to those resources, especially if they are not openly licensed, rather than trying to bring the content into the OER. However, it is best to consult the Best Practices for Fair Use in OER for when to link out and when to incorporate third-party materials (Jacob et al. 2021). If the articles are behind a firewall, make sure to indicate this somewhere in the citation to avoid frustration on the part of the user. Materials behind a firewall (e.g., a list of resources) should be optional and not required. For quality purposes, keeping the links working and accurate is just as important as keeping the content up to date and accurate.

Versioning

Another reason faculty authors like OER is that it’s easy to create a new edition without additional costs to the students. However, there is considerable effort that goes into creating a new edition or doing major updates to a work. Once again, you need some clarity about who will do this and what will happen if the responsible party does not make updates or changes. In some cases, you may wish to include a clause in your MOU that permits you (the publisher) to make necessary changes—even without the author(s)’ permission—if you deem it necessary. For example, the Adaptable Open Educational Resources Publishing Agreement (OEN, n.d.) includes the following statement; “11. [Updates and Revisions] The Authors agree to keep this OER up to date on terms mutually agreeable to the parties. The Publisher shall have the right to update the OER should the original authors fail to update on a reasonable schedule.”

The flexible nature of OER, especially the ability to reuse and remix content, means that it is important to track versions of your OER. Imagine an instructor downloading your OER at the beginning of the summer, planning their course, and then asking the students to download your OER in the fall, only to find that there have been significant changes. Version control can help prevent that problem, as it informs readers not only when the resource has been updated, but also in what ways it has changed.

Small errors (typos) that don’t change the meaning of the text can be corrected without creating a new version of the text, but anything more significant (such as an update to the text or a new image or corrected quiz question) requires version control and needs to be tracked. Many open textbooks do this in the back of the text—see BCcampus for an example. Will your authors be willing to do the version control? If not, it may be better to handle these issues in-house, if you have the staff.

You should also consider when you plan to make more significant changes or updates. The whole point of version control is so that people know they have the most up-to-date version of the text. You may want to update on a rolling basis or ask faculty to gather the feedback and changes and do these at a specific time each year (e.g., summer).

Sustainability of Programs

The ultimate goal is to create a viable and sustainable program that meets its objective: to create and share freely available reusable resources. Of course, this is just an overview and there are many areas of sustainability that you need to consider, but always keep the end goal in mind.

Wiley (2007) sums up the sustainability issues surrounding OER and offers the following advice:

- Be explicit in your goals and be tenacious about focusing on them. If you do not have goals, you cannot sustain your project or program.

- Decide what type of organization you want to be. Will you be a more centralized, coordinated organization with a specific agenda in mind (e.g., put all of our courses online for free) or will you be more decentralized where the projects are taken on one at a time with no specific end destination?

- Decide which resource types you will offer and what media formats you can support. This may limit the types of projects you can take on and sustain.

- Decide how much support you can provide reusers of your content.

- Find other non-financial incentives for your potential authors or adaptors.

- Keep an eye on your costs and try to reduce them when possible. (Wiley 2007, 19)

Whatever decisions you make about how you will maintain and update the OER, sustainability should be built into your strategic plan. There is no one model of how to do this, so be intentional in your approach.

Conclusion

Sustaining an OER program or project is not an easy task (Wiley 2007). There will always be trade-offs to consider. For example, if your program relies heavily on volunteers, you can save some money, but your resources may be unreliable. Sustainability, like most other aspects of OER, needs to be built into your planning at an early stage. For each project, make a sustainability plan. Build this plan into your MOU or another form of agreement. Take the time to think about project and program sustainability even before you begin.

Recommended Resources

- OER Field Guide for Sustainability Planning: Framework, Information and Resources (Desrochers 2019)

- RLOE Sustainability Guide (Regional Leaders of Open Education, n.d.)

- On the Sustainability of Open Educational Resource Initiatives in Higher Education (Wiley 2007)

- Sustainability can refer to both the longevity and effectiveness of the program and the maintenance and upkeep of an individual project.

- Build a sustainability plan into your project from the beginning. For example, make sure your authors understand that they will need a plan to keep their content current.

- Determine what actions you will take to keep a project up to date (e.g., regular link checking) and what actions the authors need to take (e.g., review for currency, update readings).

- Develop a plan for archiving materials that are no longer being kept up to date.

- Sustainability of a program requires funding and resources. Build sustainability into the strategic plan for your program.

References

Amiel, Tel. 2013. “Identifying Barriers to the Remix of Translated Open Educational Resources.” The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning 14 (1): 126–44. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v14i1.1351.

Annand, David. 2015. “Developing a Sustainable Financial Model in Higher Education for Open Educational Resources.” The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning 16 (5): 1–15. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v16i5.2133.

Derochers, Donna M. 2019. OER Field Guide for Sustainability Planning: Framework, Information and Resources. rpk GROUP. https://oer.suny.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/rpkgroup_SUNY_OER-Field-Guide.pdf.

Downes, Stephen. 2007. “Models for Sustainable Open Educational Resources.” Interdisciplinary Journal of E-Learning and Learning Objects 3 (1): 29–44. Informing Science Institute. https://www.learntechlib.org/p/44796/

Hilton, John III, David Wiley, Jared Stein, and Aaron Johnson. 2010. “The Four R’s of Openness and ALMS Analysis: Frameworks for Open Educational Resources.” Open Learning: The Journal of Open and Distance Learning 25 (1): 37–44. http://hdl.lib.byu.edu/1877/2133

Jacob, Meredith, Peter Jaszi, Prudence S. Adler, and William Cross. 2021. Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for Open Educational Resources. American University Washington College of Law. https://oer.pressbooks.pub/fairuse/

Lashley, Jonathan, Rebel Cummings-Sauls, Andrew B. Bennett, and Brian L. Lindshield. 2017. “Cultivating Textbook Alternatives From the Ground Up: One Public University’s Sustainable Model for Open and Alternative Educational Resource Proliferation.” The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning 18 (4): 212–30. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v18i4.3010

OECD (2007) “Giving Knowledge for Free: The Emergence of Open Educational Resources, Centre for Educational Research and Innovation, Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development” Accessed February 10, 2022. http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/35/7/38654317.pdf

Open Education Network (OEN). n.d. “Adaptable Open Educational Resources Publishing Agreement” Accessed June 14. 2021. https://docs.google.com/document/d/1HHf0GKoSLlNt1IgFurRwZxLiPfoI9NAE16VynhUpXmA/edit

Ovadia, Steven. 2019. “Addressing the Technical Challenges of Open Educational Resources.” portal: Libraries and the Academy 19 (1): 79–93. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2019.0005

Regional Leaders of Open Education. n.d. “RLOE Sustainability Guide.” Accessed July 14, 2021. https://docs.google.com/document/d/1YaJ3BO7BmAn-Dj1V1Gj9SpGeOyNb8ZLFrq0elBd10kw/edit?usp=sharing

Wiley, David. 2007. On the Sustainability of Open Educational Resource Initiatives in Higher Education. Paper Commissioned by the OECD’s Centre for Educational Research and Innovation (CERI). http://www.oecd.org/education/ceri/38645447.pdf

Wiley, David, Linda Williams, Daniel DeMarte and John Hilton. 2016. “The Tidewater Z-Degree and the INTRO model for Sustaining OER Adoption.” Education Policy Analysis Archive, 23(41). https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/2750/275043450060.pdf