A Quick Guide to Open Education

1

Abbey K. Elder

This chapter was adapted from The OER Starter Kit by Abbey K. Elder, licensed CC BY 4.0. The sections on Licensing and Public Domain were adapted from UH OER Training by Billy Meinke, licensed CC BY 4.0.

There are many practices, theories, and tools that you’ll need to learn about to manage an OER program effectively at your institution. However, before broader discussions around pedagogy, innovation, and support structures begin, most institutions start by exploring the idea of utilizing open educational resources (OER) in their courses. To provide a foundation for the discussions surrounding OER throughout the rest of this book, this chapter will introduce the basics, focusing on definitions, foundational components, and open licensing for OER.

What is an Open Educational Resource?

The Scholarly Publishing and Academic Resources Coalition (SPARC) defines OER as:

“teaching, learning, and research resources that are free of cost and access barriers, and which also carry legal permission for open use. Generally, this permission is granted by the use of an open license (for example, Creative Commons licenses) which allows anyone to freely use, adapt, and share the resource—anytime, anywhere.”

This definition has a few key components, but in most contexts, it can be broken down into two major requirements: the freedom for anyone to access a piece of content, and the freedom to adapt that content without needing to contact the copyright holder for permissions.

The Variety of OER

Because the term “teaching, learning, and research resources,” can comprise a wide variety of materials, the OER your instructors utilize may come in many forms. To showcase this diversity, let’s explore the material types available to filter in the popular OER repository, OER Commons:

- Activities & Assignments: labs, homework, and assessments

- Class Guides: syllabi and student guides

- Courseware: lectures, modules, and full courses

- Instructor Materials: lesson plans and teaching strategies

- Mixed Media: illustrations, games, videos, podcasts, simulations, and interactive materials

- Reading Materials: case studies, data sets, lecture notes, primary sources, textbooks, and other readings

Since textbooks are often seen as the ubiquitous “course material” in discussions about the need for free, open content in education, it is no surprise that open textbooks are often seen as the default OER. However, it is important, especially as an OER program manager, to remember that there are a lot of options available for faculty looking to incorporate OER into their courses. Furthermore, thanks to their open nature, OER can be adopted, adapted, or remixed to fit your faculty members’ needs. This may include moving an OER into a new format, like taking a largely text-based OER and adding interactive elements, or making a video out of a set of open lecture slides.

The Freedoms of OER

One of the most popular aspects of an OER is the fact that they are literally free, without a financial cost barring access. OER can be accessed by anyone in the world for free through the Internet, and they can be printed at cost as well.

Because open educational resources are all free to access and share, they have become incredibly powerful tools to support access to knowledge. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the cost of educational books and supplies has risen 1,886% since 1967, nearly triple the rate of inflation for all items in the Consumer Price index, which rose only 676% during the same period of time (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics 2020). With prices rising at an incredible rate, it is no surprise that OER came into popular use in the 2010s.

In addition to this freedom from commercial costs, OER also have clear permissions, or reuse rights, embedded through open licenses.

Wiley (2014) solidified the ideas of freedom for open content by encapsulating it in permissions colloquially known as the 5 Rs:

- Retain: the right to make, own, and control copies of the content (e.g., download, duplicate, store, and manage)

- Reuse: the right to use the content in a wide range of ways (e.g., in a class, in a study group, on a website, in a video)

- Revise: the right to adapt, adjust, modify, or alter the content itself (e.g., translate the content into another language)

- Remix: the right to combine the original or revised content with other material to create something new (e.g., incorporate the content into a mashup)

- Redistribute: the right to share copies of the original content, your revisions, or your remixes with others (e.g., give a copy of the content to a friend).

Each of the five freedoms outlined by Wiley plays an important role in the utility of an open educational resource. For example, without the right to “remix” materials, an instructor who teaches an interdisciplinary course would not be able to combine two disparate OER into a new resource that more closely fits their needs.

OER Definitions

There are many definitions available for OER, and these definitions vary in specificity and length. However, there are some commonalities among these definitions, including four common criteria that are used to determine whether materials should be considered OER:

- Open license required: the item must be available under an open copyright license, through an open source license, Creative Commons license, or through dedication to the public domain.

- Right of access, adaptation, and republication: The open license applied to the item must allow for users to access, adapt, and redistribute copies of the open resource. This can be accomplished by making content available in multiple formats: a work may be available online, provide a downloadable copy for offline reading, and a downloadable version which is editable (i.e., a .DOC file for text or a .AI file for complex images) (Wiley 2014).

- Non-discriminatory: the item can explicitly be reused by “anyone, anywhere,” and not for educational purposes only (or with restrictions on who can access and use the item).

- Does not limit use or form: the item does not include a NonCommercial limitation on its reuse, such as might be done through a Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial license (Creative Commons Wiki Contributors 2020).

A set of definitions from various organizations are provided below. While few definitions include all four criteria, most include the first two: the requirement of an open license and the right for users to access, adapt, and share the work.

- SPARC: “teaching, learning, and research resources that are free of cost and access barriers, and which also carry legal permission for open use. Generally, this permission is granted by use of an open license (for example, Creative Commons licenses) which allows anyone to freely use, adapt and share the resource—anytime, anywhere.” (SPARC, n.d.)

- William and Flora Hewlett Foundation: “we use the term “open education” to encompass the myriad of learning resources, teaching practices and education policies that use the flexibility of OER to provide learners with high quality educational experiences. Creative Commons defines OER as teaching, learning, and research materials that are either (a) in the public domain or (b) licensed in a manner that provides everyone with free and perpetual permission to engage in the 5R activities– retaining, remixing, revising, reusing and redistributing the resources.” (William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, n.d.)

- Cape Town Open Education Declaration: “open educational resources should be freely shared through open licenses which facilitate use, revision, translation, improvement and sharing by anyone. Resources should be published in formats that facilitate both use and editing, and that accommodate a diversity of technical platforms. Whenever possible, they should also be available in formats that are accessible to people with disabilities and people who do not yet have access to the Internet.” (Cape Town Open Education Declaration 2007)

- UNESCO: “teaching, learning and research materials in any medium – digital or otherwise – that reside in the public domain or have been released under an open license that permits no-cost access, use, adaptation and redistribution by others with no or limited restrictions.” (UNESCO, n.d.)

- State of Texas: “a teaching, learning, or research resource that is in the public domain or has been released under an intellectual property license that permits the free use, adaptation, and redistribution of the resource by any person. The term may include full course curricula, course materials, modules, textbooks, media, assessments, software, and any other tools, materials, or techniques, whether digital or otherwise, used to support access to knowledge.” (TEC § 51.451)

Discussions around what should “count” as OER have abounded over the last decade, particularly when it comes to licensing these works. The debate around “how open” an OER should be is addressed very well in Jhangiani’s (2017) article, Pragmatism vs Idealism and the Identity Crisis of OER Advocacy:

“Despite its merits, it would be naïve to believe that adopting an integrated approach would eradicate all tension within the OE movement. Idealists may still insist that OER creators apply CC licenses that meet the definition of “free cultural works” (Freedom Defined 2015). Pragmatists, on the other hand, will acknowledge that OER creators may have reasonable grounds for attaching a Noncommercial (NC) or even a NoDerivatives (ND) clause, even though an Attribution-only license (CC BY) facilitates the maximum impact and reuse of OER… Although these tensions will not disappear overnight, I believe it essential that we recognize both drives and have a deliberate, nuanced conversation about how to flexibly harness both idealism and pragmatism in service of the goals of the OE movement.” (para. 24)

Thinking about what aspects of OER are the most important to emphasize at your institution is a vital step for those starting an OER program. Choosing or creating a definition for OER can color the rest of your initiative. Consider alterations that anchor your OER program’s work to your institution’s goals, missions, or values. This can be achieved by adding a vision or mission statement alongside your OER program’s outreach materials, and tying that vision to both your chosen definition and your institution’s mission.

Do not attempt to redefine OER by committee. As we’ve shown above, there are enough definitions to choose from already. Rather than starting from scratch on an institutional definition, consider adopting an existing definition of OER, or rephrasing an existing definition for clarity. When taking the idea of an official definition to your team or administration, bring examples based on the sort of definition you would like to support.

Copyright and Open Licensing

Since permissions and reuse rights are an integral part of OER, as an OER program manager, you will need to have a basic understanding of copyright law, particularly as it pertains to open licenses. Having a basic understanding of copyright law can help you feel more confident when answering questions from faculty about what makes an OER different from a traditional educational resource besides the fact that they are available at no cost. In addition, having this knowledge can help when managing OER projects that involve remixing multiple resources into something new. Since not all open licenses can be combined with one another, understanding how open licenses work can help you make more informed decisions about how to combine remixed works efficiently.

Since the authors of this book are primarily situated in the United States, the main examples used here will be referring to the standards within U.S. copyright law. The specific rules and regulations around licensing, fair use, and intellectual property in your country may differ from the ones described here, and you should seek out counsel on best practices in your own community. If you know of any resources we could add to this section to help readers locate applicable copyright guidance for their own contexts, please let us know by using the Contact Form in the front matter of this book.

If you have a team that oversees OER work, you can delegate more complex copyright questions to your institutional copyright office or whichever team member has the most experience with this work; however, everyone who works with OER should have a baseline understanding of fair use and open licenses to help you answer questions from faculty. Keep in mind that if you do not have a law degree or a lawyer on your team, you will want to have an external contact who does have this background to help you answer more complex copyright concerns from faculty.

U.S. Copyright Law

U.S. copyright law protects an author’s rights over their original creative works, such as research articles, books and manuscripts, artwork, video and audio recordings, musical compositions, architectural designs, video games, and unpublished creative works (17 USC §102). As soon as something is “fixed in a tangible medium of expression,” it is automatically protected by copyright. A resource is considered fixed when:

“its embodiment …by or under the authority of the author, is sufficiently permanent or stable to permit it to be perceived, reproduced, or otherwise communicated for a period of more than transitory duration.” (Legal Information Institute, n.d.)

In other words, an idea for a book is not protected by copyright, but the first draft of a manuscript is. Copyright protection ensures that the creator of a work has complete control over how their work is reproduced, distributed, performed, displayed, and adapted (17 USC §106). The faculty you work with will not need to register a resource with the U.S. Copyright Office for this to come into effect; it is automatic.

Licensing

The copyright status of a work determines what you can and cannot do with it. Most copyrighted works are under full, “all rights reserved” copyright. This means that they cannot be reused in any way without permission from the work’s rightsholder. This is usually the creator of the work, but it may also be the publisher of the work, for published scholarly materials like books and articles.

If you are supporting an author who wants to get permission to reuse someone else’s work or who has created a work that others want to reuse, this can be handled through the use of a license. A license is a statement or contract that allows you to perform, display, reproduce, or adapt a copyrighted work in the circumstances specified within the license. For example, the copyright holder for a popular book might sign a license to provide a movie studio with one-time rights to use their characters in a film.

If an OER is available under a copyright license that restricts certain reuses, or if an author does not want to license out their work for reuse, you can help faculty make a fair use assessment for reproducing or adapting that work. Some best practices you can follow when considering this approach have been compiled in the Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for Open Educational Resources (Jacob, Jaszi, Adler, and Cross 2021).

Open Licenses

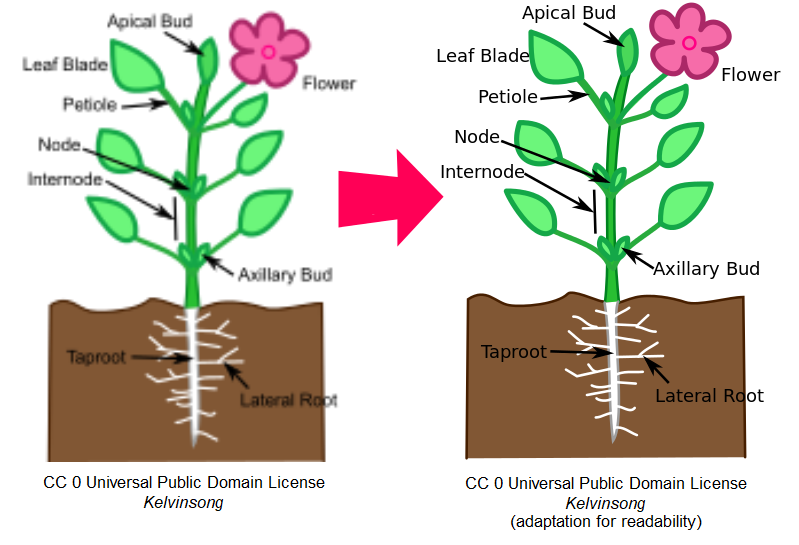

In contrast to all rights reserved materials, OER facilitate downstream reuses through the application of open licenses, copyright licenses that allow anyone to exercise the rights allowed under the license, not just a single user with permissions from the rightsholder. These explicit reuse permissions make OER not just free to access, but also free for instructors who want to alter the materials for use in their course. For example, in Figure 1.2 below, an openly licensed image has been traced to make it more readable.

Adaptations that improve the clarity of a work are a great way to leverage an open license through small edits rather than more complex changes. Showcasing examples like the one in Figure 1.2 may be useful for helping instructors who are uncertain how smaller contributions and adaptations can improve a work that is almost perfect for their course.

Creative Commons Licenses

The most popular open licenses for OER are Creative Commons (CC) licenses, standardized licenses that allow users to reuse, adapt, and re-publish content with few or no restrictions.The six Creative Commons licenses include combinations of one or more of the following components:

- Attribution (BY): Proper attribution must be given to the original creator of the work whenever a portion of their work is reused or adapted. This includes a link to the original work, information about the author, and information about the original work’s license.

- Share Alike (SA): Iterations of the original work must be made available under the same license terms as the original work.

- Non-Commercial (NC): The work cannot be sold at a profit or used for commercial means. Copies of the work can be purchased in print and given away or sold at cost.

- No Derivatives (ND): The work cannot be edited or remixed. Only identical copies of the work can be redistributed without additional permission from the creator.

Under the description for the No Derivatives license, we noted that users can get permission from a creator for additional rights not traditionally allowed under the license. CC licenses may allow specific reuses up front, but they also work within traditional copyright law, and can be amended for individual reuses through additional permissions from the rightsholder. For example, if you are working with an instructor who wants to adapt a work that is available under an Attribution ShareAlike license by remixing it with a work under a more or less restrictive license, your author can ask the original work’s creator for permission to reuse that work in a differently-licensed context. If the original creator says no in this case, your author might seek out an alternative work, or consider reusing a portion of that ShareAlike licensed work under fair use.

Attribution

Although there are different rules for each license, every CC license includes the BY (Attribution) component, which requires that users provide proper credit for any original work being shared or adapted. Attribution is a similar process to citing for academic works, but there are some key differences. For example, attribution is a legal requirement of reusing licensed content, whereas citations are an ethical, academic requirement when referring to a peer’s work. Instructors you work with can cite openly licensed content in their OER if they are simply referring back to the content within the work, just as they would for an all rights reserved resource, but if they are sharing, editing, or remixing a resource, that will require attribution. An attribution should include four parts: the item’s title, author, license, and a link to its original source. This is often referred to with an acronym, such as “TALS.”

Attribution Example

Let’s explore an example of attribution in action. An instructor you are supporting finds this song and wants to incorporate it into their OER project: “First Results.” Sometimes, attribution statements are created and presented alongside an OER to make them easier for users to attribute correctly. When this is not the case, you simply need to locate all four pieces of the “TALS” formula to create an attribution statement for the work you are reusing. When visiting this song’s website, you can find that the creator is “Blue Dot Sessions” and that the work is titled “First Results.” That gets you two pieces of TALS already: the title and author of the work.

Next, you need to locate the license. This is often in one of three places: the footer, the “about” page, or the homepage of the website on which the work is housed. In our example, the license is prominently placed in the details on the right side of the song’s webpage: a Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial license.

Now that you have all those pieces in place, be sure to copy the links to both the resource’s website and its license information, as these make up the more robust pieces of the source and license portions of your attribution.

Once you have your title, author, license, and source, you can compile this information in an attribution statement:

The music used in this work is “First Results” by Blue Dot Sessions, available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

If there is no license applied to a work, that means the resource is likely under all rights reserved copyright. If you cannot find the license clearly marked on the website where the work is hosted, consider searching your web search engine of choice (i.e. Duck Duck Go or Google) for the name of the work and “Creative Commons.” If that brings back no results, you can contact the creator of the work for context.

For additional support creating an attribution statement, you can point faculty toward the Open Washington Attribution Builder, though I recommend reviewing the basics with authors as well, to ensure that they understand the importance of including robust attribution information for any openly licensed works they reuse.

Implementing a CC License

Creative Commons has an online Marking Guide that demonstrates how to mark CC license on different types of media (Creative Commons Wiki contributors 2019). Making a license obvious is an important part of the dissemination process for OER, as it ensures that others can recognize that the work is openly licensed and feel comfortable reusing the work. No matter the format, there are three standards faculty implementing a CC license should follow:

- Make it clear

- Make it visible

- Provide links (to the license and the work)

Here is a book-level license that encapsulates the entire work while noting that not all content may be available under the same license:

“Except where otherwise noted, this work is copyrighted by [AUTHOR] and available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) license. You are free to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format. However, you must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use.

Items available under a different license or used under the Fair Use doctrine (17 U.S.C. § 107) are marked in the text. Adopters in a non-U.S. jurisdiction should rely on the appropriate quotation provisions of their own national copyright laws.

We suggest the following citation: [CITATION EXAMPLE]”

As an alternative, let’s look at how you might implement an open license on a video. The language will be similar, but its application needs to be different to accommodate the different mode of communication. For example, let’s look at this video I created in 2018:

There are three ways the license for this video has been marked:

- The Creative Commons Attribution License option was selected within the YouTube interface when posting the video, so it would show up when users filter by license.

- Within the description of the video, a statement was added about the license:

“Open Education: Learning the Ropes” by Abbey Elder is available under a Creative Commons 4.0 License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/” - A Creative Commons Attribution icon was added within the video.

This third point is particularly important since videos are often shared outside of the context of their platform, where the description and metadata cannot be consulted. I would even recommend that those putting out video or audio content verbalize the CC license applied either at the beginning or end of the work to make the license clear for end users.

Talking about Licensing

There are a few situations when you’ll likely need to talk to faculty about open licenses. These include:

- When adopting an OER, the instructor needs to understand the reuse rights for that work if they want to create print copies or share a copy of a work with their class (or peers) online.

- When adapting or remixing OER, the instructor needs to navigate which CC licenses are compatible with one another and how to properly attribute each work they use.

- When choosing a license for their own work, instructors need to understand the pros and cons of each CC license so they can make an informed decision about how to license their work.

In the following section, we will be primarily discussing the second and third points on that list.

Helping Instructors Choose a License

As the OER program manager for your institution, you may be asked to help faculty choose a license to apply to their OER projects. The first thing you will need to do is to assess the OER project itself and whether the materials created and/or adapted will affect the license the faculty member can choose.

Below are some questions you should ask faculty at this stage:

- How familiar are they with CC licenses?

- Is the bulk of their work original, or remixed selections from other sources?

- Are they adapting a single work, or pulling together multiple OER into a larger remix project?

- Are they planning to use any material under all rights reserved copyright within their work, and why?

- Are they citing and referring to other works, or incorporating these other works into their project directly?

Each of these questions will help you have a more productive conversation. For example, if the faculty member is not familiar with CC licenses, you will want to start by explaining each license and how they work. In the following section, we explore a few scenarios you may encounter when supporting faculty licensing and organizing attributions for more complex OER remix projects.

Licensing and Attribution for Remix Projects

If you’re working with a faculty member on an adaptation or remix project which includes multiple components, attribution may be a more complex process. Below, we have outlined a few common examples you can review.

Creating a New Work with Adapted Figures

Let’s say you are working with a creator who has developed an OER with the addition of some extra open content, such as background music within a video or images within a set of slides. In these situations, the author should credit themselves as the OER’s creator and provide item-level attributions for the adapted works included within their project. In Figure 1.3, a slide using an openly licensed image includes attribution information just under the image, but this attribution could also be placed in the notes section of the slide, or in a description for other types of works.

Adapting a Single Existing Work

If you are supporting a faculty member who is adapting a single work for use in their course, they should provide attribution for the original work’s authors, and list them as the creators for the work. If they have contributed original content to the work, your faculty member may add their name to the Contributors or Authors list. As a best practice, the individual adapting the content should also provide a description outlining the changes they have made to the original work and any additions they have contributed.

Remixing a Single Existing Work, with Additions

If the individual you are supporting is adapting a single work while adding selections from other openly licensed works, they should follow the instructions from our previous example, and provide attribution for the additional adapted content within the sections containing them.

Alternatively, the faculty member may choose to provide a list of all the adapted content making up their work in a single list. For books, this might be placed in the front matter, while for other OER projects, this might be placed in a footer, notes field, or description section.

Remixing Two or More Works with Different Licenses

Finally, if the faculty member you are supporting has remixed a set of OER with different licenses, they will need to carefully choose the final license of their remixed work. As an OER program manager, you will need to discuss how to choose a license for the new OER that is compatible with each of the remixed works’ original licenses. As Table 1 shows, most licenses used for OER are compatible with one another, with a few notable exceptions.

| License | Public domain mark | CC BY | CC BY-SA | CC BY-NC CC BY-NC-SA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public domain mark | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| CC BY | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| CC BY-SA | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| CC BY-NC CC BY-NC-SA |

Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

When remixing open content, the CC licenses to be most aware of are ShareAlike licenses, since the two ShareAlike licenses, CC BY SA and CC BY NC SA, are not compatible with one another. This is because an adaptation containing a CC BY SA work must utilize the same license, just as a work utilizing CC BY NC SA materials as its base must utilize a CC BY NC SA license. You cannot apply a more or less strict license to either of these types, so they cannot override one another or be replaced by another license.

If all the OER being utilized by your faculty member have compatible licenses except for one, you might consider offering to help locate an alternative resource for the faculty member to integrate into their project, or asking for additional permissions from the work’s creator. As an alternative compromise, you can suggest that the creator apply an overarching license to their work, and note that pieces of the work are available under separate licenses. Noting that a work contains resources that are used under a separate license can be done through standard language, such as “This work is available under a Creative Commons NonCommercial License, except where otherwise stated.” This is the same language you might use if one of the images used in a resource was utilized under fair use or with permission from the rightsholder, for example.

Tips for Talking to Faculty

Regardless of the situation you find yourself in, when helping an instructor choose a license for their OER project, remember these three tips: keep the creator on your side, don’t trivialize their concerns, and remind them that open licenses are powerful tools for both creators and users.

Keep the Creator on Your Side

As you discuss open licensing, it’s important to ensure that faculty creators are comfortable and confident in their decisions. Early on, discuss each of the open license options available with the faculty member, and help them come to a decision on which license will be best for their project.

The Creative Commons Choose a License tool can help faculty navigate this process if you cannot meet with them in person, but the choose a license tool is simple and you should explain the licenses to authors in clear, concise language before they use the tool themselves.

Don’t Trivialize the Creator’s Concerns

Faculty new to OER, and even veterans in the space, may be hesitant to apply a CC BY license to their work, fearing that future users may create an adaptation that is inaccurate, unorganized, or even slanderous. As a program manager, it is best not to disregard these concerns or to argue that they are unfounded. Instead, make sure that authors understand that they can ask to have their name removed from any adaptations that they do not approve of, and that the version of their work that they create will always be available in the form they have published. Any adaptations created by other users will be hosted on other platforms, or clearly marked as adaptations with a link to the original work.

After you address the faculty members’ concerns, then you can then follow up with information about how negative adaptations of OER are rarely an issue, and showcase examples of positive adaptations that have occurred over time. Talking about the positive outcomes of open licensing can help faculty move past any anxiety they may feel regarding openly licensing their work, and ensure that all the contributors working on a project are comfortable with the level of openness they are moving toward.

Remind the Creator that Licenses Help Everyone

OER are useful not in spite of but because they can be used by anyone and adapted for various purposes. However, that can be hard to explain when a creator is thinking about a specific use case for their own works, particularly if they are protective of their copyright. To help faculty conceptualize how adaptations can improve and build on their work, share examples of different types of adaptations that have been done by creators at other institutions already. For example, a future user might:

- translate an open textbook into another language,

- add institutionally-relevant examples to a video,

- expand on a set of slides by adding “concept questions” at the end,

- remove sections of a work that aren’t taught at their institution, or

- change the focus of a work to support a more focused course (e.g., adapting “Algebra” to support “Algebra for Forestry Students”).

Finally, remind faculty that their version of their work will always be theirs, and that–if they wish– the creator can integrate adaptations that others have created into a future version of their work, or even collaborate with faculty at other institutions who have adapted their work to create more OER in the future. There are many opportunities to do more exciting and innovative work with OER, and highlighting those possibilities can help faculty feel more comfortable about making their work open.

The CC BY license is often the preferred choice for OER projects because it allows the most freedom for users when adapting and remixing content. However, except the No Derivatives license, all CC licenses meet the standards for OER. While it may be tempting to promote the use of the most open license for all the OER projects at your institution, program managers should strive to promote faculty freedom in choosing the license that is right for their needs, so long as it meets the 5 R rights required for their content to be considered an OER.

Content in the Public Domain

Works that are no longer protected by copyright are considered part of the public domain. Items in the public domain can be reused freely for any purpose by anyone, without giving attribution to the author or creator. Public domain works in the U.S. include works whose creator died 70 years prior, works published before 1926, or works dedicated to the public domain by their rightsholder. The Creative Commons organization created a legal tool called CC 0 to help creators dedicate their work to the public domain by releasing all rights to it (Peters 2010).

What Isn’t an OER?

Misconceptions about their usefulness and availability of OER have abounded among some instructors (Seaman and Seaman 2018). After all, an OER may come in the form of a textbook, lesson plan, syllabus, reading list, or even a piece of educational software. Rather than trying to define OER as a single item or implying that “open textbooks” are the main form of OER, it may be better to talk about what isn’t an OER.

Anything that isn’t both free and open with 5 R permissions is not an OER. For example, library-licensed ebooks may be free for students to access, but there is a cost incurred by the institution for their purchase and they certainly aren’t openly licensed. Similarly, most websites and online materials like images or videos are free to access but are not openly licensed. Because these materials do not meet the definition for open educational resources, you should not call them OER.

However, supporting OER at your institution does not have to be an all-or-nothing proposition. There are a lot of high quality educational materials available for free online or through your institution’s library that are not openly licensed. If you know where the materials came from and how to use them, feel free to share links to these materials as no-cost options for an instructor’s course. So long as you don’t conflate them with OER and you do not advocate for their adaptation as OER without a fair use assessment or permission from the author, this is a perfectly fine choice.

Conclusion

Understanding OER is a core component of an OER program manager’s duties. These resources can come in a wide variety of sizes and formats, but at their core they have two main components: they are free for anyone in the world to access online and they are available under an open license which allows for their reuse and adaptation. Anyone can talk about OER by focusing on these two concepts, and it is often best to begin discussions with faculty at a basic level. It takes time to comprehend and explain the smaller components of an OER, such as licensing and attribution. This chapter has reviewed copyright for OER in some depth, but we recommend that program managers seek support from copyright experts at their institution or review additional materials if they wish to explore copyright and licensing in more detail.

Recommended Resources

- Can I use this? Copyright Decision Path (Harper College, n.d.)

- Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for Open Educational Resources (Jacob, Jaszi, Adler, and Cross 2021)

- Creative Commons Certificate for Educators, Academic Librarians and GLAM (Creative Commons 2020)

- Why OER? (Council of Chief State School Officers 2016)

- Open educational resources come in many formats and types, and because of this they can be seen both as “flexible, powerful tools” and “amorphous, difficult to explain materials.” Being able to discuss this variety in a positive and straightforward manner is key for program managers who want to support the growth of a new OER program.

- Because misconceptions about OER are still prevalent among faculty new to OER, you should have a clear definition of OER in use at your institution and be able to communicate what this definition means for those new to OER.

- Creative Commons licenses are the most common and simplest open licenses to apply to OER, and every CC license except those using the No Derivatives provision are sufficient for use on open educational resources.

- If you find you cannot support a course with OER currently available, do not despair! New OER are being developed every year, and in the meantime, you can support instructors by offering alternatives, like library licensed ebooks or courseware available at a lower cost than your faculty members’ current course materials.

References

Cape Town Open Education Declaration. 2007. “Read the Declaration.” Accessed January 30, 2022. https://www.capetowndeclaration.org/read/

Council of Chief State School Officers. 2016, December 14. “Why OER?” YouTube video, 3:48. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qc2ovlU9Ndk

Creative Commons. 2020. “Creative Commons Certificate for Educators, Academic Librarians and GLAM.” https://certificates.creativecommons.org/cccertedu/

Creative Commons Wiki contributors. 2019. “Marking Your Work with a CC License.” https://wiki.creativecommons.org/wiki/Marking_your_work_with_a_CC_license

Creative Commons Wiki Contributors. 2020. “What are Open Educational Resources (OER)?” https://wiki.creativecommons.org/wiki/What_is_OER%3F

Free Software Foundation. n.d. “What is copyleft?” https://www.gnu.org/copyleft/copyleft.html

Harper College. n.d. “Can I Use This? Copyright Decision Path.” Accessed January 30, 2022. https://sites.google.com/view/harper-copyright-tutorial/can-i-use-this?

William and Flora Hewlett Foundation. n.d. “Open Education.” Accessed February 2, 2022. https://hewlett.org/strategy/open-education/

Jacob, Meredith, Peter Jaszi, Prudence S. Adler, and William Cross. 2021. Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for Open Educational Resources. American University Washington College of Law. https://oer.pressbooks.pub/fairuse/

Jhangiani, Rajiv. 2017. “Pragmatism vs Idealism and the Identity Crisis of OER Advocacy.” Open Praxis 9 (2): 141-150. https://openpraxis.org/index.php/OpenPraxis/article/view/569/322

Legal Information Institute. n.d. “Fixed in a Tangible Medium of Expression.” In Wex Legal Dictionary. https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/fixed_in_a_tangible_medium_of_expression

Peters, Diane. 2010. “Improving Access to the Public Domain: The Public Domain Mark.” Creative Commons Blog. https://creativecommons.org/2010/10/11/improving-access-to-the-public-domain-the-public-domain-mark/

Seaman, Julia E., and Jeff Seaman. 2018. “Freeing the Textbook: Educational Resources in U.S. Higher Education, 2018.” Babson Survey Research Group. https://www.onlinelearningsurvey.com/reports/freeingthetextbook2018.pdf

SPARC. n.d. “Open Education.” Accessed January 30, 2022. https://sparcopen.org/open-education/

Texas Education Code. TEC § 51.451, Definitions. https://texas.public.law/statutes/tex._educ._code_section_51.451

UNESCO. n.d. “Open Educational Resources (OER).” Accessed January 30, 2022. https://en.unesco.org/themes/building-knowledge-societies/oer

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Data Viewer. 2020. Educational books and supplies. https://beta.bls.gov/dataViewer/view/timeseries/CUSR0000SEEA;jsessionid=8F79D40725E5DD39597F15CC40A1AD0C

U.S. Copyright Office. Copyright Law of the United States, 17 USC §102. https://www.copyright.gov/title17/92chap1.html#102

U.S. Copyright Office. Copyright Law of the United States, 17 USC §106. https://www.copyright.gov/title17/92chap1.html#106

Wiley, David. 2014. “Defining the ‘Open’ in Open Content and Open Educational Resources.” opencontent.org. Accessed January 30, 2022. http://opencontent.org/definition/