1 Chapter 1

Early Life

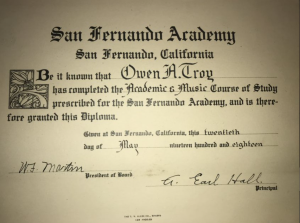

Dr. Owen A. Troy Sr. was born on November 3rd, 1899 to parents Theodore Wellington Troy and Estella Juliet Washington. An era of rapid change in the United States, this young African American scholar contended with a developing racial envir

onment resulting in challenges in access to education and employment, and an evolving Seventh-day Adventist Church. The Troy family brought to the Seventh-day Adventist Church one of its greatest scholars, a man who revolutionized pastorship, trailblazed the pathway to higher education, and helped mark the African American contribution to the church through his leadership roles.

Beginning life in the city of Los Angeles, California was far from insignificant. California, by the 1900s, was bustling with diversity. A mix of Mexican and American inhabitants, infused with waves of immigrants landing on the western shores as well as those who travelled overland west, the city rapidly grew in both size and enterprise. Theodore and Estella Troy were two of over 12,000 African Americans who settled in the urban areas of San Francisco, Los Angeles and Oakland by 1910, in what is termed the Great Migration. The state of California’s African American population increased by over 525% between 1860 and 1910, representing a rapidly developing community amongst the three principal urban centers.[1] Despite San Francisco holding the reputation as the “most cosmopolitan and sophisticated African American community in the West,” it was the Troy’s own city, Los Angeles, that had the largest African American population.[2]

Little is known about Theodore and Estella Troy, except that they attended Tougaloo College in Mississippi and moved to Los Angeles where Theodore became the city’s first Black postman.[3] It is likely that the couple were Protestants prior to their transfer West, since Tougaloo College in Jackson, Mississippi was founded in 1869 by the American Missionary Association of New York. Intended to provide education for former slaves, the missionaries received funding from the Freedmen’s Bureau to established over five hundred schools across the South.[4] Tougaloo College focused on producing teachers to combat illiteracy rates amongst African Americans and operated out of an elaborate, former plantation.[5] After moving to California, the couple purchased land from an Irish farmer, James Furlong, for $750.[6] Located near Vernon, in Los Angeles, their small plot of land was amongst a neighborhood of two hundred other emerging homes, all owned by African American families as a result of the city’s redlining restrictions.[7] Consequently, as one of the only districts in Los Angeles open for Black purchase, the community grew rapidly and attracted a business-minded, wealthy population.[8]

For the young Owen Troy Sr. growing up in, what Chandler Owen of The Messenger called, a “veritable little Harlem in Los Angeles,” the close-knit African American community was a defining force in his personal growth.[9] By the age of eleven, Troy could attend Furlong Tract’s first community school and enjoy the neighborhood’s Black-owned ice cream parlor, while his parents shopped at the community grocery stores, pharmacy, or worked in Furlong Tract’s business district.[10] Furlong Tract also had a flourishing religious community whose welcome to new residents undoubtedly impacted the neighborhood’s success. This influence began for the Troy’s in 1906, when Jennie Ireland and friend Sarah Cain of the Los Angeles Central Church approached Cain’s postman, Theodore Troy, about holding Bible studies at the family home.[11] Jennie Ireland (a white woman) was a prominent SDA leader in California by 1906, having cofounded a self-supporting healthcare ministry for Los Angeles’ residents in 1896. She focused her community work on healthcare, education, and healthy eating, before heading a new path into Bible study at the Troy household. According to one biographer, Jim Wibberding, Ireland felt a close connection to the Troy’s neighborhood, having watched the land transform on her daily railroad commute, “the scene stirred her heart.”[12] Despite being a relatively obscure denomination at the time in California, the Seventh-day Adventist church appealed to Theodore, Estella and their neighbors for a variety of reasons. According to historian Douglas Morgan, “high-achieving, well-educated African Americans dedicated to racial advancement found Adventism, despite its obscurity, to be an appealing path toward that goal” for three main reasons: firstly, the church may have appealed because of its interracial congregations, having formed its first, albeit defeated, inclusive congregation in Washington D.C. ten years before Troy’s birth.[13] With the church’s emphasis on health and education for oppressed peoples, African American new arrivals in Los Angeles benefitted immensely from the health services and education offered by SDA classes, like Ireland’s. What’s more, the church preached vital teachings on truth, redemption, gave direction, and used racially transgressive language.[14] As historian Delbert W. Baker summarized, “Christianity offered general help for the recently freed slave but SDA teachings had the specific system of truth needed.”[15]

Historians Lawrence Brooks De. Graaf, Kevin Mulroy, and Qunitard Taylor in Seeking El Dorado, observed the importance of churches in the development of Californian African American community in the early twentieth century, with historian Shirley Moore emphasizing the roles of women in church organizations.[16] By 1906, California boasted sixty-three African American churches, including places like the Azusa Street Revival in 1906 experimenting in integration, however no Seventh-day Adventist churches yet existed.[17] From the Troy household’s Bible study classes led by Ireland and Cain, formed the Furlong Church in 1908 as the first Black church west of the Mississippi River.[18] With 23 members by August that year, the congregation gained official recognition from the General Conference and moved to their own church building where Ireland continued to mentor church leaders and help community members for six years.[19] Known as the “little mother” of Furlong Tract Church, Ireland mentored a number of prominent individuals including Dr. Ruth Janetta Temple. Temple’s mother assisted with the Bible study classes at Furlong and so Ruth, only seven years older than Owen Troy, was inspired by Ireland’s stories of the health sanatorium at Battle Creek to become a “lady doctor.” Thanks to Theodore and Estella Troy’s financial support, Temple attended the College of Medical Evangelists (now Loma Linda University) in California to become the first licensed Black female physician in the state of California.[20]

Two years before Troy’s birth, the Oakland Home for Aged and Infirm Colored People formed alongside a wave of similar initiatives resulting from the nationwide African American woman’s movement, marking Los Angeles as the center of colored women’s philanthropy and organization by the time Troy turned 13.[21] Cain and Jennie Ireland’s teaching from the Troy household showed the women’s movements’ influence within the SDA community in California since, for Cain and Ireland, undoubtedly the greatest inspiration for teaching the community of Los Angeles stemmed from their religion. Ireland mirrored the preaching of Joseph Bates and E. G. White because alongside Bible studies, Ireland also taught healthy living, home nursing and instructions on cooking. Bates, a founding member of the church, a leading example of the benefits of healthy living as a key teaching, especially for vegetarianism and a greater diet of nuts and seeds. When Seventh-day Adventism reached California in 1868, Ellen White began to emphasize healthy living as an essential component of the SDA message and promoted church-operated agricultural farms, like Platt Valley in California, by the end of the century. [22] E. G. White combined the healthy living idea to the community, advocated for local shops and restaurants to serve healthier meals, as well as ran community classes, like those of Cain and Ireland, for the Seventh-day Adventist congregation. It was through this exposure to religion and humanitarianism that the young Troy began to forge his unique approach to pastorship that would define his legacy.

[1] Lawrence Brooks De Graaf, Kevin Mulroy, and Quintard Taylor (eds.), Seeking El Dorado: African Americans in California (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2001): 14.

[2] Ibid.: 16-18.

[3] On Theodore Troy, see “L.A.’s First Negro Postman Dies at 89,” Los Angeles Tribune, April 3, 1958, 177.

[4] Clarice Thompson Campbell, “History of Tougaloo College,” Dissertation: The University of Mississippi, 1970. Order No. 7016392: 5.

[5] Ibid.: 39-41.

[6] “Furlong Tract Community – L.A.’s First African American Community,” Los Angeles Almanac, 2 Jan. 2019, 1998-2019 Given Place Media, publishing as Los Angeles Almanac. https://www.laalmanac.com/history/hi742.php.

[7] “The Furlong Tract Community (Los Angeles), a story,” AAREG, 21 February 1905, https://aaregistry.org/story/the-furlong-tract-community-in-los-angeles/.

[8] Los Angeles Almanac, “Furlong Tract Community – L.A.’s First African American Community.”

[9] Brooks De Graaf, Mulroy, and Taylor, 21-22.

[10] Los Angeles Almanac, “Furlong Tract Community – L.A.’s First African American Community.”

[11] Sydney Freeman, Jr., and Chloe O’Neill, “Troy, Owen Austin, Sr. (1899-1962),” Encyclopedia of Seventh-day Adventists, 29 January 2020, https://encyclopedia.adventist.org/article?id=8CFZ&highlight=owen|troy.

[12] Jim Wibberding, “Ireland, Jennie L. (1871-1961),” Encyclopedia of Seventh-day Adventists, 3 January 2023 https://encyclopedia.adventist.org/article?id=D9JU&highlight=jennie|ireland.

[13] Morgan, “1919 And The Rise of Black Adventism.”

[14] Barker, “Black Seventh-day Adventists And The Influence Of Ellen G. White.”

[15] Delbert W. Baker, “The Appeal of SDA Teachings to the Freed Slave,” in Delbert W. Baker (ed.), Telling The Story, An Anthology on the Development of the Black SDA Work (Atlanta, Georgia: Black Caucus of SDA Administrators, 1996): 5/22.

[16] Brooks De Graaf, Mulroy, and Taylor; Shirley Moore, essay, ”’Your Life Is Really Not Just Your Own’: African American Women in Twentieth-Century California” in Ibid.: 21.

[17] Ibid.: 21.

[18] Baker, “Timeline of Black Adventist History 1900-1945.”

[19] Jim Wibberding, “Ireland, Jennie L. (1871-1961).”

[20] Denis Kaiser, “Being a Living Letter,” Lake Union Herald, Digital Commons at Andrews University, April 2023, https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2097&context=luh-pubs.

[21] Brooks De Graaf, Mulroy, and Taylor, 112-118.

[22] J. C. Haussler, “The History Of The Seventh-Day Adventist Church In California,” Dissertation: University of Southern California, 1945. Order No. Dp28665: 119-174.