2 Chapter 2

A prominent aspect of Dr. Troy’s legacy is his achievements in education. Dr. Troy is considered the first member of the SDA church to receive a doctorate in Theology, as well as one of the first African Americans to receive a degree in Theology from the University of Southern California, and the second to receive a master’s in religious education from the University of Chicago.

As such, Troy is considered among one of the most significant Seventh-day Adventist scholars in the twentieth century. His first exposure to biblical education began in the Biblical Study classes of Jennie Ireland within his own Los Angeles household, and he would take these teachings with him on his educational journey to countless prestigious institutions.

The first of these institutions was the San Fernando Academy in California. As a Seventh-day Adventist school, Troy had the opportunity to deepen his study of religion from the foundations laid by Ireland’s classes in his childhood home. In a letter of May 15th, 1903, E. G. White summarized the basis for Troy’s experience at the institute: “Let the San Fernando school be conducted along the lines of the ancient schools of the prophets, the Word of God lying at the foundation of all. It is Important that we should have such a school as the one soon to open at Fernando. … We have but few missionaries. From home and abroad are coming urgent calls for workers.”[1]

The school reflected widespread debate in the nation concerning the role of education. For African American new arrivals to the city, Los Angeles provided attractive opportunities to better educate their children. Since the majority escaped from the South in the Great Migration, African American families looked to California’s integrated education system as a fairer system that could equate their children’s education with that of whites’.[2] In relating to wider debates between Booker T. Washington’s program at the Tuskegee Institute, with its industrial education system that favored practical training over academic subjects, E. G. White’s vision for the San Fernando Academy more closely followed the counter approach proposed by the likes of Mary McLeod Bethune, and W. E. B. DuBois in his essay “Pragmatic Black Consciousness.”[3] Since the 1880s, progressive education initiatives extended the standard agricultural and industrial skills to intellectual achievement because, as many including Josephine Silone Yates explained, “Is not our lack of thought, and of the power to think clearly and logically, the fruitful source of nine-tenths of our woes?”[4][3] In comparison, whilst Black enlightenment thinkers, including Alexander Crummell, worried that “intelligent labor… robs its pupils of their natural independence, makes them feel that something distant, foreign and mysterious is better and higher than what is familiar and close at hand,” others argued that Booker T. Washington’s education system as a “way of appeasing whites who felt that blacks should be manual laborers and not strive for high intellectual achievement.”[5] E. G. White, at the turn of the century, applied this emerging philosophy to the education of Seventh-day Adventist students. At San Fernando, for example, the administration combined practical labor with intellectual studies, offering a range of manual skills classes alongside Latin, Advanced Algebra and Botany.

The young Owen Troy’s educational experience was therefore a product of new thinking, both in African American spheres as well as the church. For Ellen G. White, “[n]othing is of greater importance than the education of our children and youth. The church should arouse, and manifest a deep interest in this work; for now as never before.” The academy’s founding in 1901 was not only a product of this national debate amongst African American leaders, but further fueled by debates within the church that sought to overcome prior rules that limited educational ladder of its congregation.[6] Troy’s education is testament to this change; at San Fernando Academy until 1918 he studied religion rather than agriculture, and then continued to push the SDA boundaries of education, going further than a Bachelor’s to achieve what is believed to be the first doctorate in Theology for the church in 1952.

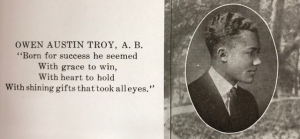

At the Pacific Union College in his teenage years, Troy actively participated in many societies, including the Philmelodic Club, the Glee Club, and one of a few African American students in his graduation class.

He was editor of the Mountain Echo, a school musical newsletter in which he shared his own compositions and wrote frequent passages on the subject.

Troy graduated as the second African American of Pacific Union College

just six years after Frank L. Peterson, the future Negro Department secretary and author of Hope of the Race (1930)’s graduation in 1916. The college’s theological course launched him into further education, as his graduation quote explained: “Born with success he seemed…,” and Troy would return to this college in the future as a visiting professor.

[1] Haussler, “The History of the Seventh-Day Adventist Church in California”: 201.

[2] James Levy, “Forging African American Minds: Black Pragmatism, “intelligent Labor,” and a New Look at Industrial Education, 1879-1900,” American Nineteenth Century History, 17.1 (2016): 43-73: 137.

[3] Ibid.

[4]Ibid., 57.

[5] Ibid., 60; 47.

[6] Haussler, “The History of the Seventh-Day Adventist Church in California”: 164-5.