17

Learning Objectives

- Define feminism, sexism, and patriarchy.

- Examine the feminist movement.

- Discuss evidence for a decline in sexism.

In the national General Social Survey (GSS), slightly more than one-third of the public agrees with this statement: “It is much better for everyone involved if the man is the achiever outside the home and the woman takes care of the home and family.” Do you agree or disagree with this statement? If you are like the majority of college students, you disagree.

Today a lot of women, and some men, will say, “I’m not a feminist, but…,” and then go on to add that they hold certain beliefs about women’s equality and traditional gender roles that actually fall into a feminist framework. Their reluctance to self-identify as feminists underscores the negative image that feminists and feminism have but also suggests that the actual meaning of feminism may be unclear.

Feminism and sexism are generally two sides of the same coin. Feminism refers to the belief that women and men should have equal opportunities in economic, political, and social life, while sexism refers to a belief in traditional gender role stereotypes and in the inherent inequality between men and women. Sexism thus parallels the concept of racial and ethnic prejudice discussed in Chapter 3 “Racial and Ethnic Inequality”. Women and people of color are both said, for biological and/or cultural reasons, to lack certain qualities for success in today’s world.

Feminism as a social movement began in the United States during the abolitionist period before the Civil War. Elizabeth Cady Stanton (left) and Lucretia Mott (right) were outspoken abolitionists who made connections between slavery and the oppression of women.

The US Library of Congress – public domain; The US Library of Congress – public domain.

FEMINISM

Many thanks to Miliann Kang, Donovan Lessard, Laura Heston, and Sonny Nordmarken for a comprehensive OER source text.

Summary of The Women’s Movement Toward Equality

What equality means changes depending on societal structures. In the 1920s, the vote for white women and financial independence from husbands seemed a daunting goal. Then in the 1960s, the right to keep those Rosie the Riveter jobs and The Voting Rights Act of 1965 that finally gave Black women access to the voting booth was a significant fight. Then again, following the 1980s recession and color-blind racism, a third wave attempted to be more inclusive and talked openly about not centering white and educated women’s experiences over often marginalized women. This fourth wave is still under discussion, but combating domestic violence, sexual harassment, and other forms of misogyny are at the forefront. This fourth wave uses social media as a mobilizing tool and is more inclusive of LGBTQIA folx.

- First wave crested in the 1920s, Right to Vote

- Second wave crested in the 1960s, Right to Work

- Third wave crested in the 1980s and 90s, Equal Pay for Equal Work

- Fourth wave started a bit before 2012, Holding the Patriarchy Accountable

Expanded version: Feminist Movements

Feminist historian Elsa Barkley Brown reminds us that social movements and identities are not separate from each other, as we often imagine they are in contemporary society. There is some overlap between different “waves” of the 100+ year feminist movement in the United States, as there are evolving goals and degrees of societal resistance to women’s equality. The central feminist movement’s focus of equality shifts as some goals are achieved, modified, shifted, postponed, or discarded. It is also important to note that the dominant power structure of the time defines whose goals are promoted, achieved, and who benefits the most from the effort.

The feminist movement has some notable figures and some significant accomplishments, but it is important to remember that this history of notables hides that most of the work and sacrifice was made by the anonymous community of organizers behind the headlines. And that many of the people, particularly women of color, did not reap the rewards of their labor in the way that white women did.

19th Century Feminist Movements

What has come to be called the first wave of the feminist movement began in the mid 19th century and lasted until the passage of the 19th Amendment in 1920, which gave white women the right to vote. White middle-class first wave feminists in the 19th century to early 20th century, such as suffragist leaders Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, primarily focused on women’s suffrage (the right to vote), gaining access to education and employment, and striking down coverture – laws declaring that women’s legal rights and obligations are under their husband’s authority. These goals are famously enshrined in the Seneca Falls Declaration of Sentiments, which is the resulting document of the first women’s rights convention in the United States in 1848.

Demanding women’s enfranchisement, the abolition of coverture, and access to employment and education were quite radical demands at the time. These demands confronted the ideology of the cult of true womanhood, summarized in four key tenets—piety, purity, submission and domesticity—which held that white women were rightfully and naturally located in the private sphere of the household and not fit for public, political participation or labor in the waged economy. This first wave of the feminist movement was very much driven by the goals of white and affluent women. It is important to note that the ideological target of this movement, the cult of true womanhood, by definition, excludes Black and working-class women because they labored outside of the home.

The passage of the 19th Amendment in 1920 provided a test for the argument that granting women the right to vote would give them unfettered access to institutions and equality with men. History paints the passage of the 19th Amendment as the moment women secured the right to vote in the United States, but most Black women, many of whom had worked exhaustively for the rights of women to vote, did not achieve the vote until nearly five decades later. This is because Jim Crow laws in states across the country, and the unchecked violence of the Ku Klux Klan, prevented Black women and men from access to voting, education, employment, and public facilities. While equal rights existed in the abstract realm of the law under the 13th and 19th amendments, the on-the-ground reality of continued racial and gender inequality was quite different.

Early to Late 20th Century Feminist Movements

The second wave of the feminist movement does not have a clear cut start because the work from the 1920s never ended, it just evolved. But there is definitely a shift in focus with World War II, and the decade following World War II generally defines our second wave. Of course there is significant intersection between second wave feminism and the Civil Rights Movement. Just as the first wave prioritized white, middle-class, women’s goals while it gladly accepted the labor of Black women and poor women, the second wave did too.

While millions of poor women and BIPOC women were already working in the United States at the beginning of World War II, labor shortages during World War II allowed millions of women to move into higher-paying factory jobs that had previously been occupied by men. And then when soldiers returned to the states following the end of the war, they came home to women who had been working in jobs, earning decent money, controlling their own homes, and making the decisions about their own spending.

The second wave feminist movement focused generally on fighting patriarchal structures of power, and specifically on combating occupational sex segregation in employment and fighting for reproductive rights for women. However, this was not the only source of second wave feminism, and white women were not the only women spearheading feminist movements. As historian Becky Thompson (2002) argues, in the mid and late 1960s, Latina women, African American women, and Asian American women were developing multiracial feminist organizations that would become important players within the U.S. second wave feminist movement.

In many ways, the second wave feminist movement was influenced and facilitated by the activist tools provided by the civil rights movement. Drawing on the stories of women who participated in the civil rights movement, historians Ellen Debois and Lynn Dumenil (2005) argue that women’s participation in the civil rights movement allowed them to challenge gender norms that held that women belonged in the private sphere, and not in politics or activism. Not only did many women who were involved in the civil rights movement become activists in the second wave feminist movement, they also employed tactics that the civil rights movement had used, including marches and non-violent direct action. Additionally, the Civil Rights Act of 1964—a major legal victory for the civil rights movement—not only prohibited employment discrimination based on race, but Title VII of the Act also prohibited sex discrimination. When the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC)—the federal agency created to enforce Title VII—largely ignored women’s complaints of employment discrimination, 15 women and one man organized to form the National Organization of Women (NOW), which was modeled after the NAACP. NOW focused its attention and organizing on passage of the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), fighting sex discrimination in education, and defending Roe v. Wade—the Supreme Court decision of 1973 that struck down state laws that prohibited abortion within the first three months of pregnancy.

Third Wave Feminism

Third wave feminism is, in many ways, a hybrid creature. It is influenced by second wave feminism, Black feminisms, transnational feminisms, Global South feminisms, and queer feminism. This hybridity of third wave activism comes directly out of the experiences of feminists in the late 20th and early 21st centuries who have grown up in a world that supposedly does not need social movements because “equal rights” for racial minorities, sexual minorities, and women have been guaranteed by law in most countries. The gap between law and reality—between the abstract proclamations of states and concrete lived experience—however, reveals the necessity of both old and new forms of activism.

In the 1980s and 1990s, third wave feminists took up activism in a number of forms, ultimately resulting in the 1994 hotly debated and legally contested Violence Against Women Act. Also significant is the 1980s AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP), which began organizing to press an unwilling US government and medical establishment to develop affordable drugs for people with HIV/AIDS. In the latter part of the 1980s, a more radical subset of individuals began to articulate a queer politics, explicitly reclaiming a derogatory term often used against gay men and lesbians, and distancing themselves from the gay and lesbian rights movement, which they felt mainly reflected the interests of white, middle-class gay men and lesbians.

In this vein, Lisa Duggan (2002) coined the term homonormativity, which describes the normalization and de-politicization of gay men and lesbians through their assimilation into capitalist economic systems and domesticity—individuals who were previously constructed as “other.” These individuals thus gained entrance into social life at the expense and continued marginalization of people who were non-white, disabled, trans, single or non-monogamous, middle-class, or non-western. Critiques of homonormativity were also critiques of gay identity politics, which left out concerns of many gay individuals who were marginalized within gay groups. There is a prominent author of children’s wizardry books who is very publicly third wave feminist and caustically transphobic. Because this is a rather common theme for third wave, a fourth distinction is brewing.

Defining the Fourth Wave -starting somewhere around 2012

There are plenty of people who are not convinced we are in a fourth wave of the feminist movement. Yet the conversations of today are markedly different than the pantsuits and political organizing of the 90s. Within the last decade the volume of protest and legal action has intensified, and the movement is getting results (#MeToo, #YesAllWomen, etc.). This generation’s young people are more politically active, more inclusive, and are more vocal in their advocacy. While intersectionality was very much a part of third wave feminism, fourth wave feminism embraces gender fluidity and the LGBTQIA community, and mixes racial justice, environmental justice, economic justice, etc. into activism. This wave uses social media as a tool for propelling social change in a way that was inconceivable in the 1990s.

The emphasis on coalitional politics and making connections between several movements is another crucial contribution of feminist activism and scholarship. In the 21st century, feminist movements confront an array of structures of power: global capitalism, the prison system, war, racism, ableism, heterosexism, and transphobia, among others. What kind of world do we wish to create and live in? What alliances and coalitions will be necessary to challenge these structures of power? How do feminists, queers, people of color, trans people, disabled people, and working-class people go about challenging these structures of power? These are among some of the questions that feminist activists are grappling with now, and their actions point toward a deepening commitment to an intersectional politics of social justice and praxis.

The Growth of Feminism and the Decline of Sexism

Several varieties of feminism exist. Although they all share the basic idea that women and men should be equal in their opportunities in all spheres of life, they differ in other ways (Hannam, 2012). Liberal feminism believes that the equality of women can be achieved within our existing society by passing laws and reforming social, economic, and political institutions. In contrast, socialist feminism blames capitalism for women’s inequality and says that true gender equality can result only if fundamental changes in social institutions, and even a socialist revolution, are achieved. Radical feminism, on the other hand, says that patriarchy (male domination) lies at the root of women’s oppression and that women are oppressed even in noncapitalist societies. Patriarchy itself must be abolished, they say, if women are to become equal to men. Finally, multicultural feminism emphasizes that women of color are oppressed not only because of their gender but also because of their race and class. They thus face a triple burden that goes beyond their gender. By focusing their attention on women of color in the United States and other nations, multicultural feminists remind us that the lives of these women differ in many ways from those of the middle-class women who historically have led US feminist movements.

What evidence is there for the impact of the contemporary women’s movement on public thinking? The GSS, the Gallup poll, and other national surveys show that the public has moved away from traditional views of gender toward more modern ones. Another way of saying this is that the public has moved from sexism toward feminism.

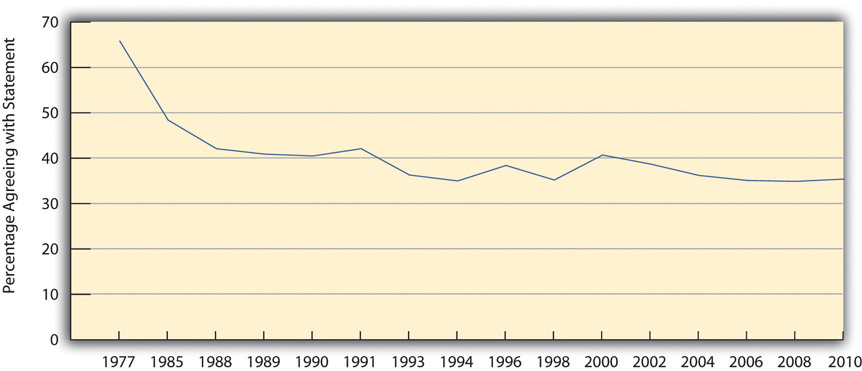

To illustrate this, let’s return to the GSS statement that it is much better for the man to achieve outside the home and for the woman to take care of home and family. Figure 4.2 “Change in Acceptance of Traditional Gender Roles in the Family, 1977–2010” shows that agreement with this statement dropped sharply during the 1970s and 1980s before leveling off afterward to slightly more than one-third of the public.

Figure 4.2 Change in Acceptance of Traditional Gender Roles in the Family, 1977–2010

Percentage agreeing that “it is much better for everyone involved if the man is the achiever outside the home and the woman takes care of the home and family.”

Source: Data from General Social Surveys. (1977–2010). Retrieved from http://sda.berkeley.edu/cgi-bin/hsda?harcsda+gss10.

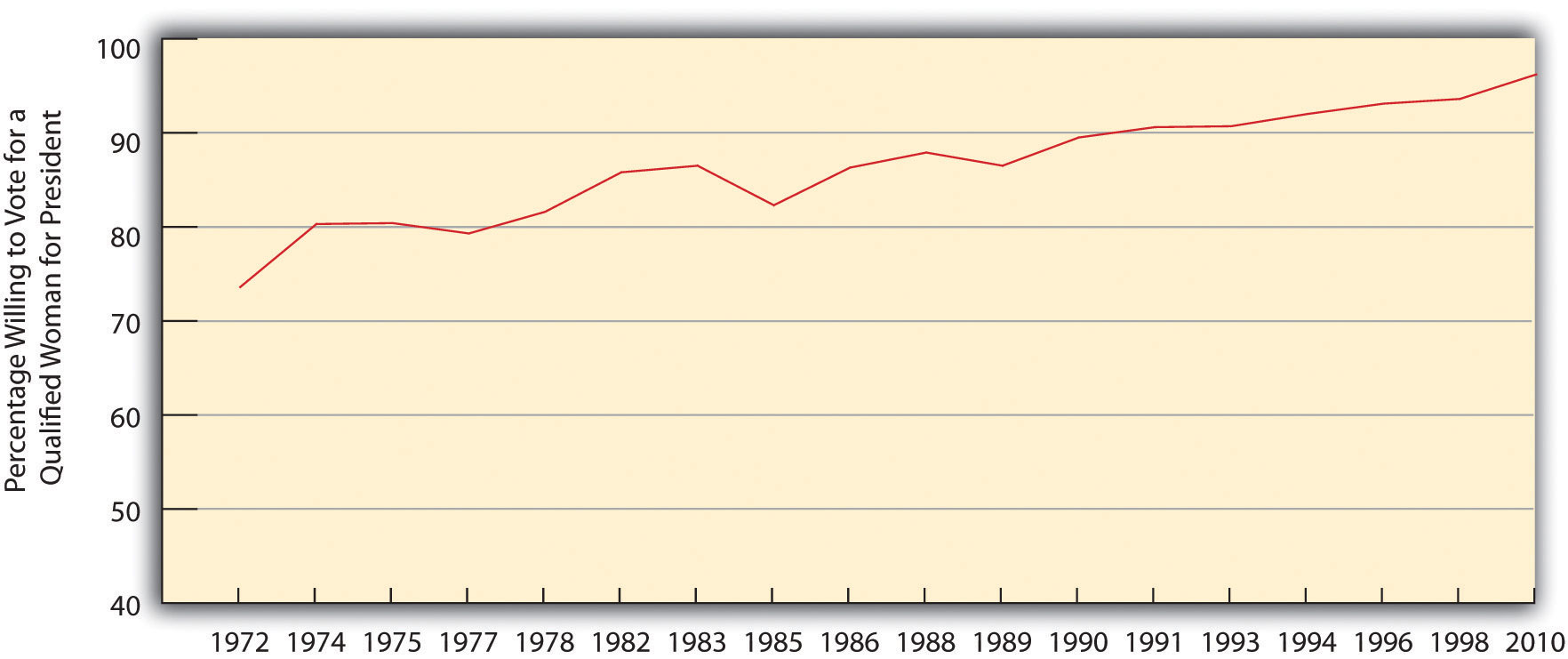

Another GSS question over the years has asked whether respondents would be willing to vote for a qualified woman for president of the United States. As Figure 4.3 “Change in Willingness to Vote for a Qualified Woman for President” illustrates, this percentage rose from 74 percent in the early 1970s to a high of 96.2 percent in 2010. Although we have not yet had a woman president, despite Hillary Rodham Clinton’s historic presidential primary campaign in 2007 and 2008 and Sarah Palin’s presence on the Republican ticket in 2008, the survey evidence indicates the public is willing to vote for one. As demonstrated by the responses to the survey questions on women’s home roles and on a woman president, traditional gender views have indeed declined.

Figure 4.3 Change in Willingness to Vote for a Qualified Woman for President

Source: Data from General Social Survey. (2010). Retrieved from http://sda.berkeley.edu/cgi-bin/hsda?harcsda+gss10.

Key Takeaways

- Feminism refers to the belief that women and men should have equal opportunities in economic, political, and social life, while sexism refers to a belief in traditional gender role stereotypes and in the inherent inequality between men and women.

- Sexist beliefs have declined in the United States since the early 1970s.

For Your Review

- Do you consider yourself a feminist? Why or why not?

- Think about one of your parents or of another adult much older than you. Does this person hold more traditional views about gender than you do? Explain your answer.

References

Barkley Brown, E. 1997. “What has happened here’: The Politics of Difference in Women’s History and Feminist Politics,” Pp. 272-287 in The Second Wave: A Reader in Feminist Theory, edited by Linda Nocholson. New York, NY: Routledge.

Cott, N. 2000. Public Vows: A History of Marriage and the Nation. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Davis, Angela. 1983. Women, Race, Class. New York, NY: Random House.

— 1981. “Working Women, Black Women and the History of the Suffrage Movement,” Pp. 73-78 in A Transdisciplinary Introduction to Women’s Studies, edited by Avakian, A. and A. Deschamps. Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company.

Debois, E. and L. Dumenil. 2005. Through Women’s Eyes: An American History With Documents. St. Martin Press.

Duggan, Lisa. 2002. “The New Homonormativity: The Sexual Politics of Neoliberalism.” Pp. 175-194 in Materializing Democracy, edited by R. Castronovo and D. Nelson. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Durso, L.E., & Gates, G.J. 2012. “Serving Our Youth: Findings from a National Survey of Service Providers Working with Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Youth who are Homeless or At Risk of Becoming Homeless.” Los Angeles: The Williams Institute with True Colors Fund and The Palette Fund.

Hannam, J. (2012). Feminism. New York, NY: Pearson Longman.

Hayden, C. and M. King. 1965. “Sex and Caste: A Kind of Memo.” Available at: http://www.historyisaweapon.com/defcon1/sexcaste.html. Accessed 3 May, 2011.

Hernandez, D. and B. Rehman. 2002. Colonize This! Young Women of Color on Today’s Feminism. New York, NY: Seal Press.

Heywood, L. and J. Drake. 1997. Third Wave Agenda: Being Feminist, Doing Feminism. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

hooks, bell. 1984. Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center, second ed. Cambridge, MA: South End Press.

Institute for Women’s Policy Research. 2016. “Compilation of U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Survey. Historical Income Tables: Table P-38. Full-Time, Year Round Workers by Median Earnings and Sex: 1987 to 2015.” Available at: https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/incomepoverty/historical-income-people.html. Accessed 8 June, 2017.

James, S. E., Herman, J. L., Rankin, S., Keisling, M., Mottet, L., & Ana , M. 2016. The Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey. Washington, DC: National Center for Transgender Equality.

Kang, Miliann, Donovan Lessard, Laura Heston, Sonny Nordmarken. Introduction to Women, Gender, Sexuality Studies. University of Amherst, Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. http://www.oercommons.org/courses/introduction-to-women-gender-sexuality-studies/view

Mohanty, Chandra Talpade. 1991. “Under Western Eyes: Feminist Scholarship and Colonial Discourses”. In Third World Women and the Politics of Feminism, ed. Mohanty, Chandra Talpade, Ann Russo, and Lourdes Torres. Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

Odo, Franklin. 2017. “How a Segregated Regiment of Japanese Americans Became One of WWII’s Most Decorated.” New America. Available at: https://www.newamerica.org/weekly/edition-150/how-segregated-regiment-japanese-americans-became-one-wwiis-most-decorated/. Accessed 15 May, 2017.

Painter, Nell. 1996. Sojourner Truth: A Life, A Symbol. New York: W.W. Norton.

Puar, Jasbir. 2007. Terrorist Assemblages: Homonationalism in Queer Times. Durham: Duke University Press.

Rubin, G. 1984. “Thinking Sex: Notes for a Radical Theory of the Politics of Sexuality,” in Carole Vance, ed., Pleasure and Danger. New York, NY: Routledge.

Sommers, Christina Hoff. 1994. Who Stole Feminism? How Women Have Betrayed Women. New York: Doubleday.

Takaki, Ronald. 2001. Double Victory: A Multicultural History of America in World War II. Back Bay Books.

Thompson, Becky. 2002. “Multiracial Feminism: Recasting the Chronology of Second Wave Feminism,” Feminist Studies 28(2): 337-360.

Truth, Sojourner. 1851. “Ain’t I a Woman?” Available at: http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/mod/sojtruth-woman.html. Accessed 3 May, 2011.

Wells, Ida B. 1893. “Lynch Law.” Available at: http://www.historyisaweapon.com/defcon1/wellslynchlaw.html. Accesssed 15 May, 2017.

Zinn, H. 2003. A People’s History of the United States: 1492-Present. New York, NY: HarperCollins.