Chapter 10: The Changing Family

Social Problems in the News

“Help for Domestic Violence Victims Declining,” the headline said. In Georgia, donations and other financial assistance to battered women’s shelters were dwindling because of the faltering economy. This decreased funding was forcing the shelters to cut back their hours and lay off employees. As Meg Rogers, the head of a shelter with a six-month waiting list explained, “We are having to make some very tough decisions.”

Reflecting her experience, shelters in Georgia had to turn away more than 2,600 women and their children in the past year because of lack of space. Many women had to return to the men who were abusing them. This situation troubled Rogers. “I think their safety is being compromised,” she said. “They may go to the abuser’s family even if they don’t go back to the abuser.” A domestic violence survivor also worried about their fate and said she owed her own life to a women’s shelter: “I love them to this day and I’m alive because of them.”

Source: Simmons, 2011

Once upon a time, domestic violence did not exist, or so the popular television shows of the 1950s would have had us believe. Neither did single-parent households, gay couples, interracial couples, mothers working outside the home, heterosexual spouses deciding not to have children, or other family forms and situations that are increasingly common today. Domestic violence existed, of course, but it was not something that television shows and other popular media back then depicted. The other family forms and situations also existed to some degree but have become much more common today.

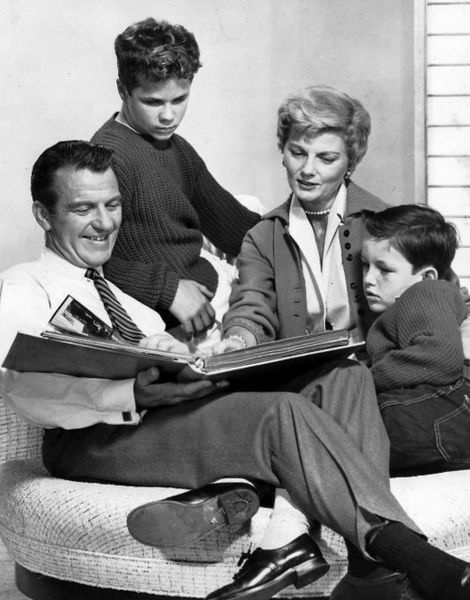

Families shown in today’s television shows are very different from the traditional family depicted in popular television shows of the 1950s. Television families from the 1950s consisted of two heterosexual parents, with the father working outside the home and the mother staying at home with two or more wholesome children.

The Bees Knees Daily – Cast photo of the Cleaver Family from “Leave It To Beaver” – CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

The 1950s gave us Leave It to Beaver and other television shows that depicted loving, happy, “traditional” families living in the suburbs. The father worked outside the home, the mother stayed at home to take care of the kids and do housework, and their children were wholesome youngsters who rarely got into trouble and certainly did not use drugs or have sex. Today we have ABC’s Modern Family, which features one traditional family (two heterosexual parents and their three children) and two nontraditional families (one with an older white man and a younger Latina woman and her child, and another with two gay men and their adopted child). Many other television shows today and in recent decades have featured divorced couples or individuals, domestic violence, and teenagers doing drugs or committing crime.

In the real world, we hear that parents are too busy working at their jobs to raise their kids properly. We hear of domestic violence as in the story from Georgia at the start of this chapter. We hear of kids living without fathers, because their parents are divorced or never were married in the first place. We hear of young people having babies, using drugs, and committing violence. We hear that the breakdown of the nuclear family, the entrance of women into the labor force, and the growth of single-parent households are responsible for these problems. Some observers urge women to work only part-time or not at all so they can spend more time with their children. Some yearn wistfully for a return to the 1950s, when everything seemed so much easier and better. Children had what they needed back then: one parent to earn the money, and another parent to take care of them full time until they started kindergarten, when this parent would be there for them when they came home from school.

Families have indeed changed, but this yearning for the 1950s falls into what historian Stephanie Coontz (2000) calls the “nostalgia trap.” The 1950s television shows did depict what some families were like back then, but they failed to show what many other families were like. Moreover, the changes in families since that time have probably not had all the harmful effects that many observers allege. Historical and cross-cultural evidence even suggests that the Leave It to Beaver-style family of the 1950s was a relatively recent and atypical phenomenon and that many other types of families can thrive just as well as the 1950s television families did.

This chapter expands on these points and looks at today’s families and the changes they have undergone. It also examines some of the controversies and problems now surrounding families and relationships.

References

Coontz, S. (2000). The way we never were: American families and the nostalgia trap. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Simmons, A. (2011, October 29). Help for domestic violence victims declining. The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved from http://www.ajc.com/news/crime/help-for-domestic-violence-1212373.html.