50

Learning Objectives

- Discuss why the US divorce rate rose during the 1960s and 1970s and summarize the major individual-level factors accounting for divorce today.

- Describe the effects of divorce for spouses and children.

- Summarize the evidence on how children fare when their mothers work outside the home.

- Describe the extent of family violence and explain why it occurs.

According to the census, roughly 6 million opposite-sex couples are currently cohabiting in the United States. The average cohabitation lasts less than two years.

Amit Gupta – CC BY-NC 2.0.

American families have undergone many changes since the 1950s. Scholars, politicians, and the public have strong and often conflicting views on the reasons for these changes and on their consequences. We now look at some of the most important issues affecting US families through the lens of the latest social scientific evidence. Because Chapter 5 “Sexual Orientation and Inequality” on sexual orientation and inequality discussed same-sex marriage and families, please refer back to that chapter for material on this very important topic.

Cohabitation

Some people who are not currently married nonetheless cohabit, or live together, with someone of the opposite sex in a romantic relationship. The census reports that about 6 million opposite-sex couples are currently cohabiting; these couples constitute about 10 percent of all opposite-sex couples (married plus unmarried) who live together. The average cohabitation lasts less than two years and ends when the couple either splits up or gets married; about half of cohabiting couples do marry, and half split up. More than half of people in their twenties and thirties have cohabited, and roughly one-fourth of this age group is currently cohabiting (Brown, 2005). Roughly 55 percent of cohabiting couples have no biological children, about 45 percent live with a biological child of one of the partners, and 21 percent live with their own biological child. (These figures add to more than 100 percent because many couples live with their own child and a child of a partner.) About 5 percent of children live with biological parents who are cohabiting.

Interestingly, many studies find that married couples who have cohabited with each other before getting married are more likely to divorce than married couples who did not cohabit (Jose, O’Leary, & Moyer, 2010). As sociologist Susan L Brown (2005, p. 34) notes, this apparent consequence is ironic: “The primary reason people cohabit is to test their relationship’s viability for marriage. Sorting out bad relationships through cohabitation is how many people think they can avoid divorce. Yet living together before marriage actually increases a couple’s risk of divorce.” Two reasons may account for this result. First, cohabitation may change the relationship between a couple and increase the chance they will divorce if they get married anyway. Second, individuals who are willing to live together without being married may not be very committed to the idea of marriage and thus may be more willing to divorce if they are unhappy in their eventual marriage.

Recent research compares the psychological well-being of cohabiting and married adults and also the behavior of children whose biological parent or parents are cohabiting rather than married (Apel & Kaukinen, 2008; Brown, 2005). On average, married adults are happier and otherwise have greater psychological well-being than cohabiting adults, while the latter, in turn, fare better psychologically than adults not living with anyone. Research has not yet clarified the reasons for these differences, but it seems that people with the greatest psychological and economic well-being are most likely to marry. If this is true, it is not the state of being married per se that accounts for the difference in well-being between married and cohabiting couples, but rather the extent of well-being that affects decisions to marry or not marry. Another difference between cohabitation and marriage concerns relationship violence. Among young adults (aged 18–28), this type of violence is more common among cohabiting couples than among married or dating couples. The reasons for this difference remain unknown but may again reflect differences in the types of people who choose to cohabit (Brown & Bulanda, 2008).

The children of cohabiting parents tend to exhibit lower well-being of various types than those of married parents: They are more likely to engage in delinquency and other antisocial behavior, and they have lower academic performance and worse emotional adjustment. The reasons for these differences remain to be clarified but may again stem from the types of people who choose to cohabit rather than marry.

Divorce and Single-Parent Households

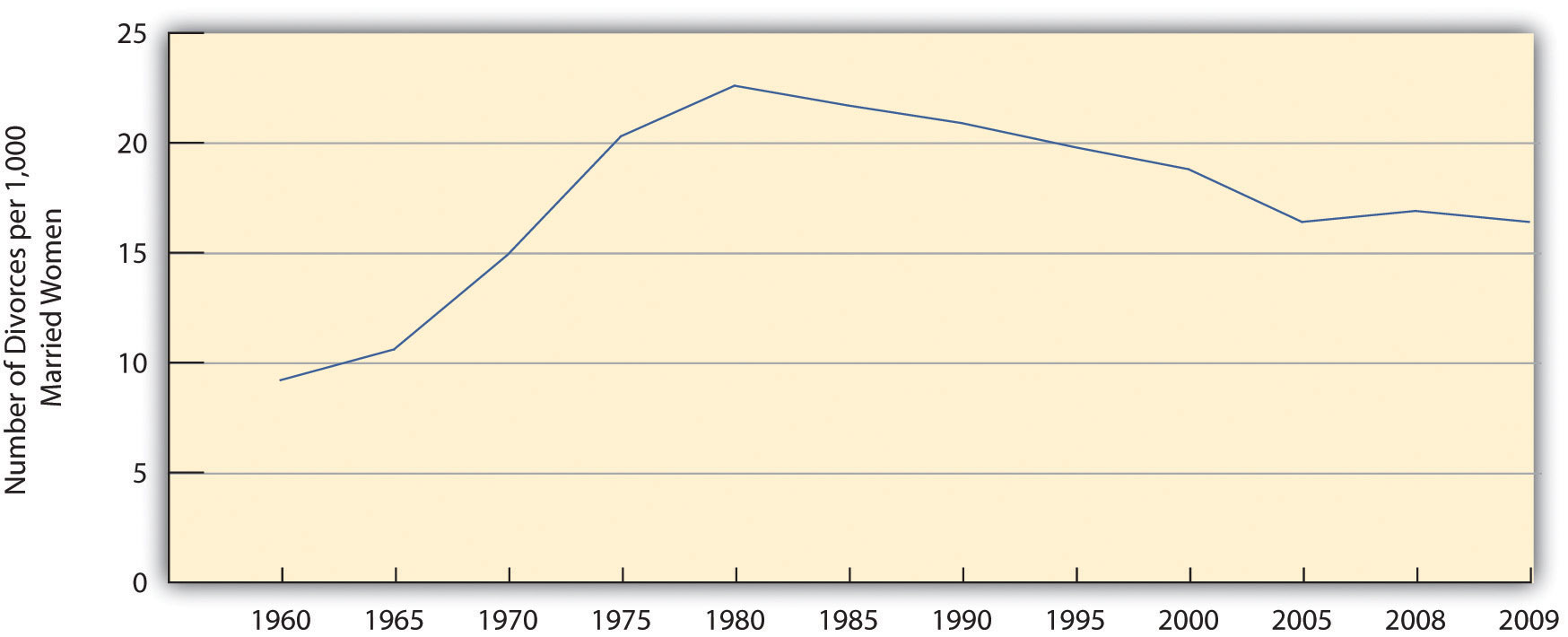

The US divorce rate has risen since the early 1900s, with several peaks and valleys, and is now the highest in the industrial world. It rose sharply during the Great Depression and World War II, probably because of the economic distress of the former and the family disruption caused by the latter, and fell sharply after the war as the economy thrived and as marriage and family were proclaimed as patriotic ideals. It dropped a bit more during the 1950s before rising sharply through the 1960s and 1970s (Cherlin, 2009). The divorce rate has since declined somewhat (see Figure 10.4 “Number of Divorces per 1,000 Married Women Aged 15 or Older, 1960–2009”) and today is only slightly higher than its peak at the end of World War II. Still, the best estimates say that 40–50 percent of all new marriages will one day end in divorce (Teachman, 2008). The surprising announcement in June 2010 of the separation of former vice president Al Gore and his wife, Tipper, was a poignant reminder that divorce is a common outcome of many marriages.

Figure 10.4 Number of Divorces per 1,000 Married Women Aged 15 or Older, 1960–2009

Source: Data from Wilcox, W. B. (Ed.). (2010). The state of our unions, 2010: Marriage in America. Charlottesville, VA: National Marriage Project.

Reasons for Divorce

We cannot be certain about why the divorce rate rose so much during the 1960s and 1970s, but we can rule out two oft-cited causes. First, there is little reason to believe that marriages became any less happy during this period. We do not have good data to compare marriages then and now, but the best guess is that marital satisfaction did not decline after the 1950s ended. What did change was that people after the 1950s became more willing to seek divorces in marriages that were already unhappy.

Second, although the contemporary women’s movement is sometimes blamed for the divorce rate by making women think marriage is an oppressive institution, the trends in Figure 10.4 “Number of Divorces per 1,000 Married Women Aged 15 or Older, 1960–2009” suggest this blame is misplaced. The women’s movement emerged in the late 1960s and was capturing headlines by the early 1970s. Although the divorce rate obviously rose after that time, it also started rising several years before the women’s movement emerged and captured headlines. If the divorce rate began rising before the women’s movement started, it is illogical to blame the women’s movement. Instead, other structural and cultural forces must have been at work, just as they were at other times in the last century, as just noted, when the divorce rate rose and fell.

Why, then, did divorce increase during the 1960s and 1970s? One reason is the increasing economic independence of women. As women entered the labor force in the 1960s and 1970s, they became more economically independent of their husbands, even if their jobs typically paid less than their husbands’ jobs. When women in unhappy marriages do become more economically independent, they are more able to afford to get divorced than when they have to rely entirely on their husbands’ earnings (Hiedemann, Suhomlinova, & O’Rand, 1998). When both spouses work outside the home, moreover, it is more difficult to juggle the many demands of family life, and family life can be more stressful. Such stress can reduce marital happiness and make divorce more likely. Spouses may also have less time for each other when both are working outside the home, making it more difficult to deal with problems they may be having.

Disapproval of divorce has declined since the 1950s, and divorce is now considered a normal if unfortunate part of life.

John C Bullas BSc MSc PhD MCIHT MIAT – Divorce Cakes a_005 – CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

It is also true that disapproval of divorce has declined since the 1950s, even if negative views of it still remain (Cherlin, 2009). Not too long ago, divorce was considered a terrible thing; now it is considered a normal if unfortunate part of life. We no longer say a bad marriage should continue for the sake of the children. When New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller ran for president in the early 1960s, the fact that he had been divorced hurt his popularity, but when California Governor Ronald Reagan ran for president less than two decades later, the fact that he had been divorced was hardly noted. Many presidential candidates and other politicians today have been divorced. But is the growing acceptability of divorce a cause of the rising divorce rate, or is it the result of the rising divorce rate? Or is it both a cause and a result? This important causal order question is difficult to resolve.

Another reason divorce rose during the 1960s and 1970s may be that divorces became easier to obtain legally. In the past, most states required couples to prove that one or both had committed actions such as mental cruelty, adultery, or other such behaviors in order to get divorced. Today almost all states have no-fault divorce laws that allow a couple to divorce if they say their marriage has failed from irreconcilable differences. Because divorce has become easier and less expensive to obtain, more divorces occur. But are no-fault divorce laws a cause or result of the post-1950s rise in the divorce rate? The divorce rate increase preceded the establishment of most states’ no-fault laws, but it is probably also true that the laws helped make additional divorces more possible. Thus no-fault divorce laws are probably one reason for the rising divorce rate after the 1950s, but only one reason (Kneip & Bauer, 2009).

We have just looked at possible reasons for divorce rate trends, but we can also examine the reasons why certain marriages are more or less likely to end in divorce within a given time period. Although, as noted earlier, 40–50 percent of all new marriages will probably end in divorce, it is also true that some marriages are more likely to end than others. Family scholars identify several correlates of divorce (Clarke-Stewart & Brentano, 2006; Wilcox, 2010). An important one is age at marriage: Teenagers who get married are much more likely to get divorced than people who marry well into their twenties or beyond, partly because they have financial difficulties and are not yet emotionally mature. A second correlate of divorce is social class: People who are poor and have less formal education at the time of their marriage are much more likely to get divorced than people who begin their marriages in economic comfort and with higher levels of education.

Effects of Divorce and Single-Parent Households

Much research exists on the effects of divorce on spouses and their children, and scholars often disagree on what these effects are. One thing is clear: Divorce plunges many women into poverty or near-poverty (Gadalla, 2008; Wilcox, 2010). Many have been working only part time or not at all outside the home, and divorce takes away their husband’s economic support. Even women working full time often have trouble making ends meet, because many are in low-paying jobs. One-parent families headed by a woman for any reason are much poorer ($32,031 in 2010 median annual income) than those headed by a man ($49,718). Meanwhile, the median income of married-couple families is much higher ($72,751). Almost 32 percent of all single-parent families headed by women are officially poor, compared to only about 16 percent of single-parent families headed by men and 6 percent of married-couple families (DeNavas-Walt, Proctor, & Smith, 2011).

Although the economic consequences of divorce seem clear, what are the psychological consequences for husbands, wives, and their children? Are they better off if a divorce occurs, worse off, or about the same?

Effects on Spouses

The research evidence for spouses is very conflicting. Many studies find that divorced spouses are, on average, less happy and have poorer mental health after their divorce, but some studies find that happiness and mental health often improve after divorce (Cherlin, 2009; Waite, Luo, & Lewin, 2009). The postdivorce time period that is studied may affect what results are found: For some people psychological well-being may decline in the immediate aftermath of a divorce, given how difficult the divorce process often is, but rise over the next few years. The contentiousness of the marriage also matters. Some marriages ending in divorce have been filled with hostility, conflict, and sometimes violence, while other marriages ending in divorce have not been very contentious at all, even if they have failed. Individuals seem to fare better psychologically after ending a very contentious marriage but fare worse after ending a less contentious marriage (Amato & Hohmann-Marriott, 2007).

Effects on Children

What about the children? Parents used to stay together “for the sake of the children,” thinking that divorce would cause their children more harm than good. Studies of this issue generally find that children in divorced families are indeed more likely, on average, to do worse in school, to use drugs and alcohol and suffer other behavioral problems, and to experience emotional distress and other psychological problems (Wilcox, 2010). The trauma of the divorce and the difficulties that single parents encounter in caring for and disciplining children are thought to account for these effects.

However, two considerations suggest that children of divorce may fare worse for reasons other than divorce trauma and the resulting single-parent situation. First, most children whose parents divorce end up living with their mothers. As we just noted, many divorced women and their children live in poverty or near poverty. To the extent that these children fare worse in many ways, their mothers’ low incomes may be a contributing factor. Studies of this issue find that divorced mothers’ low incomes do, in fact, help explain some of the difficulties that their children experience (Demo & Fine, 2010). Divorce trauma and single-parenthood still matter for children’s well-being in many of these studies, but the worsened financial situation of divorced women and their children also makes a difference.

Second, it is possible that children do worse after a divorce because of the parental conflict that led to the divorce, not because of the divorce itself. It is well known that the quality of the relationship between a child’s parents affects the child’s behavior and emotional well-being (Moore, Kinghorn, & Bandy, 2011). This fact raises the possibility that children may fare better if their parents end a troubled marriage than if their parents stay married. Recent studies have investigated this issue, and their findings generally mirror the evidence for spouses just cited: Children generally fare better if their parents end a highly contentious marriage, but they fare worse if their parents end a marriage that has not been highly contentious (Hull et al., 2012). As one researcher summarizes this new body of research, “All these new studies have discovered the same thing: The average impact of divorce in society at large is to neither increase nor decrease the behavior problems of children. They suggest that divorce, in and of itself, is not the cause of the elevated behavior problems we see in children of divorce” (Li, 2010, p. 174). Commenting on divorces from highly contentious marriages, sociologist Virginia E. Rutter (2010, p. 169) bluntly concludes, “There are times and situations when divorce is beneficial to the people who divorce and to their children.”

Fathers and Children

Recall that most children whose parents are not married, either because they divorced or because they never were married, live with their mothers. Another factor that affects how children in these situations fare is the closeness of the child-father relationship. Whether or not children live with their fathers, they fare better in many respects when they have an emotionally close relationship with their fathers. This type of relationship is certainly more possible when they live with their fathers, and this is a reason that children who live with both their parents fare better on average than children who live only with their mother. However, some children who do live with their fathers are less close to them than some children who live apart from their fathers.

Recent research by sociologist Alan Booth and colleagues (Booth, Scott, & King, 2010) found that the former children fare worse than the latter children. As Booth et al. (2010, p. 600) summarize this result, “We find that adolescents who are close to their nonresident fathers report higher self-esteem, less delinquency, and fewer depressive symptoms than adolescents who live with a father with whom they are not close. It appears that adolescents benefit more from a close bond to a nonresident father than a weak bond to a resident father.” To the extent this is true, they add, “youth are not always better off in two-parent families.” In fact, children who are not close to a father with whom they live have lower self-esteem than children who are not close to a father with whom they do not live. Overall, though, children fare best when they live with fathers with whom they have a close relationship: “It does not appear that strong affection alone can overcome the problems associated with father absence from the child’s residence.”

Marriage and Well-Being

Is marriage good for people? This is the flip side of the question we have just addressed on whether divorce is bad for people. Are people better off if they get married? Or are they better off if they stay single?

In 1972, sociologist Jessie Bernard (1972) famously said that every marriage includes a “her marriage” and a “his marriage.” By this she meant that husbands and wives view and define their marriages differently. When spouses from the same marriage are interviewed, they disagree on such things as how often they should have sex, how often they actually do have sex, and who does various household tasks. Women do most of the housework and child care, while men are freer to work and do other things outside the home. Citing various studies, she said that marriage is better for men than for women. Married women, she said, have poorer mental health than unmarried women, while married men have better mental health than unmarried men. In short, she said that marriage was good for men but bad for women.

Married people are generally happier than unmarried people and score higher on other measures of psychological well-being.

Silvia Sala – CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Critics later said that Bernard misinterpreted her data on women and that married women are also better off than unmarried women (Glenn, 1997). Recent research generally finds that marriage does benefit both sexes: Married people, women and men alike, are generally happier than unmarried people (whether never married, divorced, or widowed), score better on other measures of psychological well-being, are physically healthier, have better sex lives, and have lower death rates (Waite et al., 2009; Wilcox, 2010). There is even evidence that marriage helps keep men from committing crime (Theobald & Farrington, 2011)! Marriage has these benefits for several reasons, including the emotional and practical support spouses give each other, their greater financial resources compared to those of unmarried people, and the sense of obligation they have toward each other.

Three issues qualify the general conclusion that marriage is beneficial (Frech & Williams, 2007). First, it would be more accurate to say that good marriages are beneficial, because bad marriages certainly are not, and stressful marriages can impair physical and mental health (Parker-Pope, 2010). Second, although marriage is generally beneficial, its benefits seem greater for older adults than for younger adults, for whites than for African Americans, and for individuals who were psychologically depressed before marriage than for those who were not depressed. Third, psychologically happy and healthy people may be the ones who get married in the first place and are less apt to get divorced once they do marry. If so, marriage does not promote psychological well-being; rather, psychological well-being promotes marriage. Research testing this selectivity hypothesis finds that both processes occur: Psychologically healthy people are more apt to get and stay married, but marriage also promotes psychological well-being.

Working Mothers and Day Care

As noted earlier, women are now much more likely to be working outside the home than a few decades ago. This is true for both married and unmarried women and also for women with and without children. As women have entered the labor force, the question of who takes care of the children has prompted much debate and controversy. Many observers say young children suffer if they do not have a parent, implicitly their mother, taking care of them full-time until they start school and being there every day when they get home from school. The public is divided on the issue of more mothers working outside the home: 21 percent say this trend is “a good thing for society”; 37 percent say it is “a bad thing for society”; and 46 percent say it “doesn’t make much difference” (Morin, 2010). What does research say about how young children fare if their mothers work? (Notice that no one seems to worry that fathers work!)

Early studies compared the degree of attachment shown to their mothers by children in day care and that shown by children who stay at home with their mothers. In one type of study, children were put in a laboratory room with their mothers and observed as the mothers left and returned. The day-care kids usually treated their mothers’ departure and returning casually and acted as if they did not care that their mothers were leaving or returning. In contrast the stay-at-home kids acted very upset when their mothers left and seemed much happier and even relieved when they returned. Several researchers concluded that these findings indicated that day-care children lacked sufficient emotional attachment to their mothers (Schwartz, 1983). However, other researchers reached a very different conclusion: The day-care children’s apparent nonchalance when their mothers left and returned simply reflected the fact that they always saw her leave and return every day when they went to day care. The lack of concern over her behavior showed only that they were more independent and self-confident than the stay-at-home children, who were fearful when their mothers left, and not that they were less attached to their mothers (Coontz, 1997).

More recent research has compared stay-at-home children and day-care children starting with infancy, with some of the most notable studies using data from a large study funded by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, a branch of the National Institutes of Health (Rabin, 2008). This research finds that day-care children exhibit better cognitive skills (reading and arithmetic) than stay-at-home children but are also slightly more likely to engage in aggressive behavior that is well within the normal range of children’s behavior. This research has also yielded two other conclusions. First, the quality of parenting and other factors such as parent’s education and income matter much more for children’s cognitive and social development than whether or not they are in day care. Second, to the extent that day care is beneficial for children, it is high-quality day care that is beneficial, as low-quality day care can be harmful.

Children in day care exhibit better cognitive skills than stay-at-home children but are also slightly more likely to engage in aggressive behavior that is within the normal range of children’s behavior.

njxw – Daycare – CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

This latter conclusion is an important finding, because many day-care settings in the United States are not high quality. Unfortunately, many parents who use day care cannot afford high-quality care, which can cost hundreds of dollars monthly. This problem reflects the fact that the United States lags far behind other Western democracies in providing subsidies for day care (see Note 10.21 “Lessons from Other Societies” later in this chapter). Because working women are certainly here to stay and because high-quality day care seems at least as good for children as full-time care by a parent, it is essential that the United States make good day care available and affordable.

Affordable child care is especially essential for low-income parents. After the United States plunged into economic recession in 2008, many states reduced their subsidies for child care. As a result, many low-income parents who wanted to continue working or to start a job could not afford to do so because child care can be very expensive: For a family living below the poverty line, child care comprises one-third of the family budget on the average. As the head of a California organization that advocates for working parents explained, “You can’t expect a family with young children to get on their feet and get jobs without child care” (Goodman, 2010, p. A1).

Racial and Ethnic Diversity in Marriages and Families

Marriages and families in the United States exhibit a fair amount of racial and ethnic diversity, as we saw earlier in this chapter. Children are more likely to live with only one parent among Latino and especially African American families than among white and Asian American families. Moreover, African American, Latino, and Native American children and their families are especially likely to live in poverty. As a result, they are at much greater risk for the many problems that children in poverty experience (see Chapter 2 “Poverty”).

Beyond these cold facts lie other racial and ethnic differences in family life (Wright, Mindel, Tran, & Habenstein, 2012). Studies of Latino and Asian American families find they have especially strong family bonds and loyalty. Extended families in both groups and among Native Americans are common, and these extended families have proven a valuable shield against the problems all three groups face because of their race/ethnicity and poverty.

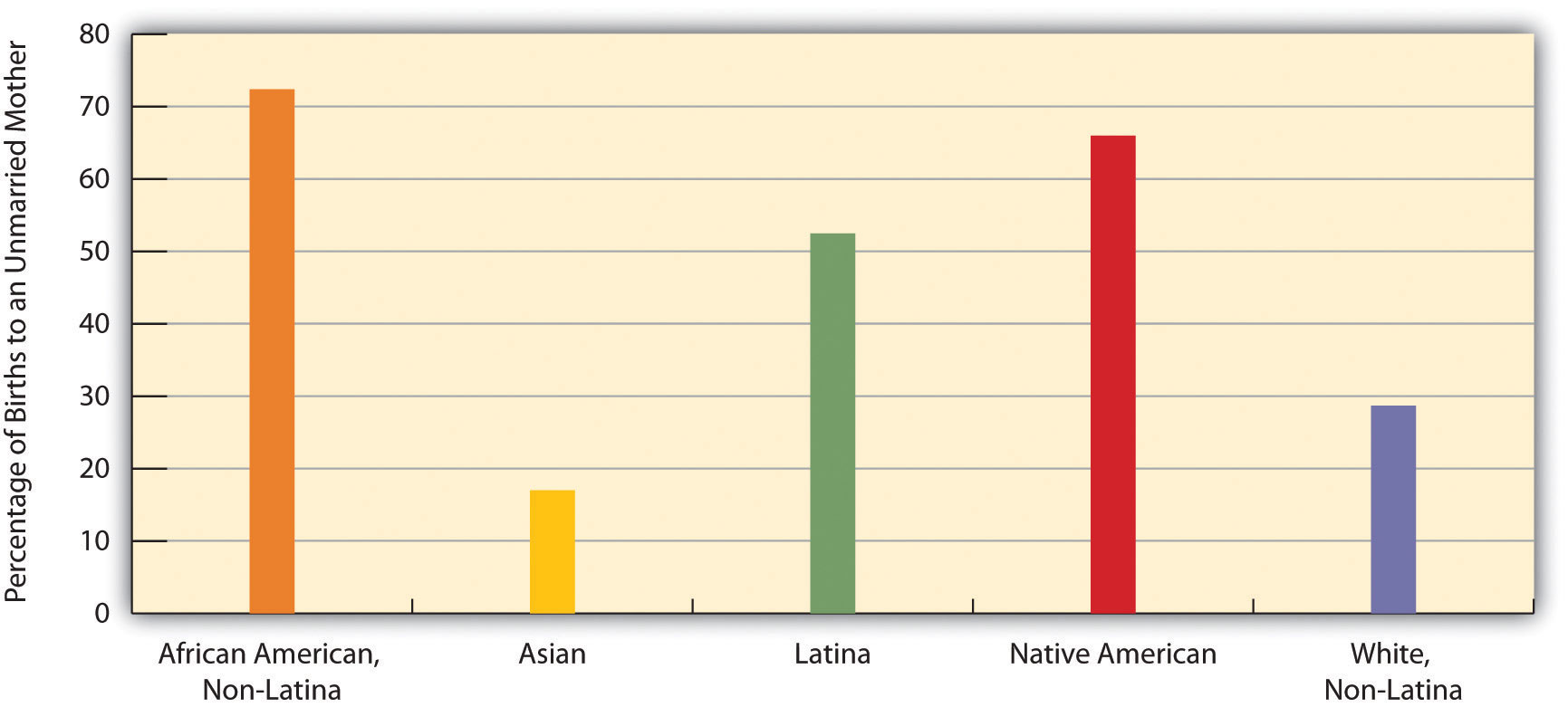

The status of the African American family has been the source of much controversy for several decades. Perhaps the major reason for this controversy is the large number of African American children living in single-parent households: Whereas 41 percent of all births are to unmarried women (up from 28 percent in 1990), such births account for 72 percent of all births to African American women (see Figure 10.5 “Percentage of Births to Unmarried Mothers, by Race/Ethnicity 2010”).

Figure 10.5 Percentage of Births to Unmarried Mothers, by Race/Ethnicity 2010

Source: Data from US Census Bureau. (2012). Statistical abstract of the United States: 2012. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab.

Many scholars attribute the high number of fatherless families among African Americans to the forcible separation of families during slavery and to the fact that so many young black males today are unemployed, in prison or jail, or facing other problems (Patterson, 1998). Some observers say this high number of fatherless families in turn contributes to African Americans’ poverty, crime, and other problems (Haskins, 2009). But other observers argue that this blame is misplaced to at least some extent. Extended families and strong female-headed households in the African American community, they say, have compensated for the absence of fathers (Willie & Reddick, 2010). The problems African Americans face, they add, stem to a large degree from their experience of racism, segregated neighborhoods, lack of job opportunities, and other structural difficulties (Sampson, 2009). Even if fatherless families contribute to these problems, these scholars say, these other factors play a larger role.

Family Violence

Although family violence has received much attention since the 1970s, families were violent long before scholars began studying family violence and the public began hearing about it. We can divide family violence into two types: violence against intimates (spouses, live-in partners, boyfriends, or girlfriends) and violence against children. (Violence against elders also occurs and was discussed in Chapter 6 “Aging and Ageism”.)

Violence against Intimates

Intimates commit violence against each other in many ways: they can hit with their fists, slap with an open hand, throw an object, push or shove, or use or threaten to use a weapon. When all these acts and others are combined, we find that much intimate violence occurs. While we can never be certain of the exact number of intimates who are attacked, the US Department of Justice estimates from its National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS) that about 509,000 acts of violence (2010 data) are committed annually by one intimate against another intimate; 80 percent of these acts are committed by men against women (Truman, 2011). Another national survey about a decade ago found that 22 percent of US women had been physically assaulted by a spouse or partner at some point in their lives (Tjaden & Thoennes, 1998). This figure, if still true, translates to more than 20 million women today. A national survey of Canadian women found that 29 percent had been attacked by a spouse or partner (Randall & Haskell, 1995). Taken together, these different figures all indicate that intimate partner violence is very common and affects millions of people.

According to some estimates, about one-fifth of US women have been assaulted by a spouse or partner at least once in their lives.

Neil Moralee – Not Defeated. – CC BY 2.0.

Some observers claim that husbands are just as likely as wives to be beaten by a spouse, and there is evidence that husbands experience an act of violence from their wives about as often as wives do from their husbands. Yet this “gender equivalence” argument has been roundly criticized. Although women do commit violence against husbands and boyfriends, their violence is less serious (e.g., a slap compared to using a fist) and usually in self-defense to their husbands’ violence. And although some studies find an equal number of violent acts committed by husbands and wives, other studies find much more violence committed by husbands (Johnson, 2006).

Why do men hit their wives, partners, and girlfriends? As with rape (see Chapter 4 “Gender Inequality”), sociologists answer this question by citing both structural and cultural factors. Structurally, women are the subordinate gender in a patriarchal society and, as such, are more likely to be victims of violence, whether it is rape or intimate violence. Intimate violence is more common in poor families, and economic inequality thus may lead men to take out their frustration over their poverty on their wives and girlfriends (Martin, Vieraitis, & Britto, 2006).

Cultural myths also help explain why men hit their wives and girlfriends (Gosselin, 2010). Many men continue to believe that their wives should not only love and honor them but also obey them, as the traditional marriage vow says. If they view their wives in this way, it becomes that much easier to hit them. In another myth, many people ask why women do not leave home if the hitting they suffer is really that bad; the implication is that the hitting cannot be that bad because they do not leave home. This reasoning ignores the fact that many women do try to leave home, which often angers their husbands and ironically puts the women more at risk for being hit, or they do not leave home because they have nowhere to go (Kim & Gray, 2008). As the news story that began this chapter discussed, battered women’s shelters are still few in number and can accommodate a woman and her children for only two or three weeks. Many battered women also have little money of their own and simply cannot afford to leave home. The belief that battering cannot be that bad if women hit by their husbands do not leave home ignores all these factors and is thus a myth that reinforces spousal violence against women. (See Note 10.15 “People Making a Difference” for a profile of the woman who started the first women’s shelter.)

People Making a Difference

The Founder of the First Battered Women’s Shelter

Sandra Ramos deserves our thanks because she founded the first known shelter for battered women in North America back in the late 1970s.

Her life changed one night in 1970 when she was only 28 years old and working as a waitress at a jazz club. One night a woman from her church in New Jersey came to her home seeking refuge from a man who was abusing her. Ramos took in the woman and her children and soon did the same with other abused women and their children. Within a few months, twenty-two women and children were living inside her house. “It was kind of chaotic,” recalls Maria, 47, the oldest of Ramos’s three children. “It was a small house; we didn’t have a lot of room. But she reaches out to people she sees suffering. She does everything in her power to help them.”

When authorities threatened to arrest Ramos if she did not remove all these people from her home, she conducted sit-ins and engaged in other actions to call attention to the women’s plight. She eventually won county funding to start the first women’s shelter.

Today Ramos leads a New Jersey nonprofit organization, Strengthen Our Sisters, that operates several shelters and halfway houses for battered women. Her first shelter and these later ones have housed thousands of women and children since the late 1970s, and at any one time today they house about 180 women and their children.

One woman whom Ramos helped was Geraldine Wright, who was born in the Dominican Republic. Wright says she owes Ramos a great debt. “Sandy makes you feel like, OK, you’re going through this, but it’s going to get better,” she says. “One of the best things I did for myself and my children was come to the shelter. She helped me feel strong, which I usually wasn’t. She helped me get a job here at the shelter so that I could find a place and pay the rent.”

Since that first woman knocked on her door in 1970, Sandra Ramos has worked unceasingly for the rights and welfare of abused women. She has fittingly been called “one of the nation’s most well-known and tireless advocates on behalf of battered women.” For more than forty years, Sandra Ramos has made a considerable difference.

Source: Llorente, 2009

Child Abuse

Child abuse takes many forms. Children can be physically or sexually assaulted, and they may also suffer from emotional abuse and practical neglect. Whatever form it takes, child abuse is a serious national problem.

It is especially difficult to know how much child abuse occurs. Infants obviously cannot talk, and toddlers and older children who are abused usually do not tell anyone about the abuse. They might not define it as abuse, they might be scared to tell on their parents, they might blame themselves for being abused, or they might not know whom they could talk to about their abuse. Whatever the reason, they usually remain silent, thus making it very difficult to know how much abuse takes place.

Government data estimate that about 800,000 children are abused or neglected each year. Because most children do not report their abuse or neglect, the actual number is probably much higher.

Jane Fox – Child Abuse mental – CC BY-ND 2.0.

Using information from child protective agencies throughout the country, the US Department of Health and Human Services estimates that almost 800,000 children (2008 data) are victims of child abuse and neglect annually (Administration on Children Youth and Families, 2010). This figure includes some 122,000 cases of physical abuse; 69,000 cases of sexual abuse; 539,000 cases of neglect; 55,000 cases of psychological maltreatment; and 17,000 cases of medical neglect. The total figure represents about 1 percent of all children under the age of 18. Obviously this is just the tip of the iceberg, as many cases of child abuse never become known. A 1994 Gallup poll asked adult respondents about physical abuse they suffered as children. Twelve percent said they had been abused (punched, kicked, or choked), yielding an estimate of 23 million adults in the United States who were physically abused as children (D. W. Moore, 1994). Some studies estimate that about 25 percent of girls and 10 percent of boys are sexually abused at least once before turning 18 (Garbarino, 1989). In a study of a random sample of women in Toronto, Canada, 42 percent said they had been sexually abused before turning 16 (Randall & Haskell, 1995). Whatever the true figure is, most child abuse is committed by parents, stepparents, and other people the children know, not by strangers.

Children and Our Future

Is Spanking a Good Idea?

As the text discusses, spanking underlies many episodes of child abuse. Nonetheless, many Americans approve of spanking. In the 2010 General Social Survey, 69 percent of respondents agreed that “it is sometimes necessary to discipline a child with a good, hard, spanking.” Reflecting this “spare the rod and spoil the child” belief, most parents have spanked their children. National survey evidence finds that two-thirds of parents of toddlers ages 19–35 months have spanked their child at least once, and one-fourth spank their child sometimes or often.

The reason that many people approve of spanking and that many parents spank is clear: They believe that spanking will teach a child a lesson and improve a child’s behavior and/or attitude. However, most child and parenting experts believe the opposite is true. When children are spanked, they say, and especially when they are spanked regularly, they are more likely to misbehave as a result. If so, spanking ironically produces the opposite result from what a parent intends.

Spanking has this effect for several reasons. First, it teaches children that they should behave to avoid being punished. This lesson makes children more likely to misbehave if they think they will not get caught, as they’d not learn to behave for its own sake. Second, spanking also teaches children that it is OK to hit someone to solve an interpersonal dispute and even to hit someone if you love her or him, because that is what spanking is all about. Third, children who are spanked may come to resent their parents and thus be more likely to misbehave because their bond with their parents weakens.

This harmful effect of spanking is especially likely when spanking is frequent. As Alan Kazin, a former president of the American Psychological Association (APA) explains, “Corporal punishment has really serious side effects. Children who are hit become more aggressive.” When spanking is rare, this effect may or may not occur, according to research on this issue, but this research also finds that other forms of discipline are as effective as a rare spanking in teaching a child to behave. This fact leads Kazin to say that even rare spanking should be avoided. “It suppresses [misbehavior] momentarily. But you haven’t really changed its probability of occurring. Physical punishment is not needed to change behavior. It’s just not needed.”

Sources: Berlin et al., 2009; Harder, 2007; Park, 2010; Regalado, Sareen, Inkelas, Wissow, & Halfon, 2004

Why does child abuse occur? Structurally speaking, children are another powerless group and, as such, are easy targets of violence. Moreover, the best evidence indicates that child abuse is more common in poorer families. The stress these families suffer from their poverty is thought to be a major reason for the child abuse occurring within them (Gosselin, 2010). As with spousal violence, then, economic inequality is partly to blame for child abuse. Cultural values and practices also matter. In a nation where spanking is common, it is inevitable that physical child abuse will occur, because there is a very thin line between a hard spanking and physical abuse: Not everyone defines a good, hard spanking in the same way. As two family violence scholars once noted, “Although most physical punishment [of children] does not turn into physical abuse, most physical abuse begins as ordinary physical punishment” (Wauchope & Straus, 1990, p. 147). (See Note 10.17 “Children and Our Future” for a further discussion of spanking.)

Abused children are much more likely than children who are not abused to end up with various developmental, psychological, and behavioral problems throughout their life course. In particular, they are more likely to be aggressive, to use alcohol and other drugs, to be anxious and depressed, and to get divorced if they marry (Trickett, Noll, & Putnam, 2011).

Key Takeaways

- The divorce rate rose for several reasons during the 1960s and 1970s but has generally leveled off since then.

- Divorce often lowers the psychological well-being of spouses and their children, but the consequences of divorce also depend on the level of contention in the marriage that has ended.

- Despite continuing controversy over the welfare of children whose mothers work outside the home, research indicates that children in high-quality day care fare better in cognitive development than those who stay at home.

- Violence between intimates is fairly common and stems from gender inequality, income inequality, and several cultural myths that minimize the harm that intimate violence causes.

- At least 800,000 children are abused or neglected each year in the United States. Because most abused children do not report the abuse, the number of cases of abuse and neglect is undoubtedly much higher.

For Your Review

- Think of someone you know (either yourself, a relative, or a friend) whose parents are divorced. Write a brief essay in which you discuss how the divorce affected this person.

- Do you think it is ever acceptable for a spouse to slap or hit another spouse? Why or why not?

References

Administration on Children Youth and Families. (2010). Child maltreatment 2008. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services.

Amato, P. R., & Hohmann-Marriott, B. (2007). A comparison of high- and low-distress marriages that end in divorce. Journal of Marriage & Family, 69(3), 621–638.

Apel, R., & Kaukinen, C. (2008). On the relationship between family structure and antisocial behavior: Parental cohabitation and blended households. Criminology, 46(1), 35–70.

Berlin, L. J., Ispa, J. M., Fine, M. A., Malone, P. S., Brooks-Gunn, J., Brady-Smith, C., et al. (2009). Correlates and consequences of spanking and verbal punishment for low-income white, African American, and Mexican American toddlers. Child Development, 80(5), 1403–1420.

Bernard, J. (1972). The future of marriage. New York, NY: Bantam.

Booth, A., Scott, M. E., & King, V. (2010). Father residence and adolescent problem behavior: Are youth always better off in two-parent families? Journal of Family Issues, 31(5), 585–605.

Brown, S. L. (2005). How cohabitation is reshaping American families. Contexts, 4(3), 33–37.

Brown, S. L., & Bulanda, J. R. (2008). Relationship violence in young adulthood: A comparison of daters, cohabitors, and marrieds. Social Science Research, 37(1), 73–87.

Cherlin, A. J. (2009). The origins of the ambivalent acceptance of divorce. Journal of Marriage & Family, 71(2), 226–229.

Clarke-Stewart, A., & Brentano, C. (2006). Divorce: Causes and consequences. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Coontz, S. (1997). The way we really are: Coming to terms with America’s changing families. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Demo, D. H., & Fine, M. A. (2010). Beyond the average divorce. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

DeNavas-Walt, C., Proctor, B. D., & Smith, J. C. (2011). Income, poverty, and health insurance coverage in the United States: 2010 (Current Population Reports, P60-239). Washington, DC: US Census Bureau.

Frech, A., & Williams, K. (2007). Depression and the psychological benefits of entering marriage. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 48, 149–163.

Gadalla, T. M. (2008). Gender differences in poverty rates after marital dissolution: A longitudinal study. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 49(3/4), 225–238.

Garbarino, J. (1989). The incidence and prevalence of child maltreatment. In L. Ohlin & M. Tonry (Eds.), Family violence (Vol. 11, pp. 219–261). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Glenn, N. D. (1997). A Critique of twenty family and marriage and the family textbooks. Family Relations, 46, 197–208.

Goodman, P. S. (2010, May 24). Cuts to child care subsidy thwart more job seekers. New York Times, p. A1.

Gosselin, D. K. (2010). Heavy hands: An introduction to the crimes of family violence (4th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Harder, B. (2007, February 19). Spanking: When parents lift their hands. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved from http://articles.latimes.com/2007/feb/19/health/he-spanking19.

Haskins, R. (2009). Moynihan was right: Now what? The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 621, 281–314.

Hiedemann, B., Suhomlinova, O., & O’Rand, A. M. (1998). Economic independence, economic status, and empty nest in midlife marital disruption. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 60, 219–231.

Hull, K. E., Meier, A., & Ortyl, T. (2012). The changing landscape of love and marriage. In D. Hartmann & C. Uggen (Eds.), The contexts reader (2nd ed., pp. 56–63). New York, NY: W. W. Norton.

Johnson, M. P. (2006). Conflict and control: Gender symmetry and asymmetry in domestic violence. Violence Against Women, 12, 1003–1018.

Jose, A., O’Leary, K. D., & Moyer, A. (2010). Does premarital cohabitation predict subsequent marital stability and marital quality? A meta-analysis. Journal of Marriage & Family, 72(1), 105–116.

Kim, J., & Gray, K. A. (2008). Leave or stay? Battered women’s decision after intimate partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 23(10), 1465–1482.

Kneip, T., & Bauer, G. (2009). Did unilateral divorce laws raise divorce rates in Western Europe? Journal of Marriage & Family, 71(3), 592–607.

Li, J.-C. A. (2010). Briefing paper: The impact of divorce on children’s behavior problems. In B. J. Risman (Ed.), Families as they really are (pp. 173–177). New York, NY: W. W. Norton.

Llorente, E. (2009). Strengthening her sisters. Retrieved November 2, 2011, from http://www.aarp.org/giving-back/volunteering/info-10-2009/strengthening_her_sisters.html.

Martin, K., Vieraitis, L. M., & Britto, S. (2006). Gender equality and women’s absolute status: A test of the feminist models of rape. Violence Against Women, 12, 321–339.

Moore, D. W. (1994, May). One in seven Americans victim of child abuse. The Gallup Poll Monthly, 18–22.

Moore, K. A., Kinghorn, A., & Bandy, T. (2011). Parental relationship quality and child outcomes across subgroups. Washington, DC: Child Trends.

Morin, R. (2010). The public renders a split verdict on changes in family structure. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center.

Park, A. (2010). The long-term effects of spanking. Time International (Atlantic Edition), 175(18), 95–95.

Parker-Pope, T. (2010, April 18). Is marriage good for your health? The New York Times Sunday Magazine, p. MM46.

Patterson, O. (1998). Rituals of blood: Consequences of slavery in two American centuries. Washington, DC: Civitas/CounterPoint.

Rabin, R. C. (2008, September 15). A consensus about day care: Quality counts. New York Times, p. A1.

Randall, M., & Haskell, L. (1995). Sexual violence in women’s lives: Findings from the Women’s Safety Project, a community-based survey. Violence Against Women, 1, 6–31.

Regalado, M., Sareen, H., Inkelas, M., Wissow, L. S., & Halfon, N. (2004). Parents’ discipline of young children: Results from the national survey of early childhood health. Pediatrics, 113, 1952–1958.

Rutter, V. E. (2010). The case for divorce. In B. J. Risman (Ed.), Families as they really are (pp. 159–169). New York, NY: W. W. Norton.

Sampson, R. J. (2009). Racial stratification and the durable tangle of neighborhood inequality. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 621, 260–280.

Schwartz, P. (1983). Length of day-care attendance and attachment behavior in eighteen-month-old infants. Child Development, 54, 1073–1078.

Teachman, J. (2008). Complex life course patterns and the risk of divorce in second marriages. Journal of Marriage & Family, 70(2), 294–305.

Theobald, D., & Farrington, D. P. (2011). Why do the crime-reducing effects of marriage vary with age? British Journal of Criminology, 51(1), 136–158.

Tjaden, P., & Thoennes, N. (1998). Prevalence, incidence, and consequences of violence against women: Findings from the national violence against women survey. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice.

Trickett, P. K., Noll, J. G., & Putnam, F. W. (2011). The impact of sexual abuse on female development: Lessons from a multigenerational, longitudinal research study. Development and Psychopathology, 23(2), 453–476.

Truman, J. L. (2011). Criminal victimization, 2010. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics.

Waite, L. J., Luo, Y., & Lewin, A. C. (2009). Marital happiness and marital stability: Consequences for psychological well-being. Social Science Research, 38(1), 201–212

Wauchope, B., & Straus, M. A. (1990). Physical punishment and physical abuse of American children: Incidence rates by age, gender, and occupational class. In M. A. Straus & R. J. Gelles (Eds.), Physical violence in American families: Risk factors and adaptations to violence in 8,145 families (pp. 133–148). New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Books.

Wilcox, W. B. (Ed.). (2010). The state of our unions 2010: Marriage in America. Charlottesville, VA: National Marriage Project.

Willie, C. V., & Reddick, R. J. (2010). A new look at black families (6th ed.). Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Wright, R. H., Jr., Mindel, C. H., Tran, T. V., & Habenstein, R. W. (Eds.). (2012). Ethnic families in America: Patterns and variations (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.