83

Learning Objectives

- Explain why terrorism is difficult to define.

- List the major types of terrorism.

- Evaluate the law enforcement and structural-reform approaches for dealing with terrorism.

The 9/11 attacks spawned an immense national security network and prompted the expenditure of more than $3 trillion on the war against terrorism.

Michael Foran – 9/11 WTC 32 – CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Terrorism is hardly a new phenomenon, but Americans became horrifyingly familiar with it on September 11, 2001. The 9/11 attacks remain in the nation’s consciousness, and many readers may know someone who died on that terrible day. The attacks also spawned a vast national security network that now reaches into almost every aspect of American life. This network is so secretive, so huge, and so expensive that no one really knows precisely how large it is or how much it costs (Priest & Arkin, 2010). However, it is thought to include 1,200 government organizations, 1,900 private companies, and almost 900,000 people with security clearances (Applebaum, 2011). The United States has spent an estimated $3 trillion since 9/11 on the war on terrorism, including more than $1 trillion on the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan whose relevance for terrorism has been sharply questioned. Questions of how best to deal with terrorism continue to be debated, and there are few, if any, easy answers to these questions.

Not surprisingly, sociologists and other scholars have written many articles and books about terrorism. This section draws on their work to discuss the definition of terrorism, the major types of terrorism, explanations for terrorism, and strategies for dealing with terrorism. An understanding of all these issues is essential to make sense of the concern and controversy about terrorism that exists throughout the world today.

Defining Terrorism

There is an old saying that “one person’s freedom fighter is another person’s terrorist.” This saying indicates some of the problems in defining terrorism precisely. Some years ago, the Irish Republican Army (IRA) waged a campaign of terrorism against the British government and its people as part of its effort to drive the British out of Northern Ireland. Many people in Northern Ireland and elsewhere hailed IRA members as freedom fighters, while many other people condemned them as cowardly terrorists. Although most of the world labeled the 9/11 attacks as terrorism, some individuals applauded them as acts of heroism. These examples indicate that there is only a thin line, if any, between terrorism on the one hand and freedom fighting and heroism on the other hand. Just as beauty is in the eyes of the beholder, so is terrorism. The same type of action is either terrorism or freedom fighting, depending on who is characterizing the action.

Although dozens of definitions of terrorism exist, most take into account what are widely regarded as the three defining features of terrorism: (a) the use of violence; (b) the goal of making people afraid; and (c) the desire for political, social, economic, and/or cultural change. A popular definition by political scientist Ted Robert Gurr (1989, p. 201) captures these features: “The use of unexpected violence to intimidate or coerce people in the pursuit of political or social objectives.”

As the attacks on 9/11 remind us, terrorism involves the use of indiscriminate violence to instill fear in a population and thereby win certain political, economic, or social objectives.

Cliff – September 11th, 2011 – CC BY 2.0.

Types of Terrorism

When we think about this definition, 9/11 certainly comes to mind, but there are, in fact, several kinds of terrorism—based on the identity of the actors and targets of terrorism—to which this definition applies. A typology of terrorism, again by Gurr (1989), is popular: (a) vigilante terrorism, (b) insurgent terrorism, (c) transnational (or international) terrorism, and (d) state terrorism. Table 16.3 “Types of Terrorism” summarizes these four types.

Table 16.3 Types of Terrorism

| Vigilante terrorism | Violence committed by private citizens against other private citizens. |

| Insurgent terrorism | Violence committed by private citizens against their own government or against businesses and institutions seen as representing the “establishment.” |

| Transnational terrorism | Violence committed by citizens of one nation against targets in another nation. |

| State terrorism | Violence committed by a government against its own citizens. |

Vigilante terrorism is committed by private citizens against other private citizens. Sometimes the motivation is racial, ethnic, religious, or other hatred, and sometimes the motivation is to resist social change. The violence of racist groups like the Ku Klux Klan was vigilante terrorism, as was the violence used by white Europeans against Native Americans from the 1600s through the 1800s. What we now call “hate crime” is a contemporary example of vigilante terrorism.

Insurgent terrorism is committed by private citizens against their own government or against businesses and institutions seen as representing the “establishment.” Insurgent terrorism is committed by both left-wing groups and right-wing groups and thus has no political connotation. US history is filled with insurgent terrorism, starting with some of the actions the colonists waged against British forces before and during the American Revolution, when “the meanest and most squalid sort of violence was put to the service of revolutionary ideals and objectives” (Brown, 1989, p. 25). An example here is tarring and feathering: hot tar and then feathers were smeared over the unclothed bodies of Tories. Some of the labor violence committed after the Civil War also falls under the category of insurgent terrorism, as does some of the violence committed by left-wing groups during the 1960s and 1970s. A relatively recent example of right-wing insurgent terrorism is the infamous 1995 bombing of the federal building in Oklahoma City by Timothy McVeigh and Terry Nichols that killed 168 people.

Transnational terrorism is committed by the citizens of one nation against targets in another nation. This is the type that has most concerned Americans at least since 9/11, yet 9/11 was not the first time Americans had been killed by international terrorism. A decade earlier, a truck bombing at the World Trade Center killed six people and injured more than 1,000 others. In 1988, 189 Americans were among the 259 passengers and crew who died when a plane bound for New York exploded over Lockerbie, Scotland; agents from Libya were widely thought to have planted the bomb. Despite all these American deaths, transnational terrorism has actually been much more common in several other nations: London, Madrid, and various cities in the Middle East have often been the targets of international terrorists.

State terrorism involves violence by a government that is meant to frighten its own citizens and thereby stifle their dissent. State terrorism may involve mass murder, assassinations, and torture. Whatever its form, state terrorism has killed and injured more people than all the other kinds of terrorism combined (Gareau, 2010). Genocide, of course is the most deadly type of state terrorism, but state terrorism also occurs on a smaller scale. As just one example, the violent response of Southern white law enforcement officers to the civil rights protests of the 1960s amounted to state terrorism, as officers murdered or beat hundreds of activists during this period. Although state terrorism is usually linked to authoritarian regimes, many observers say the US government also engaged in state terror during the nineteenth century, when US troops killed thousands of Native Americans (D. A. Brown, 2009).

Explaining Terrorism

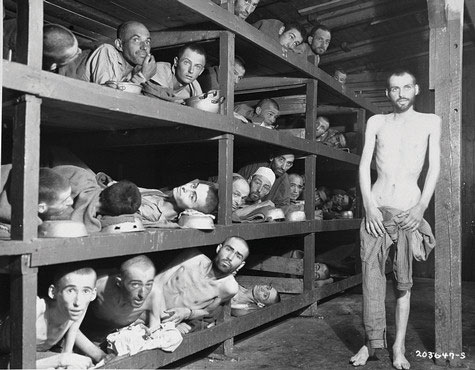

Genocide is the most deadly type of state terrorism. The Nazi holocaust killed some 6 million Jews and 6 million other people.

Wikimedia Commons – CC BY 2.0.

Why does terrorism occur? It is easy to assume that terrorists must have psychological problems that lead them to have sadistic personalities, and that they are simply acting irrationally and impulsively. However, most researchers agree that terrorists are psychologically normal despite their murderous violence and, in fact, are little different from other types of individuals who use violence for political ends. As one scholar observed, “Most terrorists are no more or less fanatical than the young men who charged into Union cannon fire at Gettysburg or those who parachuted behind German lines into France. They are no more or less cruel and coldblooded than the Resistance fighters who executed Nazi officials and collaborators in Europe, or the American GI’s ordered to ‘pacify’ Vietnamese villages” (Rubenstein, 1987, p. 5).

Contemporary terrorists tend to come from well-to-do families and to be well-educated themselves; ironically, their social backgrounds are much more advantaged in these respects than are those of common street criminals, despite the violence they commit.

If terrorism cannot be said to stem from individuals’ psychological problems, then what are its roots? In answering this question, many scholars say that terrorism has structural roots. In this view, terrorism is a rational response, no matter how horrible it may be, to perceived grievances regarding economic, social, and/or political conditions (White, 2012). The heads of the US 9/11 Commission, which examined the terrorist attacks of that day, reflected this view in the following assessment: “We face a rising tide of radicalization and rage in the Muslim world—a trend to which our own actions have contributed. The enduring threat is not Osama bin Laden but young Muslims with no jobs and no hope, who are angry with their own governments and increasingly see the United States as an enemy of Islam” (Kean & Hamilton, 2007, p. B1). As this assessment indicates, structural conditions do not justify terrorism, of course, but they do help explain why some individuals decide to commit it.

The Impact of Terrorism

The major impact of terrorism is apparent from its definition, which emphasizes public fear and intimidation. Terrorism can work, or so terrorists believe, precisely because it instills fear and intimidation. Anyone who might have happened to be in or near New York City on 9/11 will always remember how terrified the local populace was to hear of the attacks and the fears that remained with them for the days and weeks that followed.

Hardly anyone likes standing in the long airport security lines that are a result of the 9/11 attacks. Some experts say that certain airport security measures are an unneeded response to these attacks.

James Emery – ATL Delta’s baggage check – CC BY 2.0.

Another significant impact of terrorism is the response to it. As mentioned earlier, the 9/11 attacks led the United States to develop an immense national security network that defies description and expense, as well as the Patriot Act and other measures that some say threaten civil liberties; to start the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan; and to spend more than $3 trillion in just one decade on homeland security and the war against terrorism. Airport security increased, and Americans have grown accustomed to having to take off their shoes, display their liquids and gels in containers limited to three ounces, and stand in long security lines as they try to catch their planes.

People critical of these effects say that the “terrorists won,” and, for better or worse, they may be correct. As one columnist wrote on the tenth anniversary of 9/11, “And yet, 10 years after 9/11, it’s clear that the ‘war on terror’ was far too narrow a prism through which to see the planet. And the price we paid to fight it was far too high” (Applebaum, 2011, p. A17). In this columnist’s opinion, the war on terror imposed huge domestic costs on the United States; it diverted US attention away from important issues regarding China, Latin America, and Africa; it aligned the United States with authoritarian regimes in the Middle East even though their authoritarianism helps inspire Islamic terrorism; and it diverted attention away from the need to invest in the American infrastructure: schools, roads, bridges, and medical and other research. In short, the columnist concluded, “in making Islamic terrorism our central priority—at times our only priority—we ignored the economic, environmental and political concerns of the rest of the globe. Worse, we pushed aside our economic, environmental and political problems until they became too great to be ignored” (Applebaum, 2011, p. A17).

To critics like this columnist, the threat to Americans of terrorism is “over-hyped” (Holland, 2011b). They acknowledge the 9/11 tragedy and the real fears of Americans, but they also point out that in the years since 9/11, the number of Americans killed in car accidents, by air pollution, by homicide, or even by dog bites or lightning strikes has greatly exceeded the number of Americans killed by terrorism. They add that the threat is overhyped because defense industry lobbyists profit from overhyping it and because politicians do not wish to be seen as “weak on terror.” And they also worry that the war on terror has been motivated by and also contributed to prejudice against Muslims (Kurzman, 2011).

Key Takeaways

- Terrorism involves the use of intimidating violence to achieve political ends. Whether a given act of violence is perceived as terrorism or as freedom fighting often depends on whether someone approves of the goal of the violence.

- Several types of terrorism exist. The 9/11 attacks fall into the transnational terrorism category.

For Your Review

- Do you think the US response to the 9/11 attacks has been appropriate, or do you think it has been too overdone? Explain your answer.

- Do you agree with the view that structural problems help explain Middle Eastern terrorism? Why or why not?

References

Applebaum, A. (2011, September 2). The price we paid for the war on terror. The Washington Post, p. A17.

Brown, D. A. (2009). Bury my heart at Wounded Knee: An Indian history of the American west. New York, NY: Sterling Innovation.

Brown, R. M. (1989). Historical patterns of violence. In T. R. Gurr (Ed.), Violence in America: Protest, rebellion, reform (Vol. 2, pp. 23–61). Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Gareau, F. H. (2010). State terrorism and the United States: From counterinsurgency to the war on terrorism. Atlanta, GA: Clarity Press.

Gurr, T. R. (1989). Political terrorism: Historical antecedents and contemporary trends. In T. R. Gurr (Ed.), Violence in America: Protest, rebellion, reform (Vol. 2, pp. 201–230). Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Holland, J. (2011, September 14). How fearmongering over terrorism is endangering American communities. AlterNet. Retrieved from http://www.alternet.org/story/152403/how_fearmongering_over_terrorism_is_skewing_our_priorities_and_putting_us _all_at_risk_?page=entire.

Kean, T. H., & Hamilton, L. H. (2007, September 9). Are we safer today? The Washington Post, p. B1.

Kurzman, C. (2011, July 31). Where are all the Islamic terrorists? The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved from http://chronicle.com/article/Where-Are-All-the-Islamic/128443/?sid=cr&utm_source=cr&utm_medium=en.

Priest, D., & Arkin, W. M. (2010, July 20). A hidden world, growing beyond control. The Washington Post, p. A1.

Rubenstein, R. E. (1987). Alchemists of revolution: Terrorism in the modern world. New York, NY: Basic Books.

White, J. R. (2012). Terrorism and homeland security: An introduction (7th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.