Black Greek Life

Black Greek Letter organizations have served as significant institutions for Black students on campuses across the US. A study produced in 2008 noted that Black fraternities and sororities “…facilitated the cultural adjustment and membership of minority student participants by serving as sources of cultural familiarity, vehicles for cultural expression and advocacy, and venues for cultural validation.”1 Another study in 2001 notes that “minority students perceive that membership within multicultural organizations provides them greater opportunities to share their skills and talents with the African American community.”2

These two different studies conclude that Black Greek organizations provide much needed support to Black students at Predominantly White Universities, helping Black students to integrate at the university while also improving academic success and student retention. The vital importance, then, of these organizations to Black students on campuses, such as can be seen with cultural centers and student unions, is in their (Black Greek organizations) ability to provide an inclusive and safe space for students of color. Another study in 2006 further noted the improvement of Black students due to the Greek organizations, concluding that enrollment in these entities provided Black students with a better college experience that then encouraged them to reach out to other Black students not in their fraternity.3

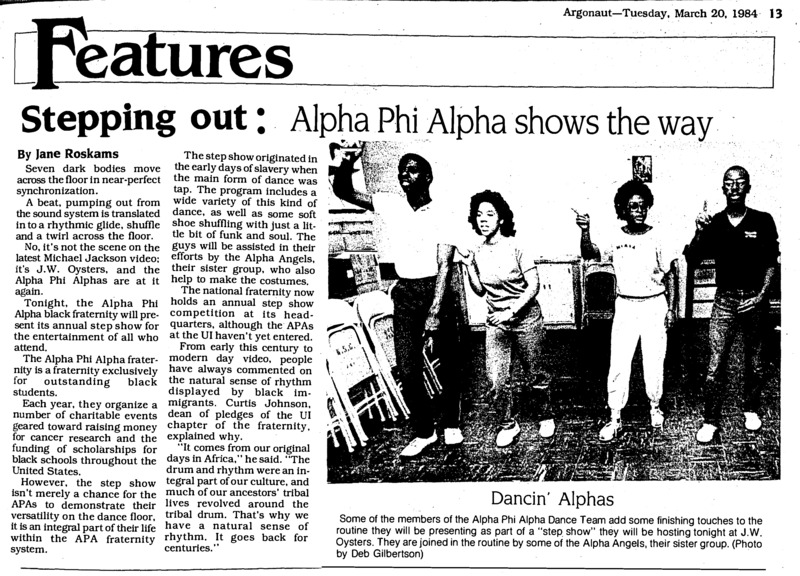

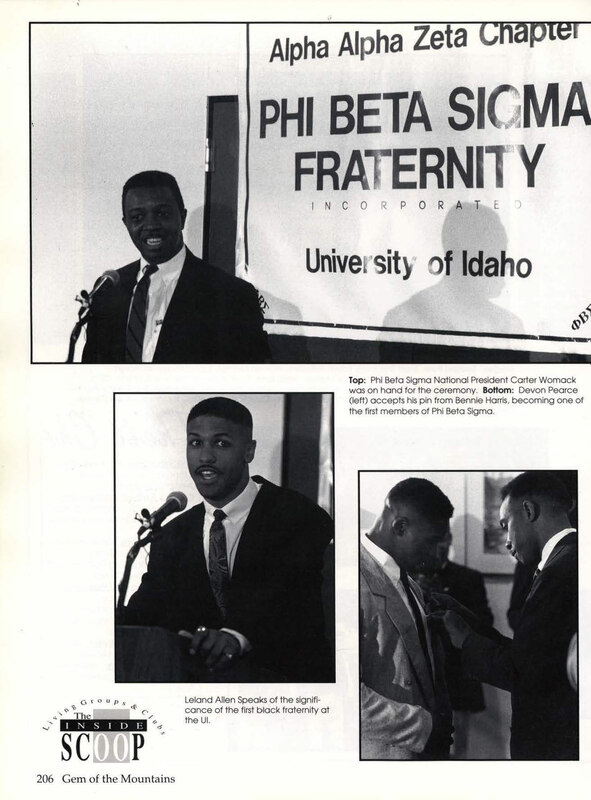

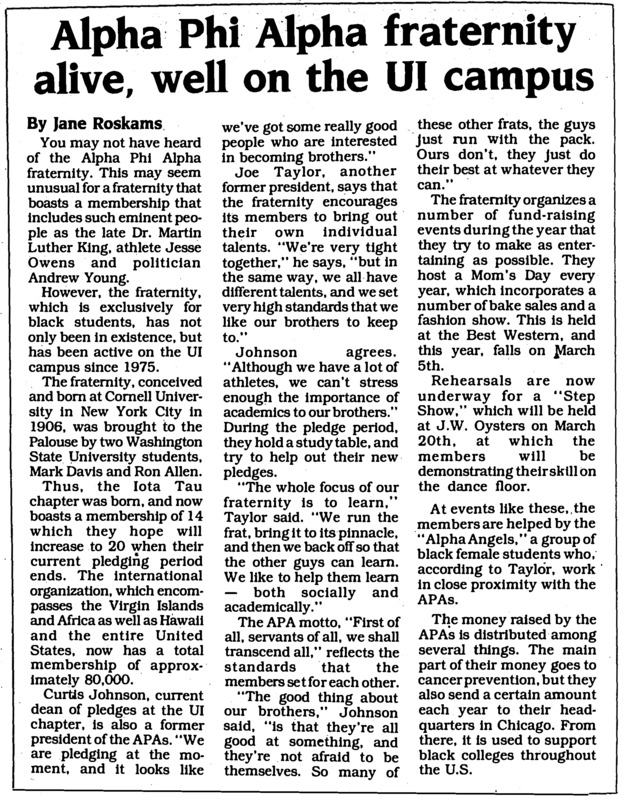

The development of Black fraternities could be seen at least in part as resulting from the success of student-athletes like those earlier described. Their success encouraged more Black students to enroll at the University of Idaho through the athletics department and also encouraged the University to step up Black recruitment. The growth of Black students on campus can be seen in the two Black fraternities that popped up on campus: a chapter of the Alpha Phi Alpha in 19754 and the Alpha Alpha Zeta chapter of the Phi Beta Sigma fraternity in 1992.5 There was also the “Alpha Angels,” who were the sorority chapter of Alpha Phi Alpha and who helped the fraternity with events.6 Sadly, all three of these chapters are no longer active.

Notes

- Samuel Museus, “The Role of Ethnic Student Organizations in Fostering African American and Asian American Students’ Cultural Adjustment and Membership at Predominantly White Institutions,” Journal of College Student Development, no. 6 (2008): 576, https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.0.0039. ↩

- E. Michael Sutton and Walter Kimbrough, “Trends in Black Student Involvement,” NASPA Journal, no. 1 (2001): 31-32, https://doi.org/10.2202/1949-6605.1160. ↩

- Stephanie McClure, “Voluntary Association Membership: Black Greek Men on a Predominantly White Campus,” Journal of Higher Education, no. 6 (2006): 1047, https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2006.11778955. ↩

- Jane Roskams, “Stepping Out: Alpha Phi Alpha Shows the Way,” Argonaut, Mar. 20, 1984. ↩

- University of Idaho, Gem of the Mountains, (Moscow, ID: 1992), 210-211, University of Idaho Digital Archives, https://digital.lib.uidaho.edu/digital/collection/gem/id/36380/rec/46, accessed on June 4, 2022. ↩

- Jane Roskams, “Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity Alive, Well on the UI campus,” Argonaut, Feb. 24, 1984. ↩