Black Studies at U of I

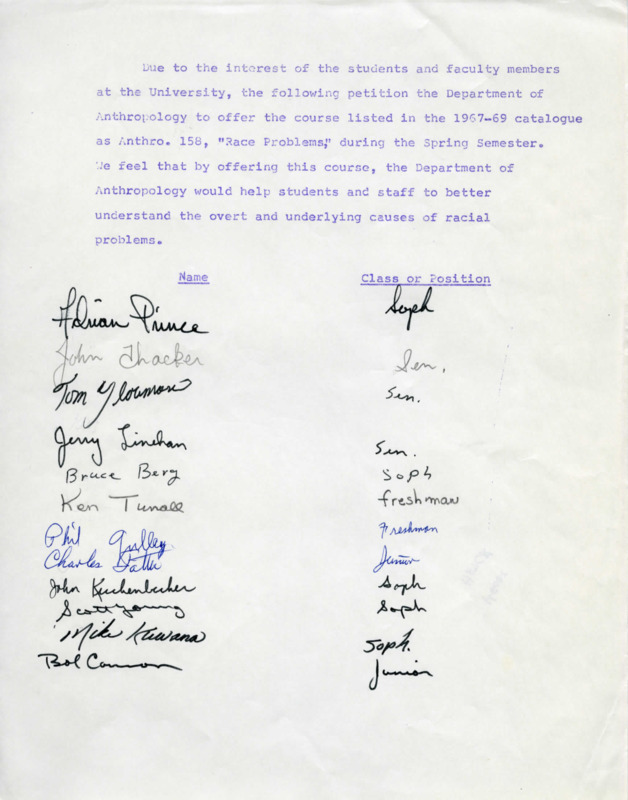

The impacts of the University of Idaho’s recruitment were felt further into the late 1960s as several students began floating around petitions for the adoption of Black studies courses. The first of these was a petition in 1966 for the adoption of Anthropology 158, “Race Problems,” which was aimed to teach university students about the underlying causes that gave way to racial problems.1 This petition did not have many signatures, and it seems that there were no real actions taken by the University from it, but it would serve as a base for later petitions.

Around this time, the fight for Black Studies programs had grown quite large, with the Civil Rights movement pushing for greater inclusivity at universities. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 had made it so that educational institutes could not ban anyone on account of the color of their skin, inspiring strikes such as the ones at the San Francisco State College in 1968 and 1969 that resulted in many new rights for Black students and other students of color.2 As such, these changes quickly brought more Black students to universities and further increased Black voices on campuses. The fight for Black studies programs on campuses increased further after the murders of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X, with Black students insisting that Black studies programs were necessary in order to improve their situation and to educate the White students.

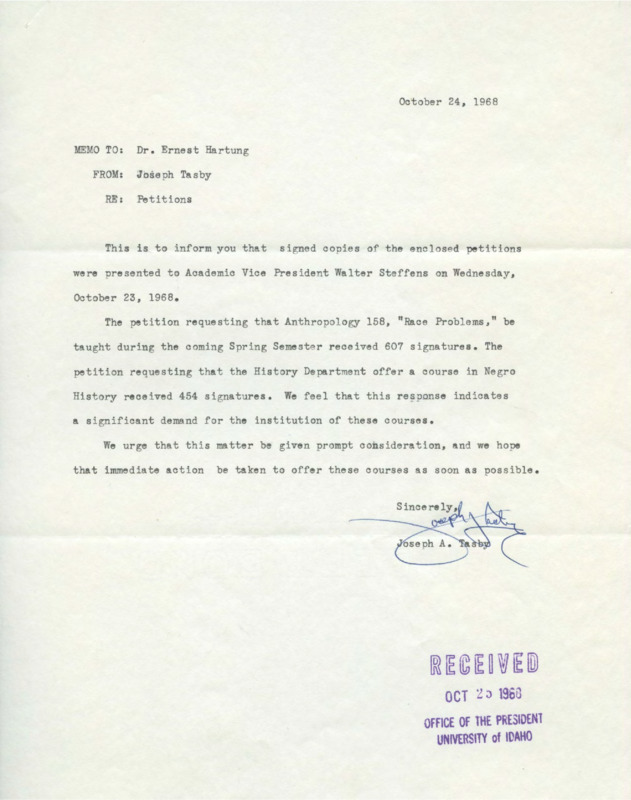

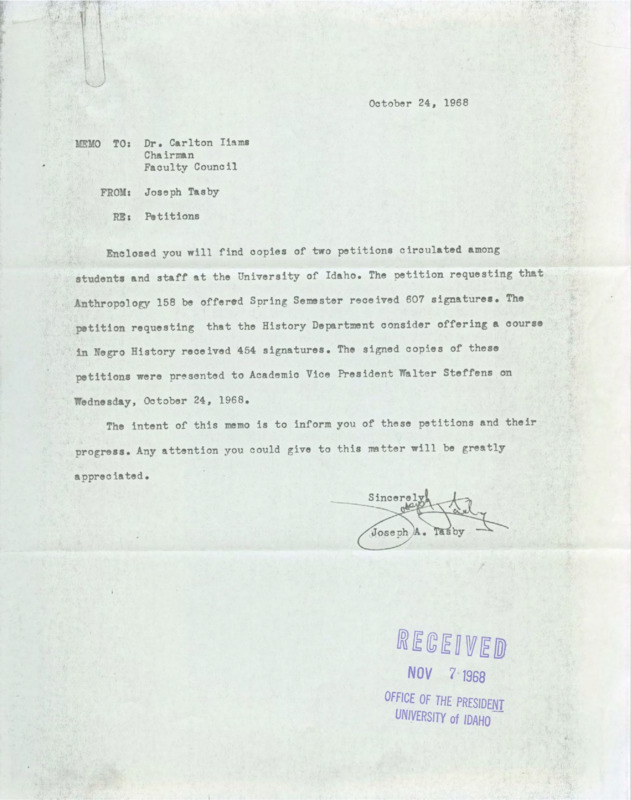

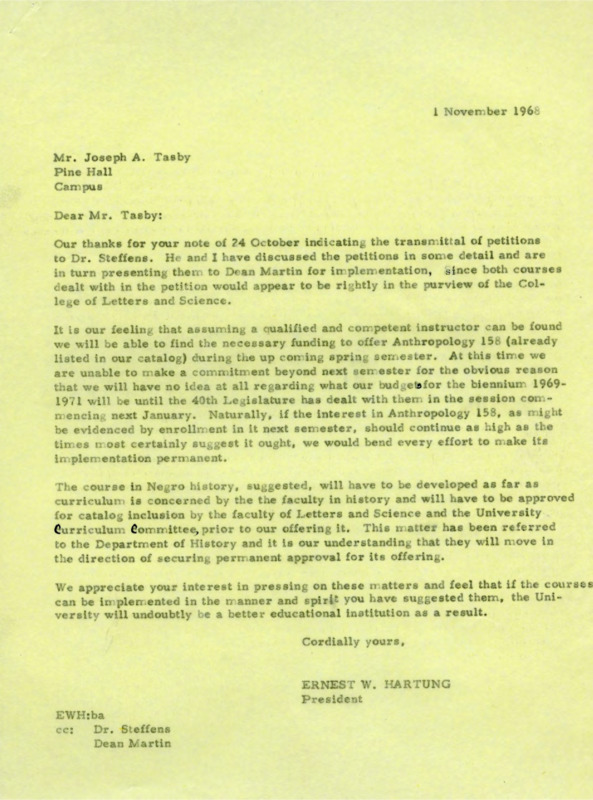

In 1968, another set of petitions was distributed to the student population by Joseph A. Tasby, a Black student-athlete. These sets of petitions received much more attention than the one in 1966, garnering over 400 signatures and creating “noise” in the history department and the President’s office.3 The petitions were intended to re-activate the Anthropology 158 course and to create a new Black history course titled “The Negro in America” for the 1969 school year.4 These petitions, as mentioned above, made a commotion within the faculty ranks of the University, and as such, President Ernest Hartung responded to Tasby by stating that if the University could implement the courses, then it would make the University undoubtedly a better educational institute.5

Despite this backing from President Hartung, the History Department was unsure of how to proceed with implementing a course focused on the Black community at the University. One argument brought up was that neither Jews nor women had their own specific course, and Black history was already being taught in other subjects, which would lead to redundancy if the new course was implemented. There was also the issue of recruiting an instructor, as the petitions had called for a Black history course to be taught by a Black professor; however, the University of Idaho did have issues in the past when it came to recruiting Black professors. This was due to several reasons, the biggest being the perception that not many Black professors were interested in coming to the University of Idaho. These issues combined, leading to a stalemate in 1969 with no ground being broken and the creation of a Black history course being left up in the air.

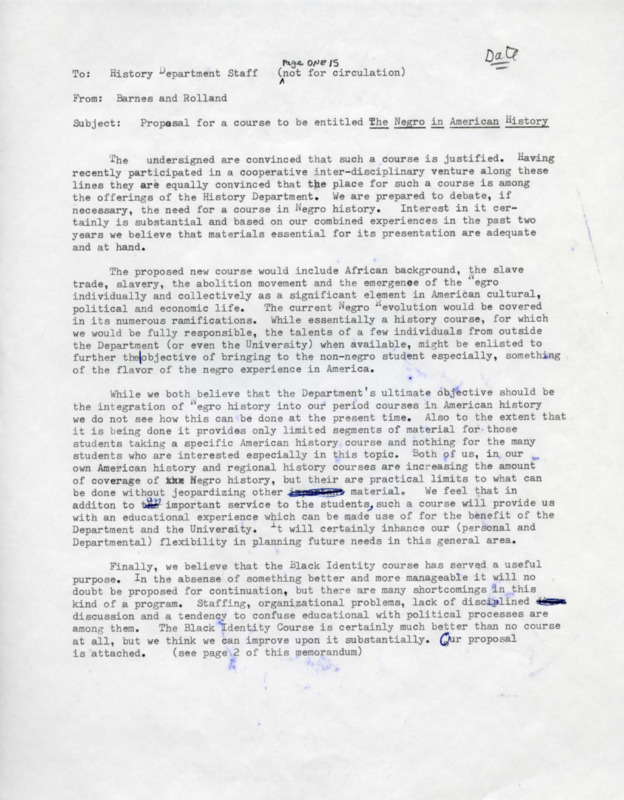

However, this would not remain the case as Professors Siegfried B. Rolland and Willard Barnes, who both happened to be White, would restate the issue in memorandums they wrote in 1970.6 These memorandums argued for the case of having such a course as well as proposed the intended structure of said course.

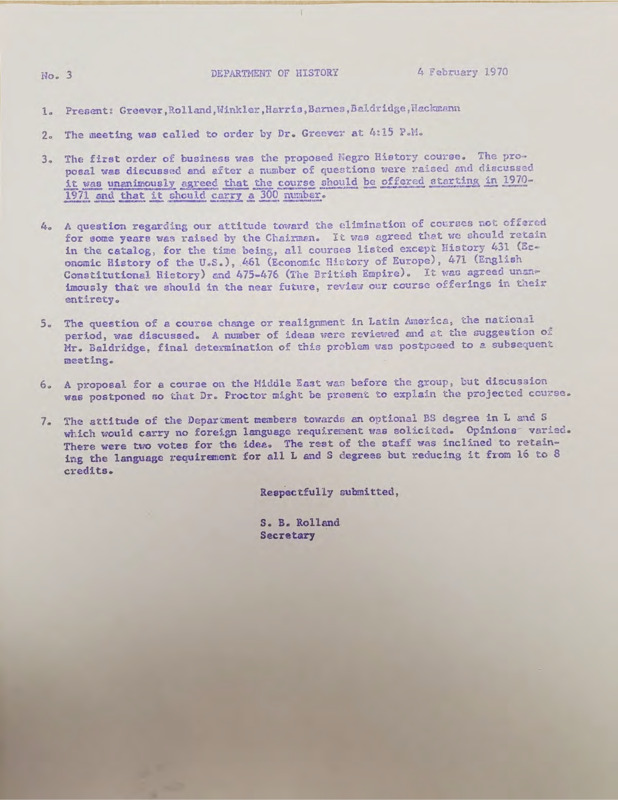

Although senior administrators would have to approve the course, students and faculty were the driving forces behind this initiative. This is why racially and ethnically diverse administrators are important, something that will be discussed later on in the document. This is a key issue that will reappear throughout the Black history at the University of Idaho, with faculty taking matters into their hands to create programs designed to educate and promote Black culture on campus. With the work done by Professors Rolland and Barnes, the discussion surrounding the implementation of these courses was brought back to light in early 1970, when a meeting was held and it was decided that Black courses would be implemented for the 1970-1971 catalog year.7

The implementation of the “The Negro in America” history course was instrumental in the history of Black studies as it paved the way for more courses to be implemented, and it also saw to it that the University focused more on educating about Black history on campus. However, it should still be noted that these courses were handled almost exclusively by the professors within their respective departments instead of senior management for the University of Idaho. The efforts of Drs. Rolland and Barnes, the student population, and the Washington State University sociology department’s Black faculty (most notably Ken Johnson) saw to it that these courses were implemented. However, it would be an oversight not mention the efforts of Professor Jack Davis and his work in the Black literature course.

Professor Jack Davis joined the English Department at the University of Idaho in 1967 after graduating from the University of New Mexico with his PhD in American studies. In 1970, under pressure from the student body at the University, Professor Davis took up the English 327 course “Black Literature,” and he also began instructing a Native American literature course. At this time, Professor Davis was one of the only faculty members of color at the University of Idaho (he identified as Native American), and as such, his role in these courses shows a substantial shift in University policy. On top of teaching these new courses, he was also appointed as the first coordinator for the Black Studies Program and the American Indian Studies Program at the University.8

Dr. Davis’s work at the University, together with his presence, served as auspicious signs that the environment was beginning to change and that students and faculty of color were more of a priority than they had been in previous years. The policy change indicated here implies that there was some support for the establishment of a Black studies program at the University of Idaho.

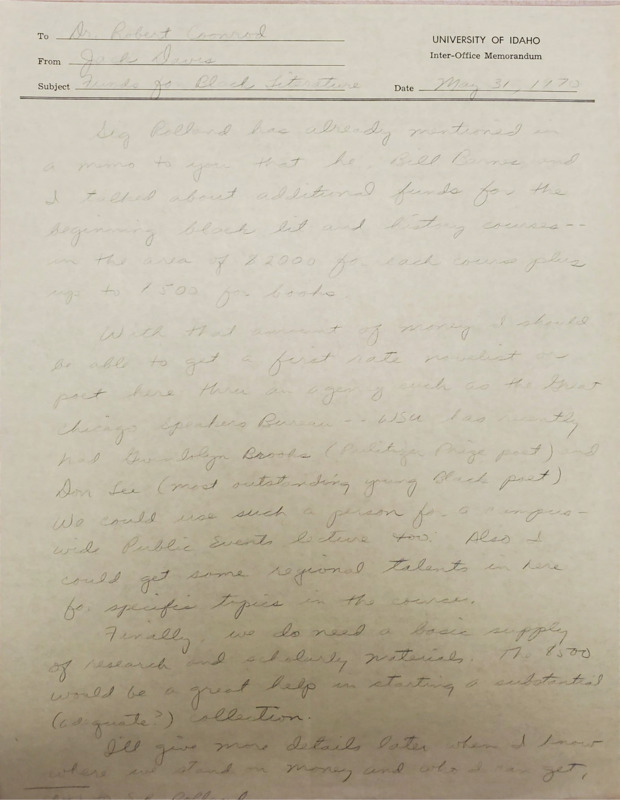

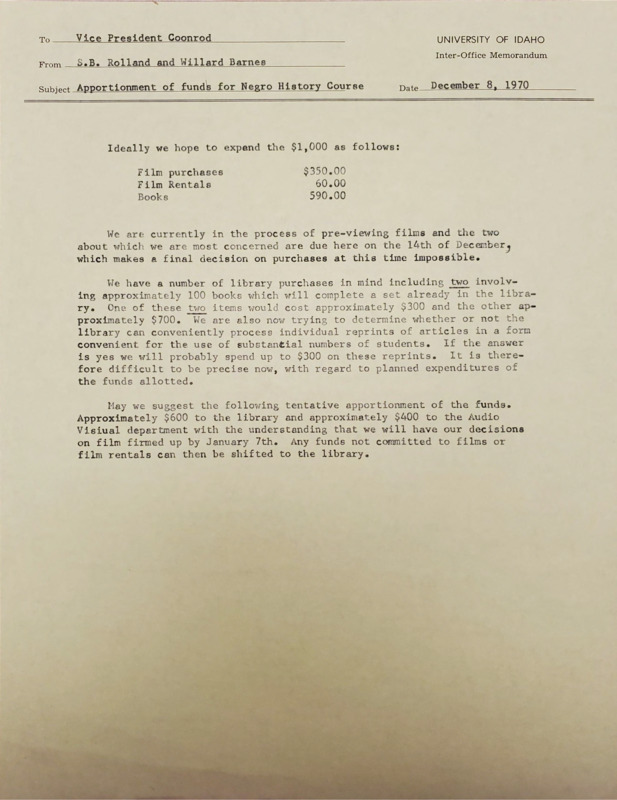

Late in 1970, several drafts and memorandums were written in the discussion of funds for the “The Negro in America” history course and the Black literature course. These memorandums were sent mostly between Rolland and Robert Coonrod, the vice president of academics at the time, and Joe Watts, the University’s business manager at the time. One of these memorandums, from Coonrod to Davis, discussed the talks Coonrod, Rolland, and Barnes had held about the optimal funds being $2,000 for the initial course and an additional $1,500 for books.9 Though these initial funding points had been talked over, the level of funding asked for was not initially met, and when further funded, the amount was still lower than the $3,500 asked for.

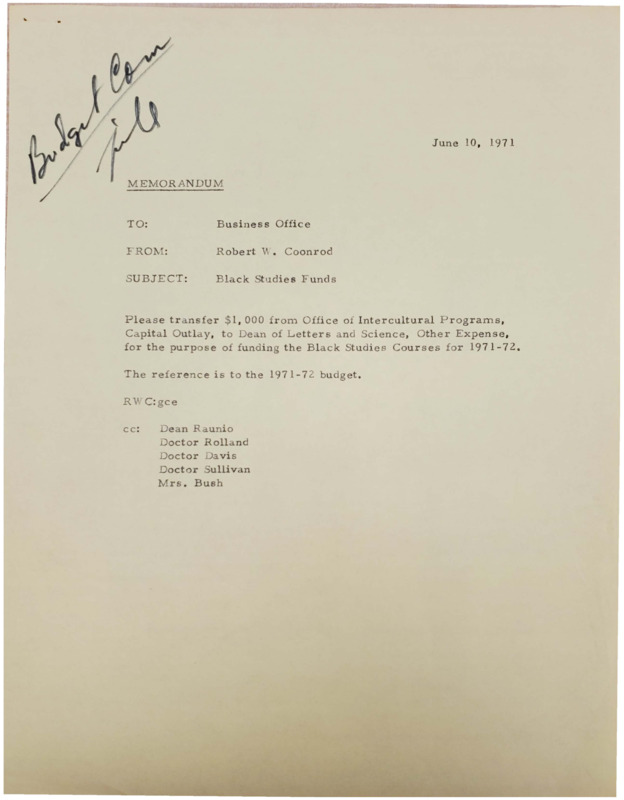

The starting budget for the “The Negro in America” history course was $1,000, though Dr. Rolland asked that the price be raised by $600 to cover film purchases and rentals.10 Dr. Davis asked for $1,500 for the Black literature course, though he argued that $2,000 would be more ideal for covering speakers, films, and books.11 Funding would continue with more money shifted from departments like the Office of Intercultural Programs to continue to grow these courses.12 From there, the Black studies program at the University was able to grow further and add additional classes that had not been offered before.

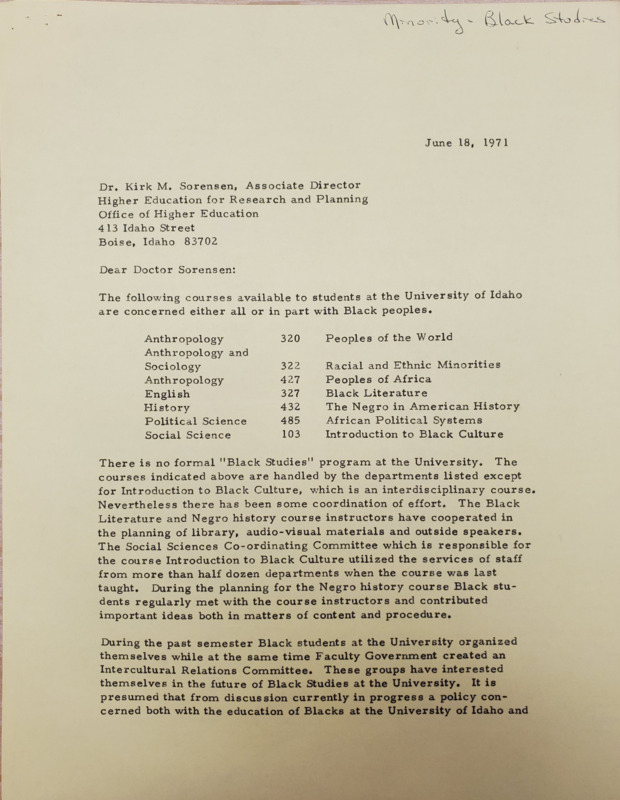

By the summer of 1971, the two-course program had added another five courses dealing with different aspects of Black history and culture around the world. The five courses added were maintained within the College of Letters and Arts in concert with the “The Negro in America” history course and Black literature, as this was where the main pressure from faculty on this matter had been. The five courses added were Anthropology 320 (Peoples of the World), Anthropology and Sociology 322 (Racial and Ethnic Minorities), Anthropology 427 (Peoples of Africa), Political Science 485 (African Political Systems), and Social Science 103 (Introduction to Black Culture).13 The addition of more courses shows that the initiative to help diversify the learning culture of the University was present and that the student population was also interested in learning more about Black history and culture.

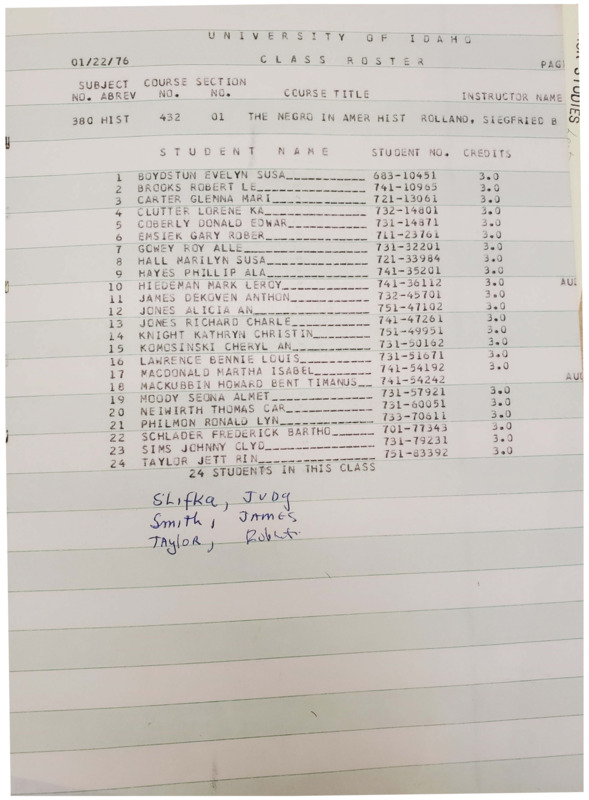

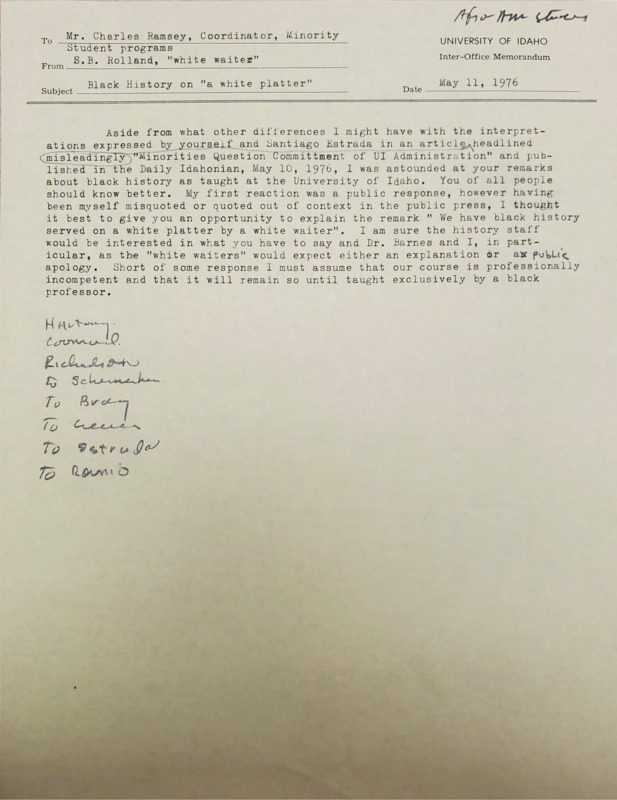

The support for the Black Studies Program can be seen in the rosters of “The Negro in America” history course for the spring of 1976, which was full.14 This would fit with the enthusiasm for Black studies of the 1970s, in which many universities adopted Black studies programs as the Civil Rights movement progressed.15 This led to issues with many of these courses as they were taught almost exclusively by White professors, excluding Jack Davis’s Black literature course. which resulted in perceptions that instructors of these courses did not have the correct experience to be teaching about Black history so much so that there was eventually a controversy later in the program’s life regarding this fact as Black faculty were annoyed with being taught “Black History on a White Platter.”16

Notes

- “Signed petition to offer Anthropology 158, “Race Problems”,” Black History at the University of Idaho, https://www.lib.uidaho.edu/blackhistory/items/ug13_251_003.html. ↩

- Helene Whitson, “STRIKE!…Concerning the 1968-69 Strike at San Francisco State College.” ↩

- “Memorandum regarding petitions for two new courses,” Black History at the University of Idaho, https://www.lib.uidaho.edu/blackhistory/items/ug13_251_002.html. ↩

- “Memorandum regarding petitions for “Negro History” course,” Black History at the University of Idaho, https://www.lib.uidaho.edu/blackhistory/items/ug13_251_005.html. ↩

- “Correspondence regarding petitions for Anthropology 158 and Negro History,” Black History at the University of Idaho, https://www.lib.uidaho.edu/blackhistory/items/ug13_251_001.html. ↩

- “Correspondence regarding “Proposal for a course to be entitled ‘The Negro in American History’,” Black History at the University of Idaho, https://www.lib.uidaho.edu/blackhistory/items/r96.html. ↩

- “Department of History Minutes,” Black History at the University of Idaho, https://www.lib.uidaho.edu/blackhistory/items/mg368_f60_002.html. ↩

- Michael Wickline, “University of Idaho Prof Spent 25 Years ‘Civilizing the White Man’ Jack L. Davis, who Started UI’s Indian Literature Course, Retires at Age 56,” _Lewiston Morning Tribune, _February 10, 1992, https://lmtribune.com/northwest/university-of-idaho-prof-spent-25-years-civilizing-the-white-man-jack-l-davis-who/article_d38b6856-3ddf-5dac-88f0-11c9ad408be6.html. ↩

- “Memorandum titled, “Funds for Black Literature”,” Black History at the University of Idaho, https://www.lib.uidaho.edu/blackhistory/items/r139.html. ↩

- “Memorandum titled, “Apportionment of funds for Negro History Course”,” Black History at the University of Idaho, https://www.lib.uidaho.edu/blackhistory/items/r145.html. ↩

- “Memorandum titled, “Funds for Black Literature (English 327)”,” Black History at the University of Idaho, https://www.lib.uidaho.edu/blackhistory/items/r144.html. ↩

- “Memorandum regarding Black Studies funds,” Black History at the University of Idaho, https://www.lib.uidaho.edu/blackhistory/items/h16.html. ↩

- “Correspondence with Dr. Sorenson regarding available courses related to Black history,” Black History at the University of Idaho, https://www.lib.uidaho.edu/blackhistory/items/h23.html. ↩

- “University of Idaho Class roster for “Negro in America” history course,” Black History at the University of Idaho, https://www.lib.uidaho.edu/blackhistory/items/r175.html. ↩

- “Black Studies,” Encyclopedia.com, 2019, https://www.encyclopedia.com/history/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/black-studies. ↩

- “Memorandum titled “Black History on a ‘white platter,'” Black History at the University of Idaho, https://www.lib.uidaho.edu/blackhistory/items/r149.html. ↩