Black Cultural Center/Student Living

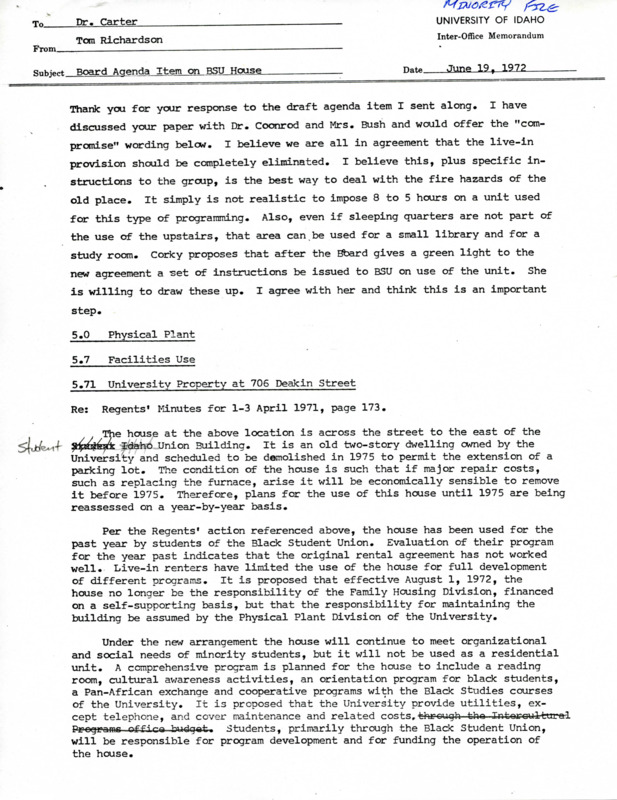

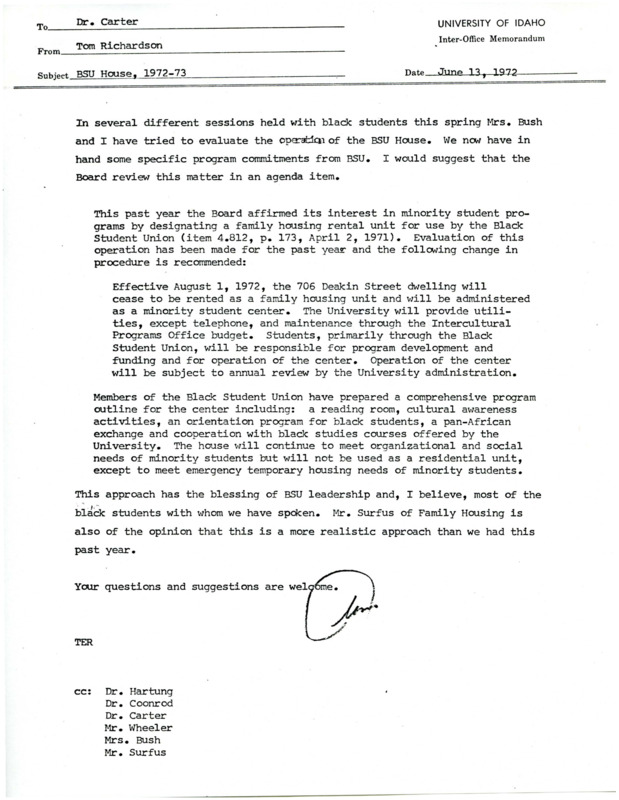

In a memorandum from June 19, 1972, Thomas E. Richardson, Vice President of the University, wrote to Dr. Sherman Carter saying that the original rental agreement the University had with the BSU had not worked out well. He stated that the main reason was that the BSU was limiting “…the use of the house for full development of different programs” (Richardson 1972).1 Due to this issue, Richardson noted that the live-in provision of the house, wherein BSU members had been staying there, was to be revoked and that the house was to be placed under the responsibility of the Physical Plant Division of the University. Under this new agreement, the BSU was still able to utilize the house, but the BSU members were not allowed to use it as a dormitory or office for its members. In a memorandum in that same summer, Richardson would also note that the BSU house would change from a family housing unit rental to a Minority Students Center, operated by the BSU.2

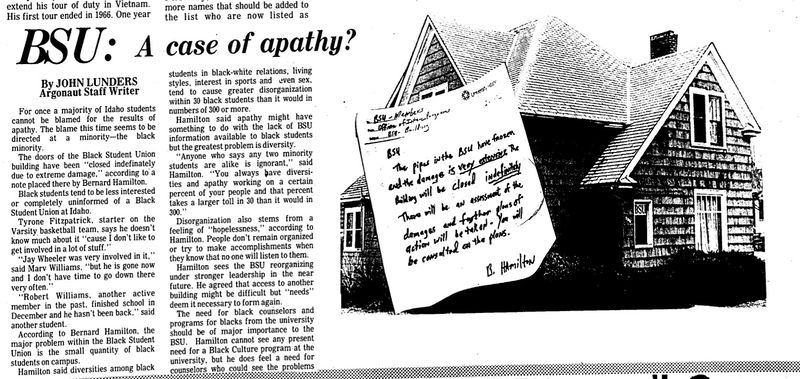

The BSU would remain in the College Master’s house as the Minority Student Center until early 1973, when a freezing winter would blow into Moscow and freeze the piping, doing substantial damage to the property. The damage was so extensive that the building was closed indefinitely, leaving the BSU without a home from which it could operate. Instead of renovating the building, the University would later choose to demolish it with several others in the area.

Around this time it also seems that the BSU had become less active compared to its start in 1971, as noted by an Argonaut article produced in 1973. The Argonaut article titled “BSU: A case of Apathy?” reported on the indefinite closing of the house, but states that “Black students tend to be less interested or completely uninformed of a Black Student Union at Idaho.”3 Bernard Hamilton, a counselor for the BSU in 1973, notes that while this may be the case, the main pressing issues were the lack of a Black student population on campus and a lack of diversity. Whatever the case may have been at the time, it seems that the BSU did not have as much of an outreach on campus as it had initially desired.

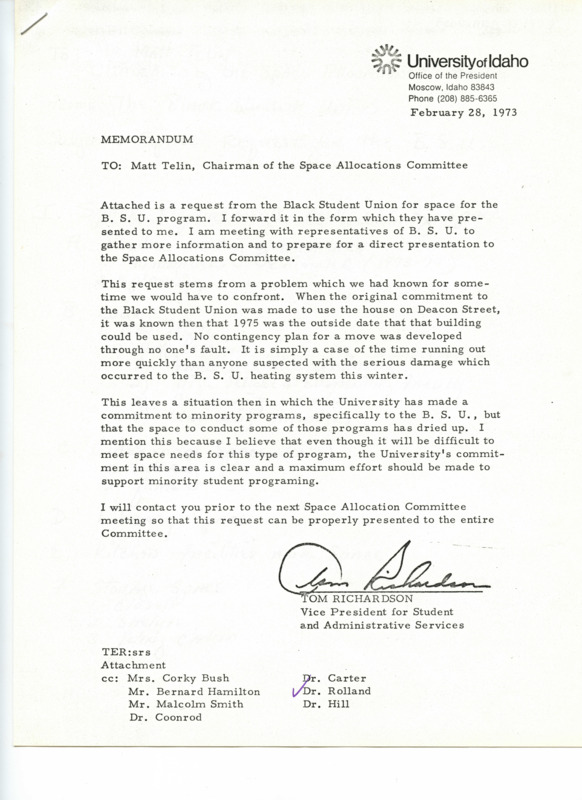

Once the BSU had essentially been kicked out of the College Master’s House, they were in close contact with Vice President Richardson in regard to finding a new home for the organization. Richardson connected the BSU to Matt Telin, the Chairman of the Space Allocations Committee, sending their space request to him in a memorandum shortly after the closing of the College Master’s House. Within the memorandum, Richardson notes that the space the BSU had been allocated was known to not likely last beyond 1975, but the sudden deterioration of the building was unexpected. Richardson also voiced his support for the BSU later in the memorandum, stating that “I mention this because I believe that even though it will be difficult to meet space needs for this type of program, the University’s commitment in this area is clear and a maximum effort should be made to support minority student programming.”4 The BSU would manage to relocate to the Canterbury House, Episcopal Student Center where it would remain under a semi-permanent arrangement.

With a space safely secured, the BSU was able to reopen and begin its operation again on campus. Though there is not much remaining documentation to show whether 1973 was eventful for BSU, it is clear that 1974 was eventful, with the BSU publishing a communique to the University administration. The “Communique from the Black Student Union” is a crucial document in the BSU’s history and outlines several key issues that the BSU (and Black students) faced on campus and the changes needed to improve the campus. Within the document, the BSU listed several accounts of racist activity on campus, with the two biggest incidents being the conflict between Black students and the Dormitory Administration on campus, and an incident regarding a radio personality employed by the University.

Notes

- “Memorandum regarding “Board Agenda Item on BSU House”,” Black History at the University of Idaho, https://www.lib.uidaho.edu/blackhistory/items/h13_105.html. ↩

- “Memorandum regarding “BSU House, 1972-1973”,” Black History at the University of Idaho, https://www.lib.uidaho.edu/blackhistory/items/h13_107.html. ↩

- “BSU House Closes Indefinitely,” Black History at the University of Idaho, https://www.lib.uidaho.edu/blackhistory/items/arg_1973-01-23_p01.html. ↩

- “Memorandum and attached request regarding space for the Black Student Union,” Black History at the University of Idaho, https://www.lib.uidaho.edu/blackhistory/items/spaceallocation.html. ↩