Black Student Union

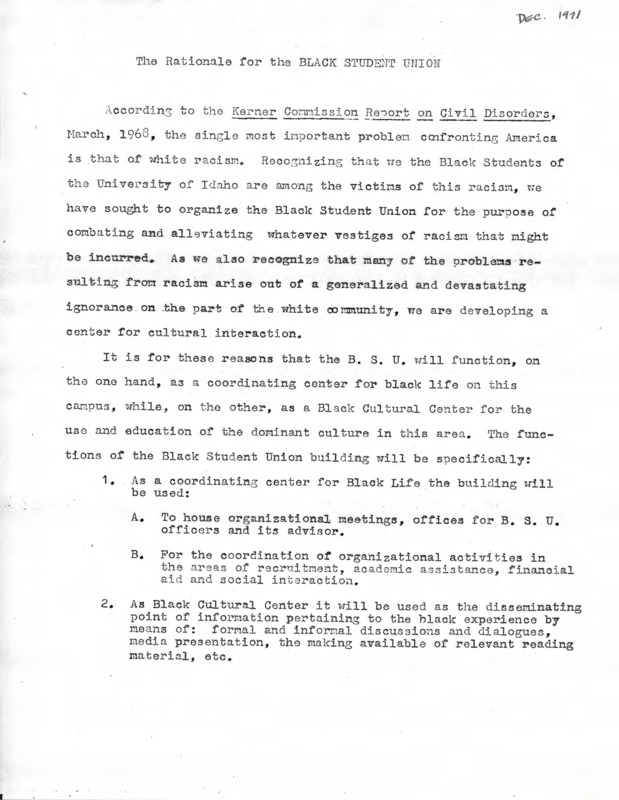

The criticisms and push for inclusivity at the University of Idaho were in large part due to the efforts of the Black student population on campus, even though it was initially much smaller than its current numbers. The Black student population during the late 1960s and early 1970s was almost entirely composed of Black student-athletes who had come to the University of Idaho seeking growth. These Black student-athletes pioneered the origins of the Black Student Union (BSU) in 1971 when they joined together and drafted the “Rationale for the Black Student Union.” This document, though brief, gives vital information into the design of what these Black student-athletes on campus at the time wanted to accomplish, with their main goals being to advocate the importance of Black culture and combat racism and ignorance by creating a center for cultural interaction.1

Looking at one of the BSU’s goals, cultural centers at universities have continuously been at the forefront for many students of color across the United States. The most notable beginning of the demands for Black cultural centers is noted as having been around the 1960s and 1970s, during the Black Student Movement of the time. In the book titled Culture Centers in Higher Education, by Lori D. Patton, it is observed that many Black students demands for Black cultural centers were intertwined with the idea of seeing Black culture in higher academia. Patton notes that “in essence they wanted to see their culture recognized in academics (curriculum and faculty), social life (student activities, residential life), and administrative affairs (financial aid, admissions).2

Following this, Patton also highlights that these demands where fought to make Black students’ campus environment more conducive, cultural centers were sought out by Black students who (after the establishment of centers on campuses) noted that cultural centers acted as a “Home away from Home.” And while the perception of these cultural centers at Predominantly White Institutions is that of a segregation from White students, Black cultural centers in actuality have served as learning spaces for all students. Many Black studies programs have started at these cultural centers with the intention of helping to better educate White persons on campus about Black culture and history. As such, these centers have not only served as safe spaces for Black students on campuses, but also as the focal points of Black student activism on campus that have sought to increase their presence in higher academia.

With this context given in relation to one of the BSU’s overall goals, the original six founders of the Black Student Union were all Black student-athletes, and those six Black student-athletes were Malcolm Smith (President of the BSU), Adrian Prince (Treasurer of the BSU), Jesse Craig, Jay Wheeler, Loren Dantzler, and Robert Lee Williams.3

Malcolm Smith was the first President of the BSU and came to the University of Idaho as a junior transfer from Chicago, Illinois, to play as a running back on the Vandals football team. Adrian Prince, also known as Adrian “The Prince,” was the first Treasurer of the BSU and came from Saginaw, Michigan, in 1967, looking to play on the Vandals basketball team. Jesse Craig came from Los Angeles, California, and was recruited by the University of Idaho primarily for the Vandals football team. Jay Wheeler was one of the more outspoken members of the original six, competing on the track-and-field team. He hosted a radio show and wrote several editorial pieces in the Argonaut. Loren Dantzler came to the University as a junior transfer from San Diego in 1970 to play baseball. And finally, Robert Lee Williams was recruited by the University of Idaho to play as a running back and receiver for the Vandals football team.

These BSU members, again being Black student-athletes, undertook the process of establishing a Black student union by themselves and without support from senior leadership at the University. And while they later did receive some support from the University, the initiative needed on the part of senior leadership would not be present, and the relationship between these two entities (BSU and senior leadership) would crumble.

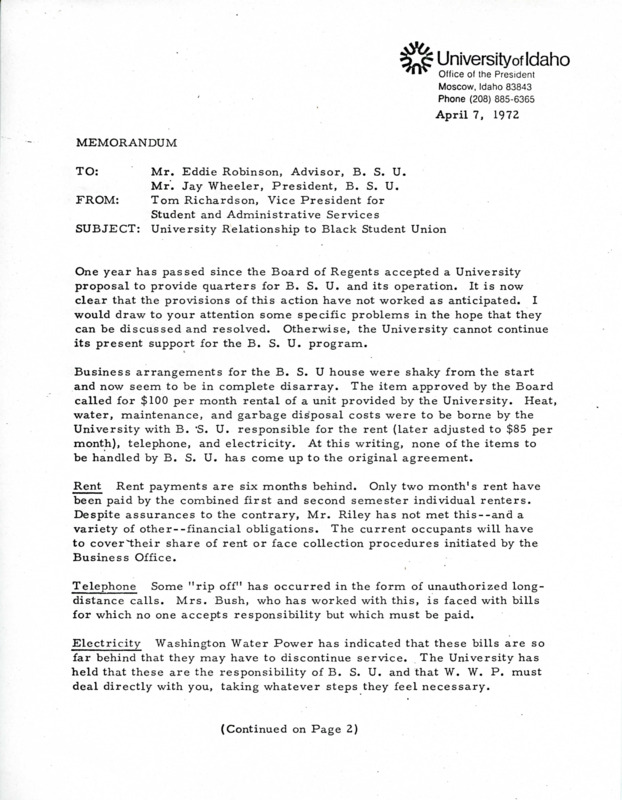

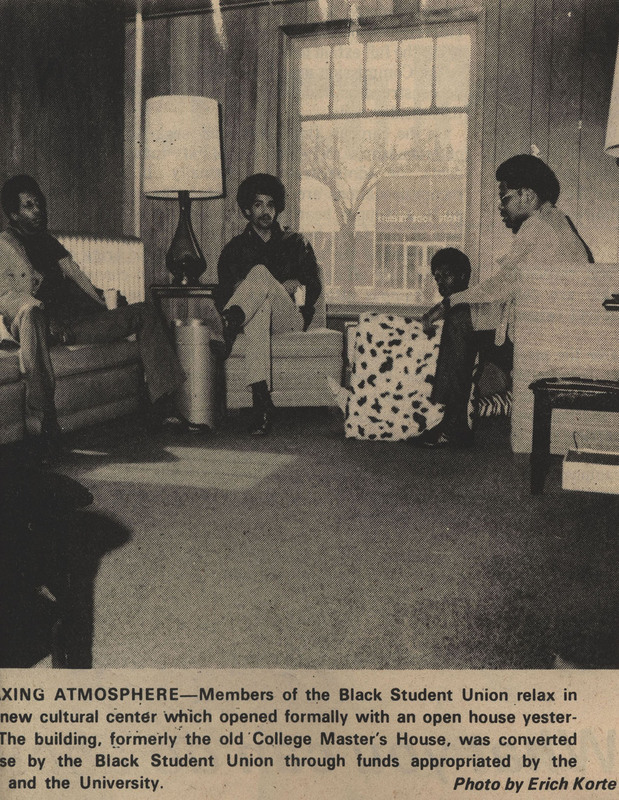

One of the major points brought up within “Rationale for the Black Student Union” was the need for a safe space in which Black students could come together with one another and engage in an inclusive cultural exchange. The BSU would gain a place of its own when it moved into the College Master’s House at 706 Deakin Ave, which sat just across the street from the Student Union Building.4 With the garnering of a space, the BSU was able to formally open its doors to the public in 1971 and act as a place for Black students to congregate with one another. It must be noted that the original six founders of the BSU had not been given the building free of charge and had instead entered into a contract with the University saying that they would pay monthly installments on it, which would become an issue for the BSU later.5 However, at this point in time, the BSU’s biggest issue was funding, as it was a brand new student organization that was not under the direct control of the University.

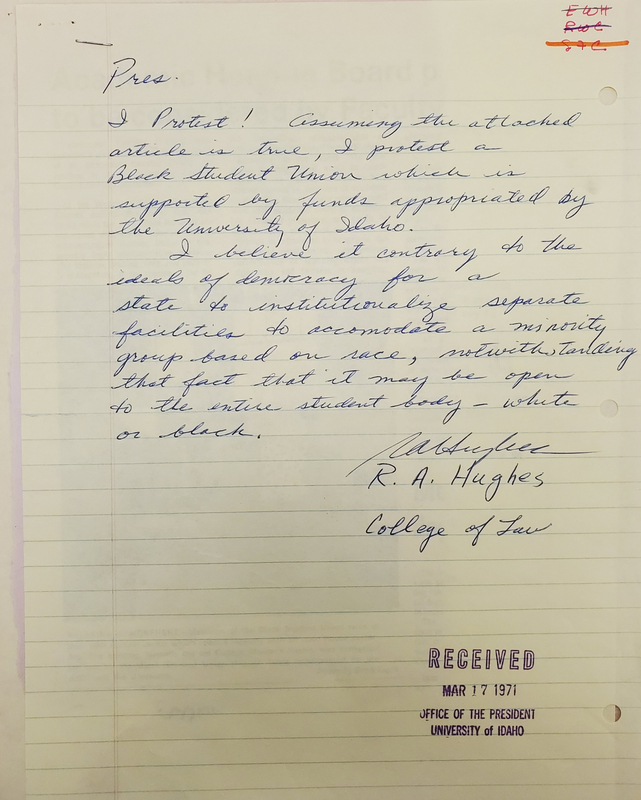

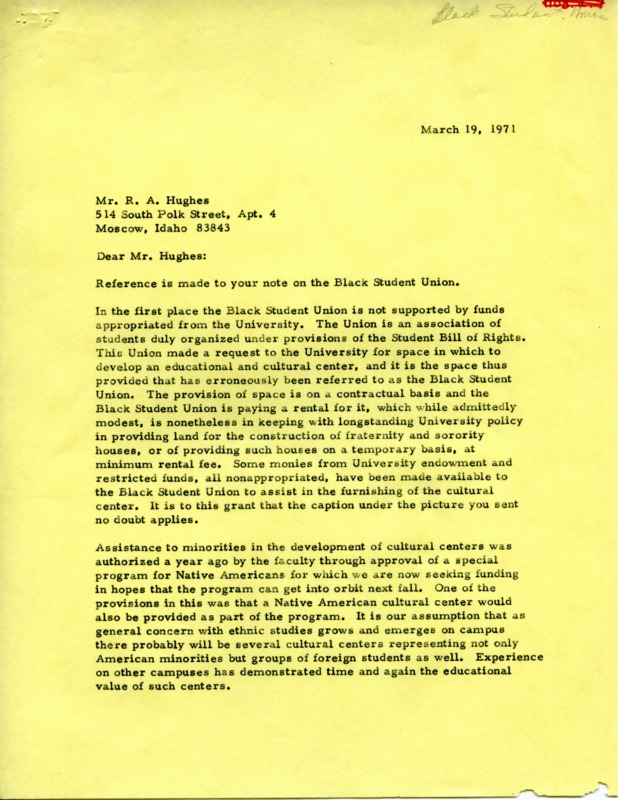

The funding of the BSU became such an issue that faculty members at the University voiced their opinions to President Hartung in their own letters. One such letter from Professor R. A. Hughes pushed back against the requested funds from the University, arguing that he believed “… it contrary to the ideals of democracy for a state to institutionalize separate facilities to accommodate a minority group based on race.”6 President Hartung would respond to Professor Hughes with a letter of his own, stating that

This Union made a request to the University for space in which to develop an educational and cultural center, and it is the space this provided that has erroneously been referred to as the Black Student Union. The provision of space is on a contractual basis and the Black Student Union is paying rental for it, which while admittedly is modest, is nonetheless in keeping with longstanding University policy in providing land for construction of fraternity and sorority houses, or of providing such houses on a temporary basis, at minimum rental fee.7

President Hartung would end this letter by simply stating that while the BSU was renting the house contractually from the University, the University was “…not providing continuing support for the organization called the Black Student Union” (Hartung 1971). The contractual nature of the relationship between the BSU and the University would be one of the many issues that would lead to the reduced presence of the BSU on campus.

During its time at the College Master’s House, the BSU held several open houses and made the general public well aware of the new student organization. There were several pieces written in the Argonaut to showcase the new BSU, with several pieces being written by Jay Wheeler to help promote a Black culture on campus.8

Notes

- “The Rationale for the Black Student Union,” Black History at the University of Idaho, https://www.lib.uidaho.edu/blackhistory/items/h13_115.html. ↩

- Lori Patton, Culture Centers in Higher Education: Perspectives on Identity, Theory, and Practice, (Sterling: Stylus, 2010), 64-65. ↩

- “A History of the Black Student Union,” Black History at the University of Idaho, https://www.lib.uidaho.edu/blackhistory/features/bsu.html. ↩

- “College Master’s House,” Black History at the University of Idaho, https://www.lib.uidaho.edu/blackhistory/items/pg1_003-21-zoom.html. ↩

- “Memorandum regarding “University relationship to Black Student Union”,” Black History at the University of Idaho, https://www.lib.uidaho.edu/blackhistory/items/h13_110.html. ↩

- “Letter Sent to President Hartung,” Black History at the University of Idaho, https://www.lib.uidaho.edu/blackhistory/items/against-bsu_1971-03-17.html. ↩

- “Correspondence regarding the Black Student Union funds,” Black History at the University of Idaho, https://www.lib.uidaho.edu/blackhistory/items/h13_145.html. ↩

- “Black Cultural Center – Interior,” Black History at the University of Idaho, https://www.lib.uidaho.edu/blackhistory/items/arg-1971-03-17_p005.html. ↩