Racial Harassment

Analyzing the communique, the first issue discussed is the conflict between Black students and the Dormitory Administration, the BSU provided an example saying that “White Dormitory Administration culturally forcing Black students to accept White Dietary Habits (that White students won’t even accept), and when Black students protest they are fined and penalized.”1 This incident is interesting as it highlights a smaller employment of systemic racism within the University at the time that did target the Black student population. An added difficulty for these Black students was that they were confined to on-campus living.

The second major incident recorded in the document was the employment of a radio host to a federally funded radio station that wore Ku Klux Klan robes and who the BSU noted as being a member of the Ku Klux Klan. This incident was a more open and recognizable sign of racism on campus and was a bigger issue as this individual was also a security guard for the University and patrolled the dormitory where Black students had to live. These incidents of racism showcased that the University environment of 1974 was not as accepting towards students of color as it may have painted itself to be, which in turn forced the BSU to make a list of ten demands to establish a more secure place for Black students on campus.

This incident was important, not only as a security guard for the University was a member of the KKK, but also because North Idaho is an area known for its dark history with hate groups, especially the Aryan Nations. In 1973, the Aryan Nations had established a compound in Hayden, Idaho, only an hour and 40 minutes from the University. A well-known and documented hate group, they persisted in the North Idaho area until the 2000s, when they were kicked out of the region through legal action and bankruptcy. However, at their peak, they had a strong grip over the area. They were even declared a “terrorist threat” by the FBI in 2001, and they allied themselves closely with KKK groups in the area.2 With this given context, there is a greater insight into why the Black students on campus felt afraid and betrayed by the senior administration of the University. With a known member of the KKK on campus, someone who openly supported the KKK, the direct nature of the BSU’s message to the University certainly made sense.

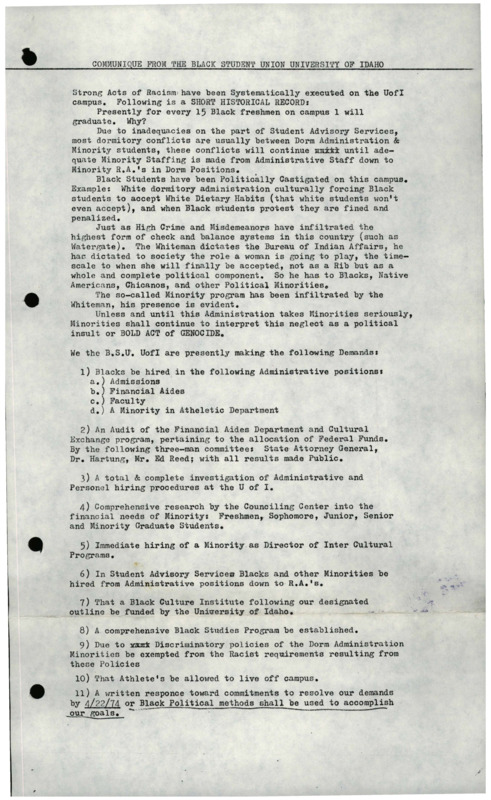

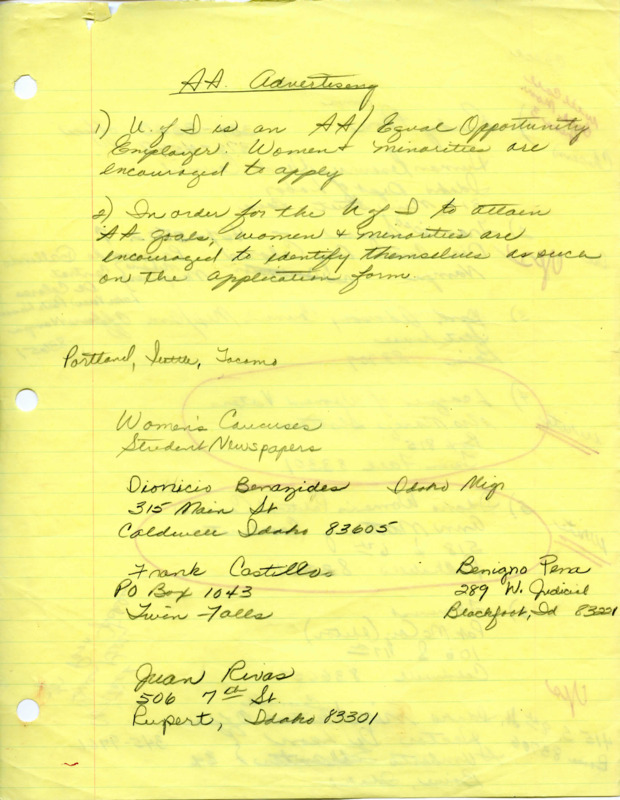

The list of ten demands included in the document was as follows: (1) the hiring of more Black faculty in Admissions, Financial Aid, Faculty, and the Athletics Department; (2) an audit of the Financial Aids Department and Cultural Exchange program to check the allocation of federal funds under a three-man committee (Dr. Hartung, Ed Reed, and the State Attorney General); (3) an investigation into the hiring procedures at U of I; (4) research into the financial needs of minority undergraduate and graduate students; (5) immediate hiring of a minority as the Director of the Inter-Cultural Programs; (6) hiring of Black faculty in the Student Advisory Services; (7) the implementation of a Black Cultural Institute; (8) the establishment of a comprehensive Black Studies Program; (9) minorities being excluded from discriminatory policies of the Dorm Administration; and (10) the allowance of off-campus living for Black athletes.

These demands indicate the increased activity of the BSU on campus and also address the BSU’s desire for change at a much higher level within University management. This list of demands indicates that the BSU felt the University was not as inclusive as senior leadership may have made it out to be, but this can also be noticed in the language used within the document. An example of this can be seen later in the document where the BSU begins to address the Ku Klux Klan incident on campus. They state:

In these times of 1974 Black Students can no longer stand by and permit an all White Administration and [its] White Directors to Determine the Destiny of Black Students and here again White Administrators attempting to conduct a Black Studies Department with a White Administrator Employed to the task. Just as men can longer speak for women, Whites Can No Longer Think for Black People.3

This type of speech indicates that the BSU was tired of the current senior leadership and the lack of policy being directed at fixing the uniform nature of the 1974 White University campus. This document’s speech and its public release no doubt put greater pressure on senior leadership at the University to act. To further ensure that something would be done, the document also includes that if nothing is done, the BSU will employ Black political methods to accomplish their goals, which could have meant anything from campus sit-ins to protests. The BSU was able to effectively utilize this document as President Hartung responded to the BSU by their deadline of April 22 and thoroughly discussed the demands raised.

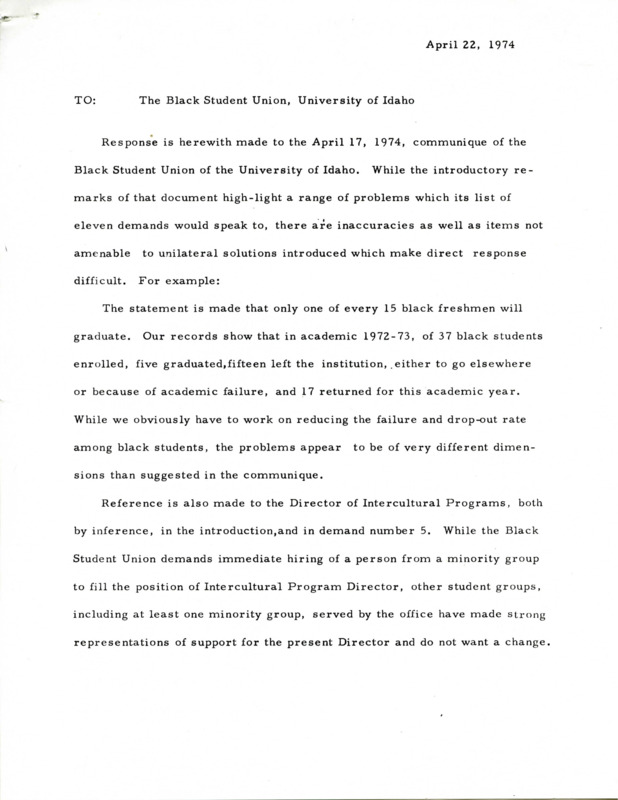

Taking a look at the response provided by President Hartung and the further response of other faculty members at the University, administration and faculty seem to have wanted to work with the BSU, for the most part. In his six-page letter to the BSU, Hartung answers the demands listed by the BSU to the best of his ability and he does a fairly good job at it. At the beginning of his letter, he mentions that in the 1972-1973 school year, 37 Black students had enrolled and attended the University. Broken down further, five had enrolled, 15 had left, and 17 had returned for the academic year.4 This provides valuable insight as it showcases that while the Black student population on campus at the time was small, it had grown since the first wave of Black student-athletes had been enrolled.

The next point discussed was the BSU’s fifth demand of hiring a minority as the Director of the Intercultural Programs, which Hartung says cannot be unilaterally agreed upon as the University has had a hard time hiring Black faculty and the current Director is liked by other minority student groups on campus. The two other high notes for the BSU in Hartung’s response are that the on-campus living situation would be resolved in the next school year, allowing Black student-athletes to live off-campus and that the University would welcome an audit if conducted by the Idaho Commission on Human Rights. The University also agreed to the organization of a Juntura committee to oversee the implementation of a Minority Students Program that would aid minority students academically on campus.

However, President Hartung in turn dismisses other points made by the BSU concerning the hiring of more Black faculty, having a comprehensive Black Studies program, and implementing a Black Cultural Center. These three areas are dismissed by Hartung for two reasons: the lack of a diverse population in North Idaho, and the limited financial resources of the University. This is better explained by Hartung, who states,

The University is located from large, diversified Black populations from which it can attract students and on which it can depend for support for any on-going Black Cultural Institutes or programs. In other words, while we must and will continue to enroll and assist Black students, primary obligation to the people of Idaho, the taxpayers who largely support the institution, suggest the University must also address itself increasingly to a vast number of proliferating state needs.5

The argument made by Hartung does give valid reasoning as to the difficulties the University had with recruiting Black students and faculty, as well as why there were not enough readily available funds for new programs. Nevertheless, the University still appeared to have continued funds for expanding international student recruitment, the Athletics Department, and other strategic priorities.

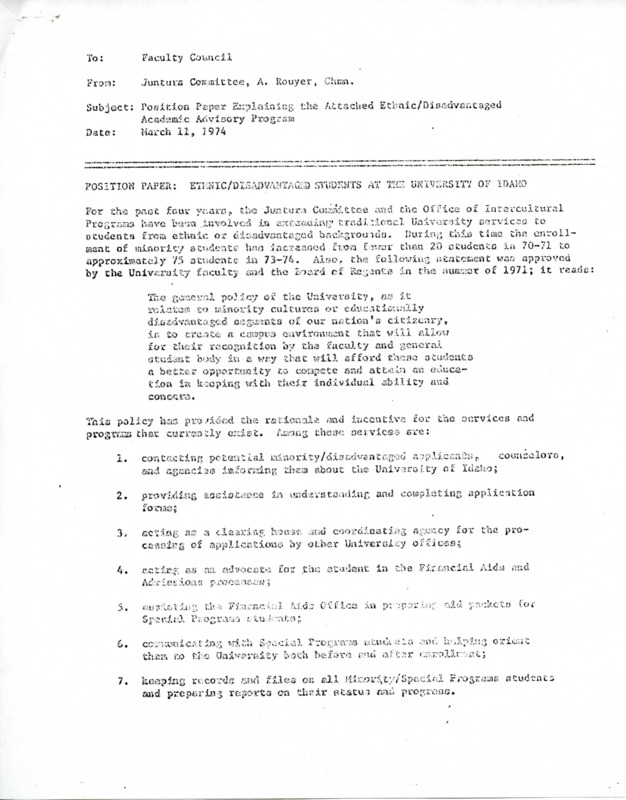

Although the University decided against instituting the more major changes demanded by the BSU, there was progress made within the Juntura committee toward setting up the Minority Students Program. Several memorandums were sent that initially set up the program, naming specific courses and positions within it and further detailing the plan to institute it.6 Charles A. Ramsey II would be the first director called to the position, helping to build it into an organization that would have more say on campus. It is clear that this program, out of all proposed by the BSU in 1974, saw the most success, as documentation exhibits that it saw continued development past the BSU’s departure and into the 1980s.

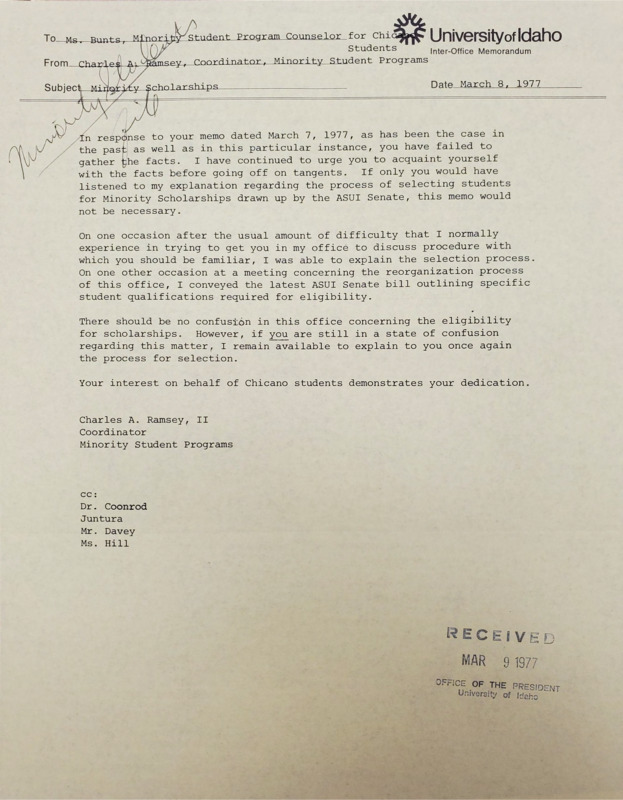

The growth of the program can be seen in the 1976 Capsule Report written up by Ramsey and delivered to the Juntura Committee. From the 1974-1975 school year to the 1975-1976 school year, the Minority Students Program increased from a budget of just under $20,000 to a budget of just above $31,000.7 The increase noted here shows that the program continued to grow and was able to secure more funding from the University, implying that the University did see this program as necessary and important. This is not to say that it saw no issues, as memorandums between Ramsey and other faculty members indicate that the program still had a difficult time in both publicity and organization.8

The program was further reorganized when Ramsey resigned in 1977 and, due to this, the Juntura committee decided it would be best to hire three minority education specialists (Chicano, Native American, and Black) instead of one director.9 Continued support of this progress showcases that the University did place importance on its students of color, but that it did not feel necessary to work with each group on a more personalized level. And though this program did work successfully for the University and its students of color, the other programs the BSU wanted were deemed unessential at the time.

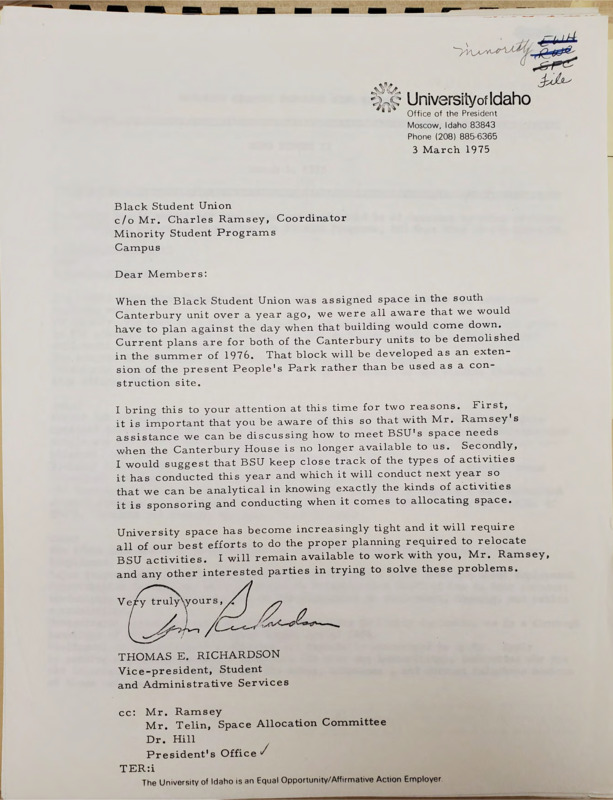

These issues between the Black student population and the senior leadership at the University concerning increased inclusivity would remain unchanged for several decades and locked behind University bureaucratic red tape and a lack of initiative on senior leadership’s part. And as for the BSU in the 1970s, this would be their last major activity; in 1975, they once again lost access to a space and had to depart from the Canterbury Center. The University demolished the building in 1976 to make way for People’s Park, severely limiting the ability of the BSU to operate on campus.10

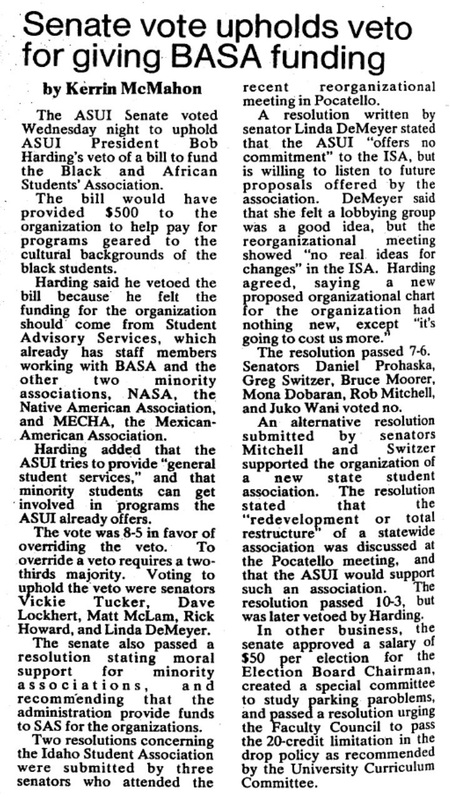

The BSU, without a space secured, underwent organizational changes in the late 1970s and the early 1980s, rebranding themselves as the Black and African Student Association (BASA).11 This closing of a rather active period of the University of Idaho BSU could be compared to that of a closing door, with not much progress being made in the way of furthering Black students and faculty at the University. Despite this inactivity, the push for a more inclusive experience at the University of Idaho would be reignited in the 2000s with the revival of the BSU presence on campus.

Notes

- “Communique from the Black Student Union, University of Idaho,” Black History at the University of Idaho, https://www.lib.uidaho.edu/blackhistory/items/ug074-26.html. ↩

- Threat of Terrorism to the United States, Before the Committees Appropriations, Armed Services, and Select Committee on Intelligence, 2001, (Louis J. Freeh, Director, Federal Bureau of Investigation). ↩

- “Communique from the Black Student Union, University of Idaho.” ↩

- “Response to the Communique from the Black Student Union,” Black History at the University of Idaho, https://www.lib.uidaho.edu/blackhistory/items/ha144.html. ↩

- “Response to the Communique from the Black Student Union.” ↩

- “Memorandum regarding “Position Paper Explaining the Attached Ethnic Disadvantages Academic Advisory Program”,” Black History at the University of Idaho, https://www.lib.uidaho.edu/blackhistory/items/ha193.html. ↩

- “Capsule report on the Minority Student Programs to the Juntura Committee,” Black History at the University of Idaho, https://www.lib.uidaho.edu/blackhistory/items/h79.html. ↩

- “Memorandum from Charles A. Ramsey to Socorro Bunts regarding minority scholarships,” Black History at the University of Idaho, https://www.lib.uidaho.edu/blackhistory/items/h74.html. ↩

- “Memorandum regarding the Minority Student Programs,” Black History at the University of Idaho, https://www.lib.uidaho.edu/blackhistory/items/h54.html. ↩

- “Correspondence regarding the Black Student Union,” Black History at the University of Idaho, https://www.lib.uidaho.edu/blackhistory/items/ha70.html. ↩

- “Senate Veto on BASA Funding,” Black History at the University of Idaho, https://www.lib.uidaho.edu/blackhistory/items/arg_1978-04-14.html. ↩